My 24 year-old sister, Char, twisted a stray string from my mother’s comforter as I, 19, spun my late grandfather’s wedding ring (a gift from my mom) around my pinkie.

We sat in my mother’s bedroom—her sanctuary and prison—as she looked out the window longingly while the afternoon sun bathed her cherry pine sleigh-bed on this stunning July day.

Kept away from tending to her roses, from smelling strangers’ baby’s heads, and from the theatre where I was performing in a musical that summer, Mom was getting cranky. Hindered by dry lips but motivated by restless legs, she pleaded, “You guys have gotta get me out of here,” and with a coy smile said in her best Jewish grandmother voice, “I’m dyin’ in here.”

Morbid, mom.

Char and I exchanged a skeptical glance as we looked at the tubes and machinery she was connected to that somehow controlled the bag of nutrients keeping her alive and considered the implausibility of any excursion. Though Mom clocked in at 5’2’’ and under 100 pounds, Char and I knew a battle was fruitless; when mom set her mind to an idea, we had no chance of stopping it.

Accepting defeat, we carefully guided Mom into the passenger seat of her yellow Volkswagen Beetle and drove to Crescent Bay Park in Laguna Beach. Left arm clasped to mine and right arm clasped to my sister’s, my mother shuffled down the pathway leading toward the water. With a halt, she informed us that to our right was a crop of angel-wing jasmine. “You guys have to smell these,” she coaxed, with that same look she would have when confronted with a piece of chocolate cake—eyes wide, and looking guilty for how indulgent she was being. We agreed, but I just watched her as she closed her eyes, dipped her face into the small, star-shaped flowers, and drank in their scent as if they were a life force.

We continued down the path toward the edge of the cliff—a meeting place between two worlds—and pressed against the railing overlooking the ocean. The three of us stood, hand-in-hand, and our eyes softly closed as the sun warmed our skin and the sea-salt mist caressed our faces. For the first time in the six years since she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, our shoulders released. We breathed fully and a sense of ease swept over us.

A self-identified “flower child” who read Pema Chödrön and Thích Nhất Hạnh, my mother had a penchant for uttering mystical statements that would knock you off your feet. Six months before her death, for instance, she sent a care package to my dorm at UC (University of California) Berkeley filled with my favorite snacks and some athletic socks with a card signed, “I love you, eternally.” Eternally? What cancer patient references their impending death and everlasting spirit to their child on a note next to a candy bar? Jeez, mom.

She rose to the occasion in this instance as we stood next to the ocean. While taking in the power of the sea with mist in her eyes, she said with the surety of a new discovery, “This is where spirituality lies.” My mother found God while standing at the edge of the world, hands clasped with her children, drinking in the power of the sea, and staring death in the face.

Months prior to this experience, following particularly intense rounds of demoralizing chemotherapy failures, I’d asked my mom if she was afraid of dying. Having faced the possibility of her death over a total of 16 years, she said that she wasn’t so much afraid, but more confused and angry, and also saddened by it. “Leave this? Leave my babies behind?” she said her eyes welling up, “I can’t fathom it.”

But standing at the cliff, nearing the end, and marveling at the supreme beauty of the universe, something in her had shifted. Her, “Not this time cancer, you’re not going to f*ck with my family,” mama-bear-survivor stance was replaced by a calm acceptance. My sister and I followed her lead.

In fighting cancer, one faces a continual onslaught against their body, mind, and spirit. The body betrays you. In its 16-year assault on my mother’s femininity (did I mention she had another stint with breast cancer when I was three?), the disease took my mother’s hair, breasts, ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, and a third of her intestines.

Remarkably, though, as she became progressively more dehumanized, her humanity grew. Following her first diagnosis, she and her closest friends championed a non-profit called Healing Odyssey, a woman’s retreat for cancer survivors. At this camp, among other activities, women got in touch with their power by inching their bodies out over the edge of a cliff—much as we did on that day—and facing what we all know as the deepest, most core human fear. They call it “The Edge.”

Mom took us to the edge that day with her. Standing above the ocean and coming to a place of acceptance of the inevitable, my sister and I also looked death in the face. It is truly impossible not to consider your own death when someone you love is facing it, especially when that person happens to be someone you love more than anyone on the planet—the person whose body you came from, the person to whom the very senses of your body are trained to seek in times of distress.

When confronted with death in this manner, what truly matters quickly shifts into focus; it becomes glaringly obvious that our time here is so finite, and death can come at any moment. As horrific as this experience is—one that I wouldn’t wish upon anyone—there is much to be gained from confronting mortality.

I am a more grateful person today as a result of losing my mother. She died six days after our experience on the cliff. As I watched her fight with everything she had to stay on this planet in order to spend another day with my father, the love of her life, and be here to support Char and I through our trials and triumphs, I began to value my life more. I, of course, had moments when I raged at the top of my lungs at cancer, and I was unfathomably changed on the warm July morning when the man from the morgue wheeled her body out of our house. But my sense of gratitude was also undeniably shifted.

Nine years following my mother’s death, while pursuing a doctoral degree in clinical psychology at the Wright Institute, I was studying loss, childhood trauma, and resilience (in grad school, we called this “me-search”) and wondered about whether there might be some universality in the experience of one’s gratitude growing through loss.

Early on in the process of compiling my literature review, I discovered a study from Frias, Watkis, Webber, and Froh that showed that one’s sense of gratitude can increase as a result of reflecting in a personal way upon one’s own death. The authors of this study attributed the phenomenon to the “scarcity heuristic,” whereby we value things more when they are rare or scarce. So when we’re faced with death, the value we place on life rises. This was my experience. In witnessing my mom die at 53, suddenly life felt very short, and each moment became incredibly important.

I became excited about seeing my experience mirrored back to me in a psychology article and was inspired to devise a study to determine if losing a parent in childhood made people more grateful. The purest form of this study would be a multi-year longitudinal study that measured people’s gratitude levels before and after the death of their parent, but that unfortunately wouldn’t fit into my two-year dissertation window. I was trying to graduate, after all.

What I was able to study, though, was the dispositional gratitude (a psychological construct that refers to a life orientation toward gratitude and appreciation) in the experience of 350 adults who had lost a parent, as well as their perceptions of how their gratitude changed as a result of the loss. My chair, Dr. Katie McGovern, and I also studied the relationship between gratitude levels and depression, psychological well-being, and post-traumatic growth. Unsurprisingly, we found that those who rated themselves higher on measures of dispositional gratitude reported lower levels of depression and greater levels of psychological well-being and posttraumatic growth. In other words, the more grateful participants were faring better than those who were less grateful.

Even more interesting to me though, was our finding that 79 percent of those we surveyed reported that they believed that their experience of gratitude increased as a result of losing their parent, as opposed to roughly 13 percent of those who reported no change in gratitude related to the loss and only 8 percent who reported that their sense of gratitude decreased as a result of the loss. A large majority of the adults in the study felt as I did—that losing their parent made them a more grateful person.

In order to understand this in a more nuanced way, we invited people to write about how they understood the relationship between the loss of their parents and their sense of gratitude, and coded the responses for themes. The most common themes that people reported were related to realizations that life is precious, feelings of gratitude for family and friends, and a newfound recognition of impermanence. I was particularly moved by a quote from a woman in the study:

“Losing my mother reminds me daily how precious life is and that I shouldn’t take a single second for granted…From darkness I eventually came into the light.”

Inspired by the findings, my chair and I published this study in Death Studies, a psychology journal that explores death and bereavement.

My mother was a wonderful, thoughtful person who facilitated as much of a “good death” as she could. While I used to view her jokes about mortality and “I love you eternally” notes as odd and uncomfortable, now that she’s gone, I recognize that they were part of her larger campaign to prepare Char, my dad, and me for her death. As part of my mother’s unstated campaign, she thought ahead to the important events she would miss and wanted to remind our future selves that she was there with us.

For instance, she wrote letters to us to be opened on our wedding days and she recorded herself on a Walkman reading my, and my sister’s, favorite childhood stories so she could read to her future grandbabies. It was so painful to see my mother suffer over multiple years, but due to the slow progression of her disease, we were given the gift of time. And in that time between diagnosis and death, we held one another and laughed and cried together as much as we possibly could.

So when I entered into this research about loss and gratitude, I wanted to make space for the possibility that not everyone who had lost a parent had experienced a “good death” as we had. They may not have been given the opportunity to say goodbye or had a parent who was so conscientious about preparing them for the death, and they might have had troubled relationships with the parent, or that parent may have even been abusive to them.

As was the case, I also wanted to study why it was challenging for some to access gratitude following the loss. We found, unsurprisingly, that those who had additional traumatic events over the course of their life were struggling more, and the most common reasons that people attributed to their gratitude decreasing following the loss were fear, anxiety, a feeling that they couldn’t depend on others, and other difficult situations in their life inhibiting them from feeling grateful.

It was important to me to explore the experience of those who did not, in fact, see themselves as more grateful following a loss, as I didn’t want the research to paint an unrealistically rosy picture or minimize the incredible emotional pain that comes with losing a parent. And the last thing I wanted was for those who were having a hard time to feel like they should be feeling grateful. Similar to research participants who reported fear and anxiety, I have experienced a host of negative impacts due to the loss of my mother as a teenager, and I most certainly do not feel grateful every day. I become angry every Mother’s Day and feel shame about the occasional envy I feel toward my best friend’s one-year-old son when I witness the beauty of their connection, and, as an adult man, still yearn for that with my own mom.

Though I experience a range of negative feelings about the loss of my mother, I also know that my grief has served as a portal. It has given me a window into how fiercely I can love in the face of death and has opened me to a depth of experience I didn’t previously know was possible.

My sister describes this feeling as “the burden of being awake.”

In living with this incredible burden and gift of parental loss, no feelings are simple or singular. In every accomplishment or milestone achieved, there is a tinge of melancholy as it serves as a reminder that the world has continued spinning without my mom in it. And in the overwhelming wave of sadness I feel envelop my heart when I smell her perfume worn by a stranger or wake up from a dream in which she visits me, there is also a deep aching joy in feeling connected to her. And this is the gift of grief: an opening to the complexity of moment-to-moment experience and an awakening, which, for me, inevitably gives way to gratitude.

In moments when I yearn for my mom—in the aftermath of my painful divorce or when I celebrate achieving a doctorate or want to share my excitement about newfound love—I visit that cliff on the edge between two worlds and visit her. She was right. This is where spirituality lies.

~

Relephant:

The 4 Reminders that Turn our Minds Toward Sanity & Cheerfulness.

~

~

~

Author: Dr. Nathan Greene

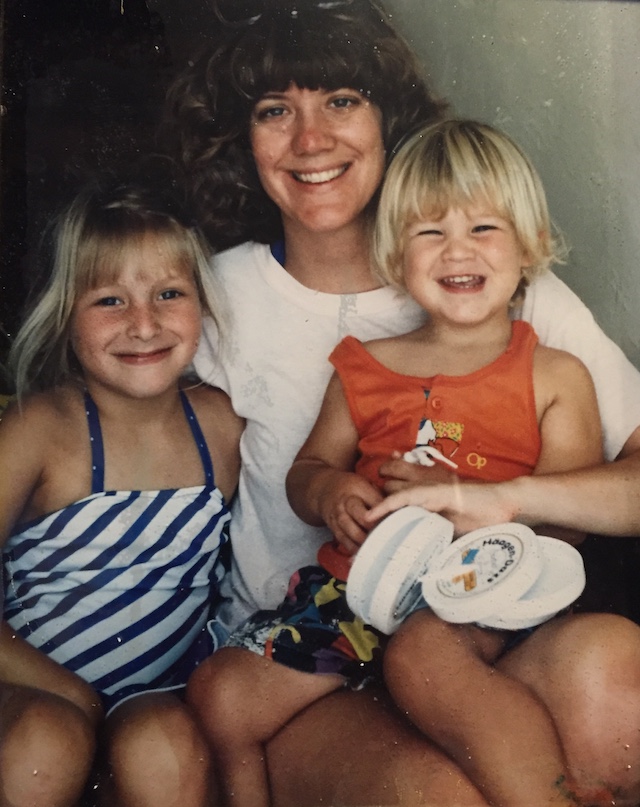

Image: Author’s Own

Editor: Travis May

Copy Editor: Catherine Monkman

Social Editor: Waylon Lewis

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 11 comments and reply