The word ego is English, as you know. In Sanskrit the word that conveys the sense of ego is alaya. In Tibetan it is dak, which means “I” or “thisness.”

As we begin to discuss the meaning of ego, we are not doing so from the point of view of Jungians, Freudians, or other psychological approaches, but we are talking about ego in an exclusively Buddhist way.

The Buddhist view of ego is that it is a nuisance, an obstacle, whereas in Occidental cultures we say you should have a better ego, so that you can function in your business world and so forth. On top of that, we might even say that you have a divine ego, which might take care of your spirituality, whatever that is.

In Buddhism, whether we talk about ego, atman, dak, or alaya, all those terms point to basic fixation. You are holding onto a certain particular thing, and you do not want to let go of it. You are hanging on to something, and that something is questionable.

But what is that something?

That something is very embarrassing. Maybe I shouldn’t discuss it, for the sake of saving everybody’s face, but maybe I should, for the sake of this particular course.

In talking about Buddhism, I’m afraid I have to be savage. It is very embarrassing to discuss this. To begin with, this something is something that we do not want to face. We are disgusted with it, with what it is. (We are talking about ourselves, by the way; we are not talking about “them.”) Because of this something, we feel that by successive, continuing deceptions of all kinds we may finally be able to win some kind of war. With this something, we do not want to actually smile but just to give the pretense of a smile.

On the whole, we have a private part, one singular private part that we do not want reveal to others—goodness no! Certainly we do not want to reveal it to ourselves. It even embarrasses us in our dreams, in our sleep. While we are sitting on the toilet or having a nice shower we are still embarrassed by ourselves constantly. That something makes us proclaim our privacy: “I need privacy. Can you just leave me alone for a minute? I need to think about something. I have to read a book. Can you leave me alone for just a minute? Oh, how nice to see you! Good-bye!”

All those games that we go through are actually because we want to percolate our ego, our privacy problem, which is very smelly mustard brewing all the time. But at the same time, such games help us sustain our “whatever it is.” So we have a double game going on: a game going on with others and a game going with ourselves. That is what is called ego.

Here and there we have various experiences of embarrassment and hesitation, but we really do not want anybody to expose that. We would like to keep that extraordinarily secret, keep it within us all the time. So we always try to hold back, even from ourselves. Sometimes you find it very hard to look at yourself in the mirror and cheer yourself up. You try to make a funny face for yourself, but it doesn’t seem to be at all funny. It is depressing, embarrassing, revealing everything on your face. The mirror throws things back in your face, and you are embarrassed all over again.

There is that private part, but this private part is not the conventional idea of private parts. The conventional idea of private parts is that you do not want to expose your body: your genitals, your tits, your funny body with its freckles and pimples and hairs growing all over. Embarrassment about such things is breaking down already in so-called American culture. There are nudist colonies, and husbands and wives no longer feel embarrassed undressing in front of their spouse. If they did, it would be regarded as old-fashioned.

However, exposing this private part is not so much about taking off your clothes. There is more to it than taking off your clothes. The idea of breakthrough, of acknowledging one’s private part, is actually very subtle. Instead of private parts, there is only one “private part,” a singular thing: it is your own mind!

Our mind is so screwed up and confused, and at the same time it tries to be so tricky all the time, as we know. We try our best to keep it up, and afterward we say it was just a rehearsal, but it doesn’t quite work that way. A further problem with that is that we have no sense of dignity. Therefore, the only thing that can occur in our life—in relation to other people, to our world, and to ourselves—is to be deceptive. That always happens. Every one of us has our own version, our own particular style of keeping secrets of all kinds, which is quite unspeakable. It is utterly shocking.

You might appear to be well groomed, well behaved, such a reasonable person, but behind that whole thing there are loads and loads of garbage that you do not want to throw out. In fact, you want to manufacture more garbage, again and again. You keep producing greater garbage, millions and millions of maggots, and you get high on that. You have maggots in your brain, in your heart, in your stomach, wherever you keep your maggots, which makes you high. Someone has to be honest about this; otherwise, everything goes down the drain.

Spiritual discipline is supposed to keep or to maintain people’s sanity. In this regard, the life example of Milarepa helps us see how we maintain our deception and our embarrassment with ourselves. In the song “Challenge from a Wise Demoness,” a she-demon appears before Milarepa as a precise manifestation of that kind of confusion.

Basically, we want to hold on to our confusion, and we do not want to give in to any messages coming from outside. We let the world be confused, so no one can catch us. We hope people will think we are good persons, reliable persons. We hope they might save us. That approach is a problem, even if you have already begun practicing. For instance, even after Milarepa had been studying with his teacher Marpa for a long time, and he had received all kinds of teachings from Marpa, he still was unable to let go of that embarrassment in him, which we could call “ego.”

