Although both the temperatures of late August and the calendar tell us that summer isn’t over yet, teachers and school staff know better.

Summer is done. Put away the sunscreen and turn off the Netflix—it’s back to school time again.

School buildings are full of teachers planning lessons, building bookshelves, and creating bulletin boards. Librarians are assigning bar codes to brand new books. The front desk team is whittling away mountains of paperwork and entering data. The buildings are filled with the smell of supplies and kickballs and sometimes the laminator overheating as teachers scramble to get hundreds of names mounted onto desks and cubbies.

The air buzzes with creative energy and that collective passion to make a difference in the lives of countless individual children.

As school nurse, my August days were filled with creating charts and compiling health records of every incoming student. Ordering supplies, calling parents for doctors’ orders, and calibrating the audiometer for all the hearing tests I would do during the year. Creating a “Lost Teeth” bulletin board that would be covered in hundreds of signed and dated tooth stickers by the end of term.

We, as staff, had a multitude of different jobs, but we shared one common goal: nurturing each unique child to grow into their fullest potential.

Every school year began a week early with teacher in-services: A welcome meeting, followed by staff development, CPR certification, and classroom set up. Paperwork for insurance and payroll. Lunch and recess duties assigned.

One year, as we gathered at long cafeteria tables that first week back, we listened to an excellent presentation on bullying. How to identify it. The harm it causes. How it doesn’t always present the way you think it might. And, while a lot of teachers were nodding their heads along to the speaker, one teacher raised her hand to interject.

“Well, how do you know when it’s actually bullying and not just a sensitive kid needing thicker skin? You know, toughen up a bit.”

I was stunned speechless. Which was actually a good thing because nothing nice was going to come out of my mouth at that moment.

The speaker, a counselor and therapist, clarified the distinction between kids being kids and kids behaving in ways that are harmful to others. But, this teacher—as well as few others like her—still didn’t get it. They were of the mentality that some kids just need to learn to stick up for themselves, rather than that bullying was wrong and where we needed to focus our energies.

They weren’t at all recognizing the colossal damage that bullying causes.

When I was 14 and happily oblivious to the more negative side of the world, I was given a quick, yet thorough, first-hand tutorial on “mean girls.” And this was in 1981, before that was even a movie or a thing. I innocently went home from school one December day for winter break, and when I returned two weeks later in January, I was persona non grata, and the object of whispering and staring. Teenage girls, who loved some good drama, so easily believed ridiculous rumors that had been created out of thin air. My friends were threatened with joining me in my exile if they so much as looked my way—and there were threats of physical harm.

By year’s end, all was forgotten by every girl involved. Except of course, me.

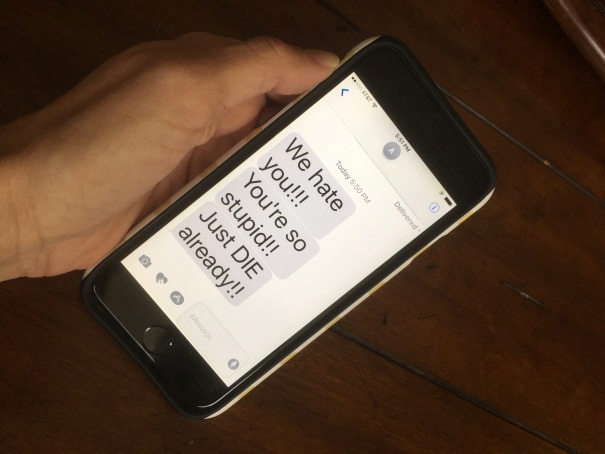

Then, when I became a mother and focused on teaching my kids empathy, compassion, and the golden rule, I watched my first 14-year-old daughter get bullied by the girls in her class. Two years later, my second 14-year-old daughter had her turn as a victim, only she was bullied to an even greater degree because now the bullies had the internet and social media.

The ability to take someone down had grown exponentially.

Our three stories, occurring over 25 years, had two major things in common: one, nobody stepped forward to stop the bullying or protect us, and two, the damage done to us was irreparable.

What a bad combination.

So, in the current climate of children killing themselves after being repeatedly bullied, when do we, as adults, decide to make it a priority? In a worsening climate of intolerance, how many children have to take their own lives or become a statistic in other ways before we put a stop to it?

Whose responsibility is it?

Well, whose job is it to stop kids from flying out of cars when there’s an accident? It’s the job of adults—through designing car seats and seat belts, through parents insisting that kids be buckled, and through legislation requiring that we do so. And we gladly take that responsibility because we believe our child’s life is an extremely high priority.

And, whose job is it to keep kids from drowning? Do we expect kids to just swim, or do we, as the adults, accept responsibility not only to teach them to swim, but also never to leave them unattended near water? And why do we do this? Again, because we’ve made our kids’ lives and safety a priority.

We do the same with dental hygiene and not running in traffic, because on the hierarchy of priorities, we consider all those things crucial to in our children’s lives. But where does protecting our kids from bullying lie on that list of priorities? Is it below seat belts but higher than washing your hands before dinner? Is it even above getting straight As, or a high SAT score?

And, if not, why isn’t it?

What happened to our common goal of nurturing each child to their fullest potential? Students who are bullied do not feel safe, and when a student doesn’t feel safe, they cannot learn. And, if we, as educators and ancillary school staff, do not protect students from being bullied, we are singlehandedly denying them an opportunity to learn, as well as setting them up for a lifetime of psychological damage from allowing their basic needs of safety to be challenged .

Feeling safe is their unquestionable right. And protecting them is, undeniably, our responsibility.

The National Education Association reports that one child is bullied every seven minutes, and in schools across America, one in three students reports being bullied weekly. In 2010, up to 98 percent of surveyed teachers considered stopping bullying a high priority, but they don’t know exactly how to do it.

In response, the NEA put together a toolkit for educators and parents teaching them to identify, intervene, and advocate.

>> Identify: Bullying is systematically and chronically inflicting physical hurt and/or psychological distress on another; it can be physical, emotional, or social; and it involves a real or perceived power imbalance between the one who bullies and their target.

>> Intervene: Students who bully must hear that their behavior is wrong and harmful to others, and students who are bullied must hear the message that caring adults will protect them.

>> Advocate: Educators can start by signing the NEA’s “Bully Free; It Starts with Me” pledge, promising students that you will listen, that you will protect them, and that you will advocate to other students and to other school staff to end bullying.

Educators please visit NEA to learn how to put an end to bullying. Sign the pledge here and download the toolkits here. Another great resource is stopbullying.gov.

From parents to teachers, nurses to librarians, substitutes to administrators, bus drivers to paraprofessionals, at lunch and at recess, and in the halls and bathrooms, we have to work together to end this worsening crisis for our kids—because it will never end until we do.

~

Author: Amy Bradley

Image: Author’s Own

Editor: Catherine Monkman

Copy Editor: Callie Rushton

Social Editor: Callie Rushton

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply