Since 2009, the Yoga Service Council has supported organizations that teach yoga and mindfulness to underserved populations.

The council’s former president, Rob Schware, says the membership-based collective was born out of a need, expressed by those bringing yoga to diverse populations, to make the field “more professional and ethical, effective and sustainable, ethical and socially just.”

In 2012, overwhelmed by exponential growth and motivated by significant needs for ongoing education, the Yoga Service Council partnered with the Omega Institute. Together, they developed the Best Practices series, which supports the annual volunteer gathering of up to 30 professionals in a particular field of service, from those who offer yoga to incarcerated students to those who work with survivors of sexual trauma (a population with immense overlap, a Best Practices book might point out). Each volunteer professional contributes the research and experience-based knowledge vital to the collaborative writing process for each Best Practices publication.

Best Practices for Yoga and Schools, for example, published in 2015, focuses on best practices for developing sustainable and effective yoga programs in schools. The second guide, Best Practices for Yoga with Veterans, published in 2017, focuses on yoga with men and women involved in the military. The Yoga Service Council’s third book, Best Practices for Yoga in the Criminal Justice System, was released last month, followed by Best Practices for Yoga with Sexual Trauma Survivors, is forthcoming in spring of 2019.

In 2012, I began teaching Trauma-Sensitive Yoga in the post traumatic stress. wing of a Veterans Hospital in the Bronx. During the two years that I led a weekly class, I embarked on a series of interviews with veterans, military officials, and healthcare professionals examining the role of mindfulness in the military. This is how I found myself among 20 other contributors at the Omega Institute in the fall of 2015, working to condense and clarify what we have found to be the most useful, thorough, and conscious offerings of yoga with those involved in the military.

*

Yoga is practiced by over 20 million Americans and is an industry that grosses $5 billion a year. Yet for all its established popularity, as the practice enters new cultures, it resurrects timeless questions, such as the question that begins the classic yogic text, the Bhagavad Gita, as the warrior Arjuna pauses on the edge of the battlefield and cries out, “How shall I live?”

I began the process traveling, conducting interviews, and researching yoga in the military because I wanted to know how this ancient, Eastern tradition was helping modern day veterans answer this same question posed by Arjuna. How was it helping them live?

Since 2002, more than 300,000 servicemen and women have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress at hospitals for veterans. As many as 40 percent of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans treated at such facilities receive a triple diagnosis of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), traumatic brain injury, and pain. This Human Rights Watch report notes that nearly 50 percent of accidental deaths among soldiers between 2006 and 2009 were caused by substance overdose. Seventy-four percent of these overdoses involved prescription drugs.

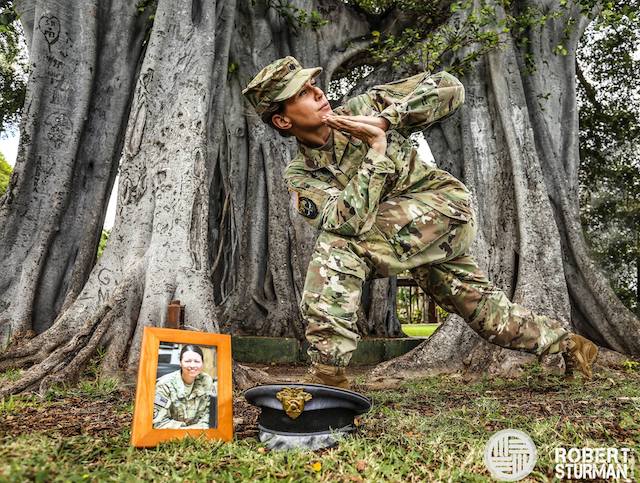

Military men and women often attribute profound shifts in perspective and lifestyle to their yoga practice. They tell me how the practice has helped them process grief, sleep again, relate to loved ones, find a path toward self-forgiveness, and meet triggers with increased compassion and less shame.

Many have embarked on a yoga practice in order to sustainably transition out of active duty, maintain relative balance throughout multiple deployments, and survive devastating injuries. Often, because service is so fundamental to their well-being, they continue down a road of healing by becoming yoga teachers themselves. They have a transformed sense of identity and purpose. They see things differently. And their practice, in turn, is causing the landscape of American yoga to look a little different too.

*

On a baking hot Memorial Day in 2016,” I walked through Arlington Cemetery with my friend Ben King. After returning from the war in Iraq in 2007, Ben was forced to confront increasingly relentless symptoms of post-traumatic stress.

After unsuccessfully trying to control his symptoms on his own, Ben reluctantly attended a yoga therapy class called iRest, offered at a VA hospital outside of Washington D.C. After that first class, Ben’s path carried him into years of his own mindfulness practice, eventually becoming a teacher himself and founding a non-profit initiative called Armor Down, helping veterans anonymously and freely obtain guided meditations through their smartphones.

For the third Memorial Day running, Ben and his non-profit team had organized Mindful Memorial Day, creating space for 6,852 yellow ribbons to be hung in the gateway of Arlington Cemetery. Each ribbon includes the name, age, hometown, rank, and date of death of an active duty service member that died since the invasion in 2003.

For three days, I watched Ben welcome thousands of people through the door, sometimes tracking down overheated school kids and blank-faced tourists, encouraging them to not be afraid, or helping family and friends of loved ones to seek out a specific ribbon. Perhaps because of his nature, or perhaps because he had encountered the very delicate, finite boundary of his own life, Ben’s daily loyalty to service—a larger sense of self—had become integral to how he survived.

Ben and I squished through the muddy earth that lined thousands of ivory headstones, some sprinkled with bouquets and miniature American flags. We were looking for someone in particular, a grandfather of a young woman who had written Ben and asked if we might take a moment to visit her grandfather’s grave. When we found his headstone, we learned that the man had fought in World War II, Vietnam, and Korea, and had lived into his nineties. I perched and Ben sat in the wet grass for a long moment of mutual silence, of sacred incomprehension, before we rose delicately and started back toward the memorial.

On the way, we passed a lieutenant, wearing full uniform and a spread of gold medallions on his chest. I reflexively gave a small smile and averted my eyes while Ben shouted, “Looking sharp, Lieutenant!” and gave him a clean salute. I let out a little laugh at this difference as we kept walking, meandering around the topic of how ideals of patriotism had become politicized. (How had an American word as ubiquitous as “freedom” come to represent only a few of us?)

This lead Ben to share his theory that the “healers” of America (the yoga teacher types, a predominantly liberal population), and the “warriors” (those involved in the military, a predominantly conservative one), had differentiated themselves too much from each other, largely for political reasons. “But we go together, we need each other, we have for centuries. It’s a bad sign for society when the warriors and healers are so far apart.” With his typical, lean acuity, Ben nailed a cultural sadness that I myself had been interested in, felt, and witnessed.

Walking through Arlington Cemetery in the Memorial Day heat, I was acutely aware that even though my grandfather fought in the Korean War, no one in my family had served since then. In 2006, I had marched in the street in opposition to the invasion of Iraq and had been removed by police (a fact I was at first hesitant to share with the veteran friends I made, fearful that they would regard it as a cruel dismissal, though I did eventually share it with some of them.)

How was it that we had been at war for over a decade and all of my family and friends, most of whom opposed military involvement to begin with, did not know anyone directly involved? There was truth to what Ben said. And I had begun this project, and was pained by it, because on some level, I agreed with him: it is a bad sign when only a small part of a country is viscerally aware that it is at war, and the majority of those engaged in healing modalities do not have a relationship with those who fought in it.

*

For the first time in our country’s history, less than one percent of our nation’s population has born the burden of war. (Compared to 10 percent during World War II and two percent during Vietnam.) In his New York Times article “Vietnam: The War that Killed Trust” Karl Marlantes, writes:

“America’s elites have mostly dropped out of military service. Engraved on the walls of Woolsey Hall at Yale are the names of hundreds of Yalies who died in World Wars I and II. Thirty-five died in Vietnam, and none since. The American working class has increasingly borne the burden of death and casualties since the 1940s. Put another way, the lowest three income brackets have suffered 50 percent more casualties than the highest three.”

The anti-war movement of the 60s cannot be separated from the immense influence of Eastern spirituality and its import of yoga, meditation, and philosophy of non-violence. The anti-war movement, for all its good intent, deepened a social rift between those who opposed the war and those who fought in it—a rift whose wounds are still fresh for those who served, only one generation removed.

At one point during that mindful Memorial Day weekend, I paused in front of a display in the Women’s Military Memorial, staring through the museum glass at a 1960s poster with the image of dog tags, a pained rebuttal in bold letters underneath: Not all Women in the 60s Wore Love Beads.

