In the early 1930s, J.R.R. Tolkien began work on The Hobbit.

Had he taken up the task of penning an academic essay extolling the virtues of courage and self-sacrifice, I doubt we would remember him.

The overwhelming majority of people prefer storytellers to philosophers. Storytellers occupy a special place in society because they perform a sacred function.

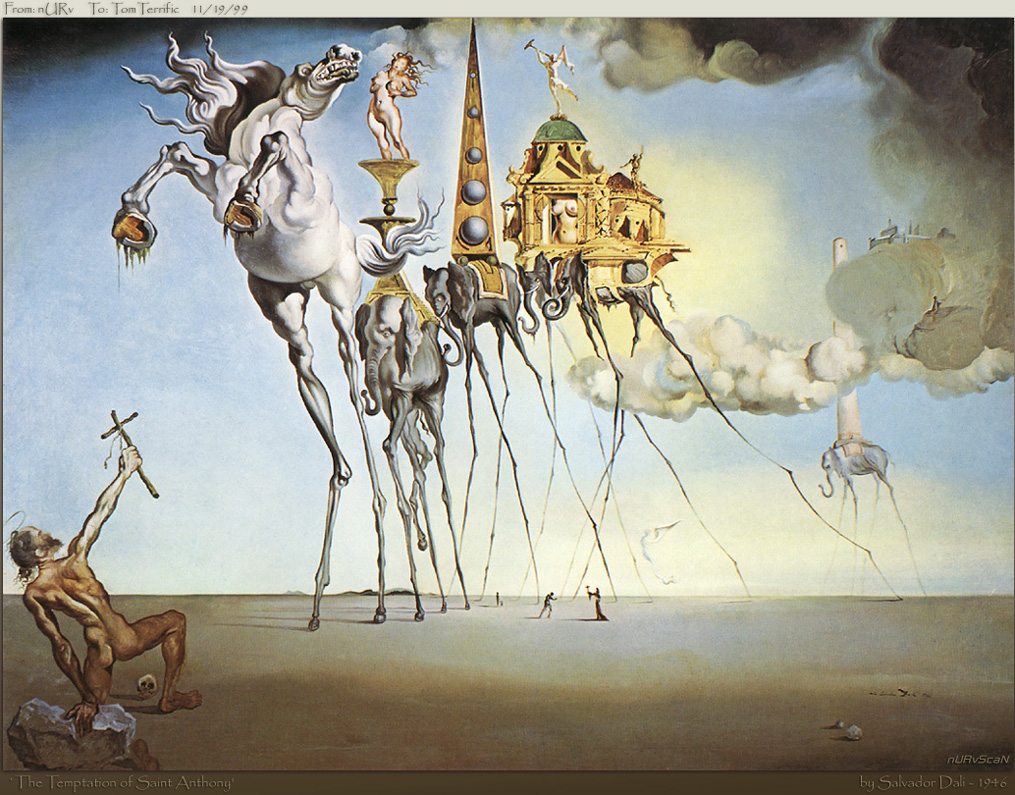

The storyteller’s elevated status in society is owed to their ability to bypass our superficial state of consciousness and arouse those energetic principles embedded deep in the human condition that animate our lives. Storytellers are the keepers and progenitors of our mythology.

Myth is a constant force in human history. Wherever man is found, so too is myth and where there is myth there are storytellers. Myth is a record of humanity’s exploration of the human soul. It contains snapshots of those remarkable moments from the inner story of mankind. Perhaps no one was more aware of this than Carl Jung:

“The coming of consciousness was probably the most tremendous experience of primeval times, for with it a world came into being whose existence no one had suspected before. And God said, ‘Let there be light’ is the projection of that immemorial experience of the separation of consciousness from the unconscious.”

Whereas history and science details the story of the cosmos and our species, mythology tells the remarkable story of humanity’s inner journey. When mythology is mistaken for the former, it devolves into fundamentalism.

The central mythos of the West is compiled in a collection of books known simply as the Bible. The Bible is an anthology. It is a compilation of myths—not a monolithic record of infallible truth-claims, as it is too often thought to be.

A literal reading of the Bible brings you to the unintelligible conclusion that an all-knowing, all-powerful anthropomorphic creator God fashioned a world with which he was so displeased that he had to offer up his son as a blood sacrifice to pacify his own wrath. This is nonsense. And furthermore, it has nothing—and I mean absolutely nothing—to do with the reality of our daily lives.

The Bible did not fall from the sky in its completed form. The books that comprise the Bible were penned over the course of approximately 900 years. Therefore, the books of the Bible were written by many different authors, each of which had their own worldview, interests, and agendas.

As a result, the biblical narrative unfolds on several different levels. In it we see the curiosity of pre-scientific man musing over the origins of life and the cosmos. We see the ruling class advancing their political agenda, and in turn, we see the voice of the oppressed and marginalized pushing back—pressing the issue of social justice. And as the biblical narrative advances, it becomes increasingly concerned with human spirituality.

The Bible records an evolving worldview, which is simply incompatible with the idea that it was dictated to a series of stenographers by an all-knowing god. With every act of divine retribution, flood, exile, every time a new prophet emerges on the scene, and with every utterance of the words, “You have heard it said, but I say unto you,” the Bible ushers in a new vision, a new covenant. The Bible is not the infallible will and testament of a divine monarch. It is a record of humanity’s wrestling with God, as well as an invitation for each successive generation to continue wrestling with the indwelling presence of the divine.

Myth is mankind’s ongoing dialogue with the divine. But the record is not closed. It is our job to continue the dialogue. We have to enter the myth.

Mythology invites us on a journey. “I am looking for someone to share in an adventure,” Gandalf says to Bilbo Baggins. The Hobbit is not a story about an adventure. The Hobbit is an invitation to adventure. Likewise, the Bible does not tell us about God; it invites us to wrestle with God. It invites us onto a path of spiritual practice that leads to union with God, that reunites the mind and body.

To understand myth you must involve yourself in the motif. Myth is a practice that you must immerse yourself in; it is a path that you must walk. When you realize that the path of the central figure (the hero) is presented to you as your way, your truth, and your life because their journey is a metaphor for your journey, the story dissolves into the immediacy of your own adventure. At that point, “the big question,” says Joseph Campbell, “is whether you are going to be able to say a hearty yes to your adventure.” Spiritual practice is what enables us to say yes.

Perhaps the most sophisticated applications of mythology are found in Buddhism and Christian mysticism. In Vajrayana Buddhism, there are meditation practices that enable the individual to enter the mythos for themselves. Practitioners of Buddhist tantra visualize themselves as the deity (yidam), which enables them to awaken to the principles associated with that deity, as well as subtler states of awareness—all of which, in reality, constitute the structure of their being. Through repetition, the practitioner incorporates the attributes associated with the deity into their lived experience, which is what it means to be transformed or, in Christian language, “saved.”

Similarly, Christian mystics practice what is called the Imitation of Christ. They use the power of imagination to identify with the Christ image, which through repeated practice births the image of God into the world, thereby fulfilling the central aim of Christianity.

Exercises like yidam practice and the Imitation of Christ are perhaps the most profound systems of spiritual practice ever developed. They allow the indwelling presence of God to become incarnate; they give birth to Buddha-nature. Their profundity is owed to the union of myth and practice, as well as the fact that one can utilize these systems without buying into the mythology on a literal level. While they may be the most profound expressions of myth, they are certainly not the most common. These practices tend to be reserved for only the most dedicated students.

As I said at the outset, storytelling is humanity’s preferred vehicle of spiritual transmission. The values that define the human experience and the principles that encourage us to pursue a more perfect relationship with each other and the planet are passed on from one generation to the next by storytellers. Practitioners of this art include everyone from Homer to Tolstoy, Tolkien, Rowling, Lucas, and Joseph Campbell. But storytelling also has its place in traditional religion.

Among the world’s major religions, Judaism is unique, in that storytelling is its modus operandi. For many rabbis, like the Baal Shem Tov, storytelling is the preferred method for unveiling the divine. Simply reading Rebbe Nachman’s The Seven Beggars is a spiritual exercise. As you immerse yourself in the story, the principles of the Torah unfold from within you, which is the function of myth. The author of myth is indwelling. When we study myth, we are not studying books. We are using books to study ourselves.

Another good example of spiritual storytelling can be found in groups like Alcoholics Anonymous. In fact, there is a remarkable parallel between 12-Step groups and Jewish storytelling, as Ernest Kurtz demonstrated in his book The Spirituality of Imperfection. Twelve-Step groups owe much of their success to the melding of storytelling in their meetings with the actionable path structure outlined by the 12-Steps.

When skillfully pursued, the study and practice of myth is a spiritual practice because it has the capacity to elicit the experience of transcendence. It has the ability to move us beyond the limited, self-centered world between our ears and connect us with a greater reality, the unconscious wisdom of the body. I will conclude with an excerpt from my book, Finding God in the Body:

“The symbols that populate the world’s great mythologies are born out of the body. Mankind cannot part ways with myth. He can distance himself from organized religion, but not spirituality and myth.

‘Throughout the inhabited world, in all times and under every circumstance, myths have flourished,’ writes Campbell. ‘And they have been the living inspiration of whatever else may have appeared out of the activities of the human body and mind.’

Mythology is rooted in our biology. It is a part of our makeup to the extent that it gives voice to our makeup. Mythology satisfies the desires of our heart without sacrificing the integrity of our intellect. In this sense, mythology occupies the space between fundamentalism and atheism.

Since spirituality is ultimately concerned with embracing and embodying the human condition, and myth is rooted in our very nature, myth is an integral part of the spiritual path.

There is always a dimension of inner space beyond definition and explanation. This is the domain of myth. Mythological symbols mediate the relationship between the unconscious wisdom of the body and the intellect. Myth connects the formless realm of truth and inspiration with our rational mind. Our sacred myths are rooted in the transcendent realm of human experience—those aspects of our humanity that escape plain speech.”

~

Don’t have time to read the article or just prefer a podcast? Listen to episode 10 of the Finding God in the Body Podcast where I talk about the role myth plays in human spirituality. I cover everything from storytelling, to tantra and Christian mysticism, and groups like Alcoholics Anonymous.

~

~

~

~

Author: Benjamin Riggs

Image: Wikiart

Editor: Travis May

Read 0 comments and reply