The basic constituents of ego are of three simple types: one is passion, the second one is aggression, and the third one is ignorance. Passion means trying to suck things in, to collect things for yourself. Aggression means pushing out or exorcising anything that goes against your particular scheme. Ignorance means ignoring anything that comes up and puts you on the spot, because it is too embarrassing to look into it. These three always operate in our basic ego, and that basic ego takes place all the time. That is what is known as ego fixation, and there is nothing respectable about it.

The renunciation of ego only takes place when somebody in the form of a teacher, guru, master, or friend begins to expose your dirty tricks. Those tricks have not been all that clever; they are known tricks. In two thousand of years of Buddhist practice, throughout the lineage, as far as real practitioners are concerned, everybody in the Buddhist tradition knows all those tricks, including twentieth and twenty-first-century tricks. So there is no way that one could get away with saying, “Don’t you think I’m enlightened?” and have the teacher say, “Sure, go ahead.” Instead, the teacher would say, “It looks like you are freaked out. It looks like you are kidding yourself.”

People may be extraordinarily dedicated to the practice and want to do everything they are told, but at the same time, they have their little schemes going through their heads. They think, “If I do everything as prescribed in my apprenticeship, then one day I will be the ruler myself.” That is what is known as spiritual materialism. Absolutely. Spiritual materialism is about trying to build your ego. You feel great! Fantastic! You may be sh*t, but you still think you are chocolate mousse! But if you want to practice real spirituality, such politeness does not work. You have to be honest and real. If you are sh*t, you are sh*t! You are not really chocolate.

In the “Challenge from a Wise Demoness,” through his encounter with the demoness Milarepa began to realize that he had been deceitful to himself. That is why the demoness was called a “wise” demoness. The situation was wise, so Milarepa began to give in to that situation. In this story, the ghosts that come to Milarepa are not external persons but his own manifestations. The story of the wise demoness represents the fact that you cannot play tricks on situations and convert them into what you want. If you are so speedy that you run into a lamppost, the lamppost could be said to be a wise demoness: a wise lamppost.

The renunciation of ego can only take place if you are willing to give up your own deception. When somebody keeps telling you that you are full of sh*t, you may not believe it; but when you begin to smell your own sh*t, you begin to realize it is the case. You begin to expose your own deception. Then, having exposed your own deception already, there is nothing very much to keep secret. Therefore, you begin to feel pretty sh*tty, and there’s nothing to do about it other than to renounce that deception. It becomes obvious.

At this point, in terms of your relationship with the world, you are the world. There is no such thing as “you” and “outside world” anymore: you are the world. You are the world, you are the streets of the city you are living in. There is no such thing as a division at all. You are what you are. You are the sun and the moon, your watch and your telephone, your bus and your taxi. You are what you are. If you realize who you are, you are the outsider as well as the insider at the same time. So there is no such thing as privacy. Everyone knows what you are doing and who you are, in any case. Although this may sound terribly claustrophobic, it is true. And if you try to find something other than what you are, obviously you have problems.

~

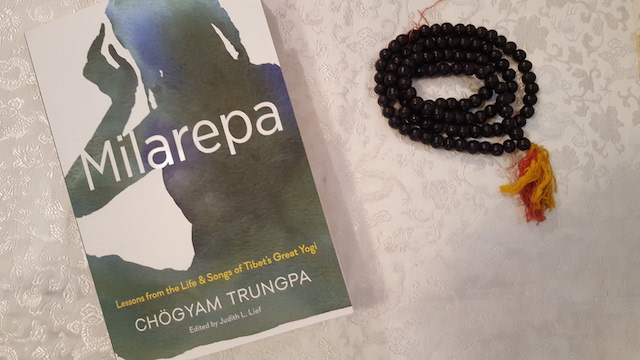

From Milarepa by Chogyam Trungpa, edited by Julith L. Lief, © 2017 by Diana J. Mukpo. Reprinted by arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO. www.shambhala.com

Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche (1939-1987) was the founder of Shambhala Buddhism. Trungpa Rinpoche was the 11th descendent in the line of Trungpa tulkus, important teachers of the Kagyü lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. Renowned for its strong emphasis on meditation practice, the Kagyü lineage is one of the four main schools of Tibetan Buddhism. In addition to being a key teacher within the Kagyü lineage, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche was also trained in the Nyingma tradition, the oldest of the four schools, and was an adherent of the rimay or “non-sectarian” movement within Tibetan Buddhism. The rimay movement aspired to bring together and make available all the valuable teachings of the different schools, free of sectarian rivalry. Throughout his life, Trungpa Rinpoche sought to bring the teachings he had received to the largest possible audience. For a more complete bio, please click here.

~

~

~

Author: Chogyam Trungpa

Image: elephant archives

Editor: Travis May

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 1 comment and reply