“I did then what I knew how to do. Now that I know better, I do better.” ~ Maya Angelou

~

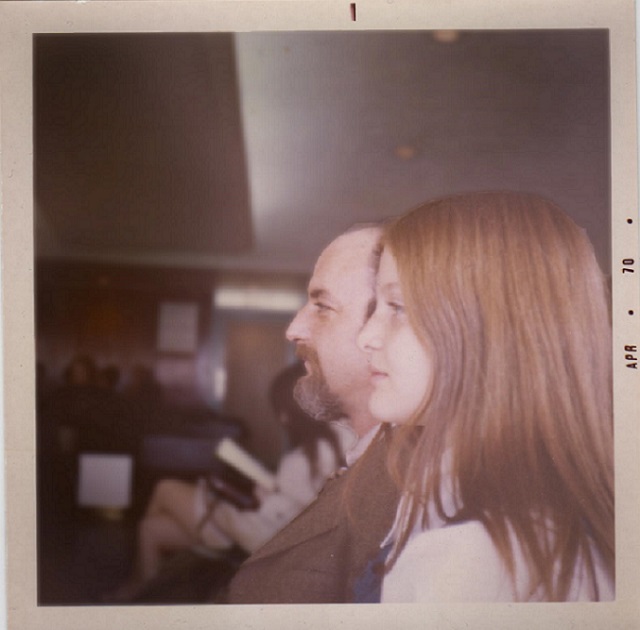

Three years before my dad’s stroke, he told me that he knew he was going to die.

His heart had developed an arrhythmia and he feared a crippling stroke, so he set up a DNR (do not resuscitate). Like a wild animal who knows winter is coming, he began to prepare.

His preparation became my opportunity to face the brick wall between us.

His business manufactured a product that required precise engineering, and that’s what he demanded in all aspects of his life. Perfection.

I was always on a search for how I might be good enough. He flew into a rage when something wasn’t done to his standards. As a child, living with his demands was terrifying. Normal childhood mishaps like spilling juice, making a mess while playing, or refusing to eat something disagreeable were punished with threats, shouting, condemnation, humiliation, forced feeding, and isolation.

He rarely gave without condition. If he made an offer, as soon as I became involved in the excitement of receiving, he’d pull back the gift. I learned to stop asking.

Each incident felt like I’d been hit with a brick. To protect myself, I used these bricks to build a wall of protection.

His intense energy found a healthier outlet in family camping trips and vacations across the United States, Europe, and Israel. These trips filled my senses with nature’s beauty, diverse cultures and cuisines, music and art, and rugged historical and archaeological sites. When he was fun, life was magical.

My dad stood in the way of my dreams as intensely as he followed his own. In my teen years, when doctors couldn’t help me with my digestive issues, I studied diet and nutrition on my own, which led to an interest in naturopathy. Back in the 70s, my dad called naturopathy a quack profession and forbade me from following this course of study. Being 17, under the spell of his chaotic charisma and hoping to find his approval, I swallowed my resentment and backed down.

My parents had divorced when I was 10, and my mom met a better man when I was 19. One Sunday afternoon, I walked into the living room while he read the paper. He put it down, and we had the first of many heart-to-heart talks.

As my soon-to-be stepdad picked up on my buried emotions, my protective wall crumbled. He objectively understood my dad’s behavior in a way I hadn’t. “Your father pulls the wings off flies and enjoys their pain,” he said. For the first time, someone acknowledged my dad’s behavior in a way that freed me from self-blame. There was probably nothing I could do to earn his approval, but now I could see this was his issue, not mine.

As my stepdad and I became closer, he urged me to have a relationship with my dad, even when I didn’t want to. My stepdad understood the pain that drove my dad’s behavior, the pain that would result from his losing a child, and the pain I would experience by separating from my parent. But he wanted me to relate from a place of strength, have my eyes open to the reality of my dad’s behavior, and know what to expect.

Still in college, I was lucky that my stepdad and professors kindly identified my skills and interests and encouraged my studies in philosophical and literary inquiry, horticulture, and writing. In the beautiful Southwest, I also discovered nature photography. I learned that even though my dad could be unkind, the world was filled with people who understood and helped others.

When I earned straight A’s and joined the honors program, I expected my dad to be proud. Instead, he looked at my report card and shouted, “You think you’re so smart. You think you’re smarter than me.” His jealousy crushed me.

As I got older, I realized it was probably a blessing that my dad stood in my way that day, because I found great joy and success in teaching and writing. But for many years, I couldn’t be grateful for the joy and grace that came from pain. Instead, I nurtured a boulder of anger and resentment.

Thankfully, I also learned to meditate to find the peace I craved, which helped me separate his words and actions from who I really am.

The day he told me he was going to die, my dad visited my house to give me three gifts.

He sat at my dining room table and watched me unwrap crystal tumblers and champagne flutes that my parents had received as wedding gifts. Though I knew he was still angry and hurt from the divorce, even 30 years later, those glasses took me back to a time before pain. I knew I’d been born from love.

He also gave me hand-blown paperweights from his extensive collection. Each year, he purchased a box full of hand-blown paperweights and asked his employees to take one during the annual office party. He always invited me to these parties, so I had always taken a paperweight. He didn’t remember, though, so he looked around, puzzled, and asked where I’d gotten all of them! And then he looked at me, smiling, as I opened these intentional gifts.

His last gift was a set of kitchen knives. He showed me how to use the sharpening stone, and told me that the penny tucked in the box meant that even the sharp blades couldn’t sever our connection. It was miraculous that our relationship still existed, and sitting there, I was glad I hadn’t given up.

He giggled with embarrassment and told me I looked pretty. Then he told me I was strong. I’d learned to stand up for myself in part because of him, so his compliment reminded me of painful times. Though I knew by then that he was proud of my professional accomplishments—I had earned my doctorate, taught students from kindergarten to university, and published works in several fields—he told me for the first time.

His words and gestures dislodged some bricks and touched the shattered place inside me in a gentle way I barely remembered, but the boulder of my resentment still sat heavily in my gut. I would have been more touched if he’d encouraged me to get to where I was in my life.

Over the next three years, we spent more time together, and he helped me more than he had in the past. With my mom’s help, I tried to understand his hopes and disappointments better. He had softened a little, and I worked at letting down my guard, but I’d distanced myself emotionally for so long that I still experienced a fear reflex. I needed time to adjust and see if I could trust him.

Three years after he gave me those gifts, he suffered and survived the stroke he feared. For the next three years, he lay mute and immobile, his powerful will struck down by a pea-sized clot created by the struggling rhythms of his heart.

My heart broke for him—a man so forceful and full of life, now unable to participate in life on his own terms.

Maybe it’s selfish, but I’m glad he lived. No longer working long hours and traveling, he was home all the time. He was also disabled and mute, which helped my fear subside. I sat with him, held his hand, rubbed his shoulders, and talked to him about my days and life in general.

I wasn’t sure what he could understand, but he seemed to communicate through facial expressions and body language,. When he got tired of holding hands, he let go. When he was finished eating, he motioned with his hand to stop.

A few weeks after his stroke, an accident almost took my life. I discovered why people who face their own mortality feel deep gratitude for life and want to make amends. Maybe that’s what started happening to my dad. The combination of his disability, the medical challenges from my own near-miss, and my expanded gratitude for life prompted me to re-evaluate my life.

A brush with death showed me there may not be much time left, or there may be a lot. Either way, I felt compelled to refocus my energy on discovering what really gave me joy so I could love every minute of my life in my own big way.

I slowly let go of seeking objective perfection. Instead, I sought perfection in being, which I discovered in the flow of creative experimentation with writing and photography, altered psychic states using hypnosis and meditation, and processing my near-death experience. I earned my health coach certification, studied hypnosis for healing, developed a private coaching practice, started writing books, and delved into nature photography. There was so much more in life to love than naturopathy!

On my dad’s 83rd birthday, I brought my laptop to share some of my nature photos with him. As I showed him each picture, I saw my own joy spread to his face in a large grin. Our eyes locked in a moment of love and acceptance, where I could finally see that he was happy about something that made me happy.

A month later, he died.

I looked through old photos in his attic and found one of him as a child riding a pony—his eyes and smile twinkled with innocence and hope. Seeing him as a happy child triggered a profound sense of compassion. I realized that his challenges with his own mother and father, which I’d only heard about secondhand, had mortally wounded him.

I realized my dad had tried to make the end of his life better than the middle. I can still find issues I wish we’d had time to resolve, and apologies I wish he’d made, but he’d done better. And that’s what people do. We make mistakes, then we do better—until we run out of time.

The boulder in my gut dissolved. I felt love for my dad, less encumbered by the past. In learning to accept him, I could forgive him, and forgive myself for holding on so long.

There are days when I’m not in a state of forgiveness, but I can find my way to compassion. Being witness to my dad’s anger all those years, I’ve concluded that it’s best to find my own joy, gaze with love, and forgive the rocky middle years before death is in sight.

Or better yet, fix the middle part, if possible. Because if we’re not at the end, we’re still in the middle—which means there’s still time.

~

~

Author: Sally Stone

Image: Author’s Own

Editor: Nicole Cameron

Supervising Editor 1: Catherine Monkman

Supervising Editor 2: Catherine Monkman

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply