As early as in Ivan Turgenev’s novel Fathers and Sons, an age old-biopic written in 1862 depicting struggles of opposing views of parents and children, society has been tackling issues of intergenerational gaps for over a century.

Children have never agreed with their parents, and the added technological advancements and cultural exposure due to increased rates of immigration and globalization just widen the gap.

Anyone who visited their families over the holidays knows exactly what I am talking about.

My family and I do not agree on a range of topics, from gay marriage, to whether avocados are sustainable compared to cooked rice and spinach. Every dinner visit turns into the same battle of age-old wisdom and tradition versus the latest research.

My father is a bright man. He is a skeptic. As a Bengali immigrant working as an industrial engineer in the Soviet Union during the 70s, he grew up with communist ideals of hard work and collectivism, but was never a shut-away from the outside world either.

Each morning, when I used to wake up before the break of dawn to go to the washroom, rubbing my half-shut eyes still in my pajamas, I would find my father dressed and ready for the day. Sitting at the dining room table, listening to CNN in the background, and sipping his black coffee, he would go through stacks of newspapers that he picked up from our doorstep.

He talked about radical voices like queer, religious reformist Irshad Manji before I even did. He could even tell which Lady Gaga chart-topping hit was playing on the radio.

“Do not believe all the research you see in the media,” he would say looking up from his half-moon glasses while reading his third newspaper of the day, as he dog-eared a passage he planned to come back to later.

I found that statement outrageous, almost angering.

As a millennial, I was exposed to many more forms of media and scientific information than have ever before existed. My newsfeed and inbox were subscribed to updates from Scientific American, The New York Times, and the latest health blogs. In addition to living in Canada, known for its values of freedom, equality, and our good-looking, liberal Prime Minister, I felt that I was socially aware (or as my generation calls it, “woke”). I trusted my news sources and my research to corroborate what I read.

Could it be that my father, a PhD holder, a man who built a hospital and ran two businesses, was that ignorant? Could his years of life experience be discounted?

There are times he was right. For example, when the turmeric milk fad was out, I was one of the first in line at Starbucks to get my hands on it for its numerous health benefits. My father pointed out that turmeric had already existed in traditional Bengali cooking, and maybe if I looked through our kitchen cabinet I would find it along with some coconut oil that I spent my whole childhood avoiding until the internet told me it was the best thing ever.

There are times I questioned his opinions, like when it came to choosing a career in the growing fields of digital media, advocacy, and art; these were outside the traditional choices of becoming a doctor or an engineer that generations of my family had mapped as the only paths.

However, in the new age of fake news, alternative facts, and idealogical divide, we are left to distrust science and the media. Misinformation about facts, such as, placing even global warming science into question, makes it harder for us to have our own informed opinions.

Being stuck between ideologies of East and West, liberalism and conservatism, modern or traditional, how do we distinguish who is right? How do we get to the actual truth?

It wasn’t until my brief experience of entering the world of journalism as both an Elephant Journal apprentice and as a medical writer, that I realized there was merit to my father’s words about skepticism, and a way out of this confusion.

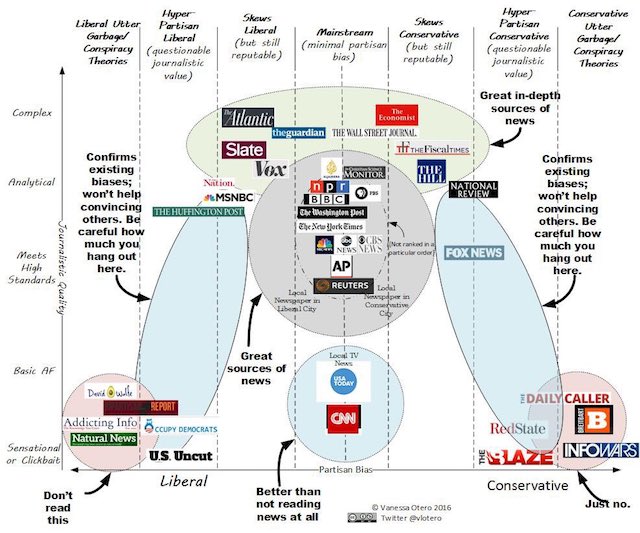

During my time at Elephant Academy, I learned that social media filters news for opinions like our own, creating self-validating social bubbles that are not exposed to new information. Many media sources also filter news based on their political leaning. For example, Fox News (right leaning) or Occupy Democrats (left leaning) stand on opposite sides of the spectrum compared to more neutral sources such as the BBC or The New York Times. Even the most trusted of articles may sometimes skew facts, or exaggerate details for purpose of sensationalism or to be the first to break the news.

We must be critical readers—even on opinions that agree with ours.

Similarly, as medical writer, I was forced to face that even research cannot always be trusted. In my primary job, I was assigned to review all the latest medical research publications as they came out, and check whether they had enough impact to change medical treatments.

Not all research is good research.

Some studies are funded by big pharmaceutical companies or conducted by authors funded or affiliated with corporations trying to sell a trend or a procedure. Others are anomalies and contradict results from 10 years of similar studies in the field. My job was to go through hundreds of research papers and weed out the unbiased and significant ones, as well as statistically recalculate whether those were enough to replace existing procedures or treatments.

In both of those experiences, it was shocking to see that not all scientific research and news were made equal.

Unfortunately, few of us are taught how to distinguish between different media and research sources. The goal of media literacy is to help us find unbiased sources and dig past ideologies and trends to bring us closer to the actual truth.

Luckily, there are some guidelines for what to look for in unbiased sources:

Authors: We need to ask ourselves, “Who is writing this article or reporting this news? Are they a neutral party without an agenda, or do they have a personal bias?” It is important to do research on the author’s backgrounds and their credibility in the field.

Just because someone claims to be doctor or an expert in the field, with a simple bit of background research, we may discover some controversies or differing beliefs.

I remember a bookshop keeper trying to sell me a book on “stress relief” by L. Ron Hubbard. The name sounded vaguely familiar, so I googled the author to discover that he was the head of the Church of Scientology. While some may subscribe to his beliefs, they were not something that resonated with me.

Funders: We must look for who is funding a particular study or article. Is this a university, government, or a corporation? What is the reason behind them funding this information? Often research papers or sources declare their funders and sponsors.

An article on a website or magazine promoting the detox effects of a new supplement may portray only the positive effects if the magazine is funded by the manufacturing company or is making revenue from its sales (for example, health supplements in sports magazines). It helps to look at customer and professional reviews by external, non-affiliated, and unbiased sites to get the full picture.

Multiple credible sources: We cannot rely on one source of information. Oftentimes, news organizations report sensational yet unconfirmed news just to be the first to get viewership. Until many credible media sources confirm the news, we cannot be sure. In terms of research, we should read multiple publications, and long-term studies, instead of relying on one stand-alone finding that needs further research to be confirmed.

How many times do we click on the front page of Yahoo News to find a story about scientists finding a cure for HIV or our favourite celebrity couple breaking up, just to find out that those were false alerts, or just very small advancements? We must wait for multiple major news sources to announce facts, before trusting clickbait headlines.

Intention: We must question the intention of the source of the information. Is the intention of this research to sell something or promote a political or personal agenda, or is the intention to benefit and care for the public?

Good sources care for the people’s right to know the truth and provide well-backed facts.

This useful infographic can help us distinguish where on the political or factual spectrum news sources lie:

We, as readers, need to be more skeptical, and media literacy helps us make informed everyday decisions about questions like these:

“Is this new food trend good for me?”

“Is this the newest medical treatment safe?”

Oftentimes, sensational news and numbers may be appealing, but we need to learn to dig deeper behind that information and be our own investigators.

In my own life, it helped to distinguish between advice from the media, my family, or when to trust myself in making healthier and more formulated decisions.

With media literacy, we can gain new tools to develop our own independent thinking that we can take with us to our next family dinners.

~

~

~

Author: Robbie Ahmed

Image: Twitter/Vanessa Otero

Editor: Travis May

Copy Editor: Callie Rushton

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply