I stood in the doorway, half in half out, momentarily frozen and confused by my mistake.

Joan, you understand, wasn’t one of my patients and I’d entered her room in error.

It was too late.

As I focused upon her, I realised that her gaze was now fixed upon mine.

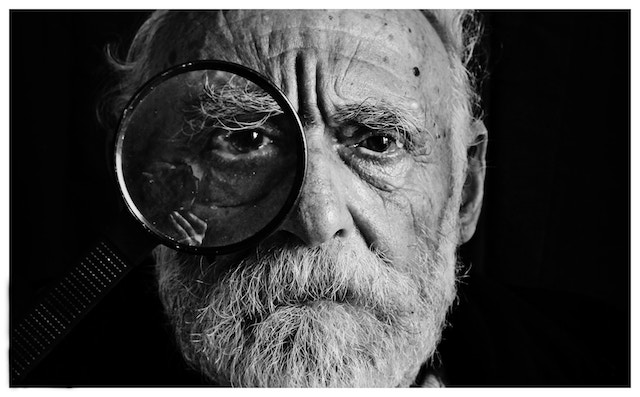

Her eyes, long since dulled by age and dementia, seemed unusually lucid in that moment—acid clear and sharp in their foreboding.

At first I made to withdraw from the room, stepping back and smiling by way of an apology. However, it then dawned upon me that Joan, lying silently still in her bed, was waiting. Alone.

I could have left that room and called for a nurse. We’d known that her last hours and days were at hand.

Somebody should have been assigned to her side. Someone should have been there, waiting with her for her last breath to rise and then, finally, to fall.

I couldn’t leave. There was a heaviness to the atmosphere in that room, a sense of imminence, and her stare was a pull. There was a magnetism to that communication, an unspoken message in those eyes of urgent significance.

I didn’t leave. I realised that this moment had fallen to me, and so I sat beside her, taking her hand in mine and very much aware that I would be the last person on Earth to feel its life.

Sitting with the dying can be a peculiarly entrancing experience. The world ceases to turn and each cloyingly eternal moment is suffused with a heaviness which defies explanation and which drains the energy from your own being.

As I sat with Joan, she continued to gaze into my eyes and her fear seemed to ebb as I spoke to her in warmly reassuring tones. I can’t recall what I said. I don’t know if she understood the words, but she was no longer alone. She had been given the company she’d awaited as she took those final steps beyond life.

Within a minute she was gone. A life snuffed out. A history lost to the world.

Nobody had ever visited Joan whilst she lived in her nursing home. No cards had come for birthdays or Christmas. She was forgotten. Old, demented, and decayed, she lived out the final months of her life being fed, washed, and cared for by strangers. Whatever lay preserved within the ruins of Alzheimer’s was irretrievably lost to the world.

She was now simply a biomedical problem to be managed in its decline.

Where was the person?

Once she had been young and replete with youth’s false promise of eternity. Her skin had clung tightly to her bones and the flame of her vivacity had shone through every pore.

In her youth she had lusted and been desired in her turn. She had given birth, lived, hoped, and loved. As she aged, a wealth of stories and wisdom accumulated within her ever-expanding tome of experience. Behind her eyes a book was in writing, the tale of a world which retreated from sight with every death of the wartime generation.

One last breath, and that was it. A history, a treasure, a library consigned to the flames. Who had ever captured its contents? Had anybody bothered? Did anybody harness the stories of this woman while she was still capable of giving them?

Did anybody take the time to learn from her? Was she simply another old lady, passed and ignored by those too busy to stop and wonder before she slipped, unnoticed, into the hades of dementia?

Another patient, Bert, was a tall man in his 80s. He spent his time endlessly shuffling along the corridors and around the day-room of his final home, stubbornly resisting all encouragements to rest. Sometimes he would walk himself into a corner. There he would stay until he was rescued, his feet shuffling against the walls of his 90 degree prison as if he were a wind-up toy.

If he were to meet you on his travels, he’d take and shake your hand, smiling a broad and toothless grin. Having gained your attention, he’d then proceed to breathlessly and ceaselessly repeat one of two phrases. The first was “my wife…”

There was more, much more, to be said on that topic. That much was plain, and yet the words were lost inside a fog. How he tried, and failed, to find them.

The second phrase ran as follows: “l’ll kill you…with a laser gun.”

This futuristically menacing message was delivered with that same, endearing grin.

What ghosts were locked inside Bert’s mind are now mysteries long since lost to the grave. He was no statesman, no king, nobody of any note at all. Nevertheless, he had a story to tell and I was simply far too late to hear it.

I later learned, after his own unremarkable death, that he’d murdered his wife in the 70s. A laser gun may or may not have been involved, and how this gentle, friendly man came to commit such an awful deed will forever be an unfathomable enigma.

This is why I have resolved to spend 2018 talking to as many strangers as are willing to tell me their stories.

There’s a whole planet full of tales to be heard, a mine of gems in every mind, and I haven’t a minute to

waste.

People, people, people. Survey after survey, experiment after experiment, proves that we gain our happiness from others.

Resolve to ensure that 2018 is your most people-focused year of all. Build those links, restore those connections, reach out in order to give and receive. Ask and share. Love and be loved.

Will you become just another old lady among a sea of others? Are you the lonely widower-in-waiting? Are you simply too busy to stay in touch? Is that piece of work really so important that you can allow your partners, children, and friends to grow old around you, unnoticed?

If so, Joan and Bert would like to have a word with you. After all, they know what matters most.

Author: Paul Hughes

Image: Mari Lezhava/Unsplash

Editor: Emily Bartran

Copy Editor: Nicole Cameron

Social Editor: Catherine Monkman

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply