On the morning of my 16th birthday, my parents and sister bustled into my room and dragged me, half awake, out of bed.

They led me toward my window. There sitting on our lawn was a shiny, black Mazda 323 with a giant, white bow affixed to the roof. It was a shocking surprise.

I remember how pleased I was driving into the school parking lot later that day. My boyfriend had just dumped me for my best friend and the look on his face was awesome. The car was freedom. I was set.

What I didn’t know in that moment is that it would be just under two years from that day that I would be lying swollen and broken in critical care.

It was March 1993. I had just dropped my two-year-old sister off at daycare. I was driving fast and trying to make it to class before the bell rang.

I grew up on dirt roads. The cardinal rule was to keep to the center of the road—steering clear of the soft shoulders and loose gravel. I was following that rule, too closely, too carelessly.

Coming over the crest of a hill, there was no slowing my momentum—I still owned more than my share of the road, and I barreled head-on into another car. By the police officer and other bystanders’ account, I swerved right. My car dipped too far into the ditch. The machine was bigger than I could handle. I over-corrected and shot across to the other side of the road; it was out of my control. The car cart-wheeled twice down a ravine before coming to an abrupt stop.

The sound of gravel and metal colliding is dark and dirty. The woman I swerved to avoid wasn’t able to turn back for fear of what she might find; she kept driving to the next farm house to get help. The couple in the next car that passed stayed by my side until the paramedics took over.

The “air ambulance” brought me to the hospital, but I don’t remember the ride.

Over the next 24 hours, there was surgery and then critical care. My first memory was being wheeled back from surgery and seeing the blurry outline of my mother. It all replays now in a flash of kind nurses, a lot of popsicles, the moaning lady who roomed with me (she had broken all her limbs), and a lot of well-wishers.

The first time I sat in the shower chair and looked down at my naked body, I was shocked to see every version of black, blue, and purple covering me. The first time I tried to spell words after the crash, I didn’t know how to write. My femur was broken. I had a head injury. My ribs were fractured, and I had punctured my lungs. I was alive though.

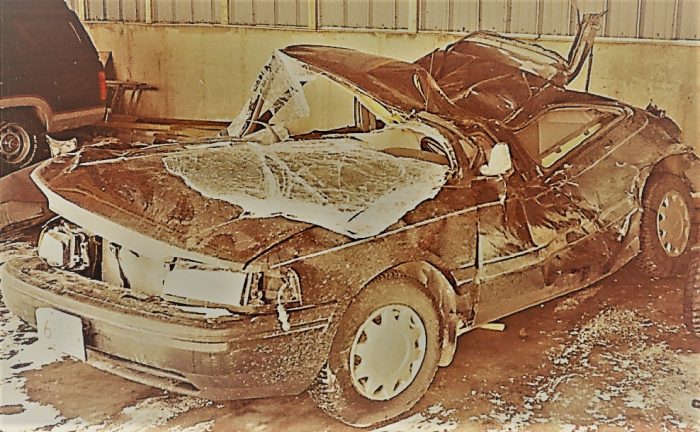

I don’t know what happened that day to save me. That car folded up like a ball of tin foil. I wasn’t wearing my seatbelt. I wasn’t dismembered or disfigured. I could walk. My brain would eventually catch up to speed again.

However, long after the physical scars thickened and my bones and brain healed, something about me remained forever changed.

There is a moment in all of our lives when the illusions of youth concede to reality; a time that breaks the spell of permanence in this world and opens us to the knowing that we are not invincible.

The accident claimed my remaining innocence. It was the moment where I finally reconciled with the fact that nothing in life (beyond our response to it) is in our control. This was a part of growing up—learning that bad things happen.

Furthermore, I lost the sense of freedom that exists in our minds when we are young—that impulsive, act on a whim, free of consequence behaviour. That girl was gone. I was no longer infallible. I could die tomorrow and that scared the sh*t out of me.

Fear finds us no matter how long and how hard we try to hide. It meets us in our vulnerabilities and chases us in our weak places.

I started having anxiety attacks within the first year after the accident. It wasn’t long before heart palpitations and chest tightening escalated into symptoms of breathlessness and numbness in my legs. Weeks of full body rashes landed me in the hospital. I thought it was the stress of college and that it would go away.

It didn’t.

My doctor brought up “anxiety” and recommended medication. It wasn’t something I was comfortable with. I filled the prescription but never took a pill.

I leaned toward the avoidance method. The moment I’d start to feel the anxiety build, I would try to focus elsewhere—affirmations, self-talk, the horizon.

It didn’t work. It actually got louder.

Then, one day I did something different. I was driving on a major highway and cars were whizzing by—typically a place where panic caught me the most—when I thought I had no control of anything around me. I desperately tried to escape it and push the angst aside. And then it occurred to me that I had already lost the worst kind of external control of my life, and I had survived. I could survive this. I put my hand on my heart. Breathing into my fear, I knew it was time to stop running. The key all along was turning into it.

Sometimes, we learn things in life that, at the time, we have no idea will be of use to us but permeate deeply in our subconscious waiting for the right moment to surface.

In grade school, we had a local police officer come in. He told the story of a boy who lost his life tragically when he wasn’t wearing a seatbelt in the car he was driving. Every time I got into a vehicle after that, and didn’t have a seatbelt on, I had a habit of assessing how I could pin myself into position in the event of an accident. That habit was so ingrained by the time I was in my teens that it became second nature.

Months into my recovery, I was playing one of those virtual racecar games where you sat down and mimicked driving. There was a point that the racecar lost control and started to flip end over end. For a second, I returned to that March day. I vividly recalled the car cartwheeling and pinning myself between the steering wheel and seat, leaving me holding on for dear life.

The universe works on its own accord and delivers us the answers in its own perfect timing.

For a long time, I wanted to find the couple who were first on the scene after the collision.

I hunted for them. I made phone calls. I found out where the man worked and promptly went there. To no avail, he had left for another job. I gave up.

Several years later, I was working at a trade show and offering five minute massage therapy demos. The man from the booth beside me was complaining of a sore shoulder, so I invited him to get on the table. We began chatting. He asked me where I grew up, and I named the small town. He knew of the area and told me a story that was eerily familiar.

A few years ago, he and his wife had decided to take the day off and go for a morning drive. Twenty minutes into it they happened upon the scene of an accident. The dust still ballooned in the air when they pulled over to help. Bravely, they walked down into the ravine. When they came around to the driver’s side of the car, they found me. They were baffled:

“We expected to find you dead, but there you were lying perfectly placed just like an angel had caught you when you fell out. There was a presence there that couldn’t be named. It seemed impossible how you got into that position and the look of peace on your face is an image that we never forgot.”

Looking back at photos from the wreck, I say a silent prayer. I got lucky. Not just because I lived, but because I walked away intact and without the burden of knowing I maimed or took someone else’s life. Being tiny and a fighter saved me.

The accident changed the course of my life. It acknowledged for me that life is both fragile and unknown. That it has its own heartbeat—one of strange synchronicity that connects all things.

~

~

~

Author: Kristen Dobson

Image: Author’s Own

Apprentice Editor: Gin Carter/Editor: Travis May

Social Editor: Taia Butler

Read 1 comment and reply