Decades later, yoga culture continues to identify more readily with the woman who put the flower on the officer’s bayonet than with the officer himself, if the iconic 1960s photograph is worth so many words. In the book, How Can I Help? co-authored by Ram Dass (one of the central figures of the influx of Eastern thought in the 60s), that same police officer would recall that the way the young woman had placed the flower on his bayonet was palpably aggressive. She didn’t seem to be registering his humanity at all, he said, but aware only of the press and the impact her image was about to make.

Stephen Cope describes the freedom that yoga affords us as, “Freedom in the world rather than freedom from the world”—a world rife with cruelty, betrayal, misuse of power, violence, and trauma. In my experience, these difficult realities are tempting to meet with detached blame, partly as a palliative against fear.

Working as a “healer” inside of military culture, I have to keep my eye out for times when I am placing the flower in the bayonet, so to speak. It has been part of my yoga practice to realize the difference between sharing my ideals with an open mind and imposing my own prescriptive ideas of peace. The former is tough inner work that is vital for true dialogue, and the latter is its own expression of violence.

Jennifer Cohen Harper, president of the Yoga Service Council, speaking with YogaCity NYC in a 2016 interview said, “To do yoga service you need to cultivate both self-reflection and self-awareness. Understand the barriers to authentic relationships and know how to make them healthy and productive.” A spirit of listening was certainly necessary to see through a project like the Best Practices book, where diverse backgrounds and viewpoints at times challenged, but ultimately strengthened, a common cause. As Jennifer Cohen Harper says of the Best Practices series, and the diversity of its contributors, “It is an interdisciplinary understanding that makes our work unique.”

This “interdisciplinary understanding” is unfolding in veterans healthcare, which spurred by a crisis of health and a shortage of funds, is implementing an astounding amount of projects. Examples include the Pain Management Task Force, holistic health and mindfulness endorsements from the former Army Surgeon General Eric Schoomaker and Ohio Senator Tim Ryan, complementary wellness centers, such as the National Intrepid Center of Excellence, as well as insurance coverage and educational resources offered through the VA in regards to yoga, acupuncture, and massage. As Western as the American military may be, military healthcare, spurred by the mental health crisis of millions of its veterans, is becoming surprisingly more Eastern.

While there are many who see the practice of yoga in the military as incongruous, I believe it is redemptive, if not simply fair, for a nation’s practice of human healing to further define itself by moving further and further away from being conditional, specialized, and politicized. In the context of America’s history, this integration of Eastern modalities is perhaps a merging of the warriors and the healers, a division whose closure was inevitable, and a hopeful amendment to a painful part of our history: a cultural era when some of us believed that the shunning of war veterans was an effective means to peace.

Since its publication last year, Best Practices for Yoga for Veterans has become required reading for several teacher-training programs, including Connected Warriors, the Exalted Warrior Foundation, and Warriors at Ease, helping trainees engage more thoroughly and effectively with a common language of experience. It has served as a starting point for administrative staff and therapists at veterans hospitals, and a resource for veterans and their families, both within and outside of clinical settings.

The book has been described by trauma-therapists and mental health professionals as an “invaluable resource,” and by John Kepner, Executive Director of the International Association of Yoga Therapists, as a ”must read for those working in the field.” In the past year, many people have reached out to the Yoga Service Council to express their interest in the book and describe how they would like to utilize it in their work. One veteran wrote:

“I am a retired disabled veteran on the long and never-ending path of recovery and healing from many ailments (service-connected and more). Since retirement, I found that my VA group therapy, relaxation classes, and yoga have helped me more than any form of medicine. This interest has grown and has me on a constant search to learn as much as I can about how to help myself and others to deal with the struggles of these problems. Thank you for listening.”

*

What is sustainable health? How do we establish resilience in a world rife with uncertainty? How do we love when we know that what we love will be lost? What can we intelligently believe in? These are the core questions of yoga, shared through brutal experience by the survivors of modern warfare. There are an endless number of ways to enter a spiritual practice, a diversity of life experiences to bring to bear on a path that, no matter when or how it is joined, will thread us back to the fundamental question: How shall I live?

It is a question revealing itself, eventually, as one that we cannot answer alone.

~

~

~

Author: Lilly Bechtel

Image: Robert Sturman

Editor: Travis May

Copy Editor: Callie Rushton

Social Editor: Waylon Lewis

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply