“I fear not the man who has practiced 10,000 kicks once, but I fear the man who has practiced one kick 10,000 times.” ~ Bruce Lee

.

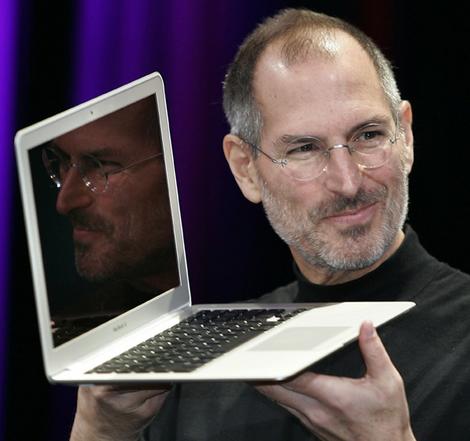

In Steve Jobs’ commencement speech at Stanford University in 2005, he declared, “You’ve got to find what you love.”

He also said he was lucky to have found his passion at an early stage.

He didn’t mention, however, that to become great at something we also need to put in the hours. We must constantly practice our passions if we wish to improve. Jobs’ own life work demonstrated the results of working long, focused hours.

In effect, his words and deeds displayed the “craftsman mindset.”

Follow your passion.

It is a commonly held belief that one is either born with innate talent, like Roger Federer’s grace on a tennis court—or destined for greatness, like Joan of Arc, who helped push the English out of France.

Now, more than ever, the media and self-help gurus are pushing us to discover our passions. This mantra of “finding your passion” is not only overwhelming, but all-consuming—and if we are not careful, it can lead us down a rabbit hole of fruitless searching.

For so many years, I tried in vain. I asked my friends what I was good at. I went back in time searching for my talents, trying to discern a pattern that could point me to my passion. Once, I even meditated on the word passion for a week, hoping to receive some mystical message as to what that “one thing” was for me.

But there was no “satori” (sudden enlightenment) moment.

Talent is overrated.

After I finally stopped asking questions, writing fell into my life. I had journaled consistently in the early mornings for several years, and I began to cultivate an interest in both writing and reading. I read about the lives of famous writers. I was especially fascinated by the memoirs of Ernest Hemingway, Stephen King, and Haruki Murakami.

Hemingway, for all his unruly ways, was a remarkably disciplined writer. Each day, he would write on the wall the number of words he had produced. Murakami would get up early, write for four to five hours, and then go for a long run. Because I also see running and writing as connected solitary practices, Murakami’s life especially resonated with me.

Writing is one of the hardest pursuits available to us. I know that I’m competing with millions who are better than me. I’m not interested in the fame, publicity, or money—rather, what intrigues me most about writing is the feeling of deep satisfaction I get after reaching my target for the day.

The deeply focused work required to get anything done and the solitary nature of writing appeal to me. I even love the days I have writer’s block, as that is a direct message that something is not right in my mind or my life.

I will not deny that some people are born with more talent than others, but I also believe that talent is overrated. What matters more than talent is the cultivation of craft—be it writing, golf, chess, or anything else.

Instead of “following passion,” I think a better aim is to find something that piques our interest and then satisfies us so much that we are willing to put in enough hours to master it.

This pursuit must resonate with us, excite us, and motivate us if we are to sacrifice our time to cultivate a craftsman mindset. We will get up at four in the morning to write that chapter; we’ll drive an hour on Sunday morning to be the first person teeing off at the golf course.

Apprenticeship.

The idea of learning a craft from a mentor and developing it over many years has nearly been forgotten, but it was prevalent at the time of the Renaissance. Artists learned their trade through mentorship or apprenticeship and took baby steps toward becoming full-fledged craftsmen.

At the age of 14, Leonardo da Vinci was apprenticed to the artist Andrea di Cione, known as Verrocchio, whose workshop was one of the finest in Florence. Only after seven years did he qualify as a master; he could then set up his workshop.

The idea of apprenticeship was not confined to the arts, but extended to all kinds of artisans and professionals. Aspirants learned their craft, patiently and meticulously, before displaying or selling their wares to the public.

The popular documentary “Jiro Dreams of Sushi” follows chef Jiro Ono, who has dedicated his life to perfecting the art of making sushi. He runs a three-star Michelin restaurant, for which he painstakingly buys, produces, and serves his sushi. The restaurant has a six-month waiting list, and Jiro has aspiring apprentices pleading to join his kitchen. He expects each apprentice to master one part of the sushi making process at a time—how to use the knife, how to cut the fish, and so on. One apprentice could only cook the eggs after training for 10 years.

How to reach mastery.

In Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell popularised the concept of the 10,000 hours of dedicated or deliberate practice to reach mastery in a chosen field. He used the findings of Dr. Anders Ericsson’s 1993 landmark study as a basis for his book. The study looked at a group of violin students in a music academy in Berlin and found that over the course of 15 years, those students who achieved elite level had practised 10,000 hours or more.

However, Gladwell sensationalised the findings, particularly around the 10,000 hours required to reach mastery, and he was wrong to underscore the importance of how long we practice.

Later, Dr. Ericsson clarified that the 10,000 hours of practice by some performers did not necessarily mean they reached elite level. It was just a number they achieved. He also noted that the practice they performed was purposeful practice, which as Ericsson says, “entails considerable, specific, and sustained efforts to do something you can’t do well—or even at all. Research across domains shows that it is only by working at what you can’t do that you turn into the expert you want to become.”

Nonetheless, Gladwell’s big point is still relevant. In a way, he redefined the craftsman mindset for our age. To dedicate oneself to craft, hobby, or sport, one must both put in many hours and practice in a deliberate way. Whether it’s 10,000 hours, 10 months, or 20 years is not the point.

Our world has become so obsessed with instant results that we’ve sacrificed our quality of life. The millennial age needs a return to the craftsman mindset. Through it, we will relearn how to enjoy the details and beauty of life, engrossed in the present.

~

Author: Mo Issa

Image: Flickr/George Thomas

Editor: Yoli Ramazzina

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply