Snowflakes danced and swirled toward my windshield as we drove home from a dinner party.

Carol of the Bells” was playing on the radio while my five-year-old, Ethan, tapped out the notes on my headrest. Our boys were eager to get home to spend the night in their sleeping bags under the twinkling “stars” of our Christmas tree.

“Mommy, is this what Christmas was like when you were little?” I paused. My palms suddenly felt clammy as I gripped the steering wheel. “Do you mean the weather?” I asked in a controlled voice. “It wasn’t cold like this in California.”

“I mean, was it like this? You know, did you have lots of fun with your family?” He proceeded to define fun: presents, parties, chocolate fudge, and candy canes.

“Actually, it was fun,” I lied. “My mom and dad were divorced, so I got two Christmases.”

“Wow, you must have gotten lots of presents,” squealed my youngest, Trevor.

We stopped at a red light. Its rosy glow spread across the deserted street. Everything looked clean, whitewashed in the light blanket of snow.

“So you had two houses: one with Grandpa and one with Grandma and Auntie Erin?”

“Sort of. I lived with Grandma, Auntie Erin, and Auntie Jennifer.”

“Who’s Jennifer?” Ethan asked before I realized her name had escaped my mouth. It was the first time I had ever mentioned her name.

I tried to sound casual. “She was my older sister.”

“Was?” Ethan asked, puzzled. “What do you mean?” Before I could answer, he fired off a barrage of questions. Why hadn’t he met her? Did she look like me? Did she have any kids? Did she live too far away to visit?

I couldn’t think of an age-appropriate way to describe kidney failure and AIDS. “She was very sick for a long time.”

Trevor chimed in, “So the doctor gave her medicine and made her all better?”

“They tried,” I said. “The doctors worked very hard to help her get better. But she died when she was 20, a long time before either of you were born.”

“Where is she buried?” They were into anything that had to do with pirates, so the idea of places where things were buried intrigued them. “Auntie Jennifer didn’t want to be buried. She was cremated after she died.”

I pull into our driveway, turned off the headlights, and turned around to look at them. One wish swirled around in my head: Please, God, don’t ever let them lose each other.

I opened the car door and let the snow hit my face so they couldn’t see my tears.

When we got inside, Ethan immediately requested to see a picture of her. I pulled out a worn leather photo album I kept hidden in my desk. I had wanted to hide the sadness I had experienced from my kids, at least until they were older…at least that is what I had been telling myself.

I placed one son on each knee and tried to brace myself for what was inside. In a tone I would have used to introduce them to an old friend, I said, “Kids, I’d like you to meet your Auntie Jennifer. Auntie Jennifer, these are your nephews, Ethan and Trevor.”

We looked through the pictures from decades ago, while I thought about what it would have been like to have her there with us.

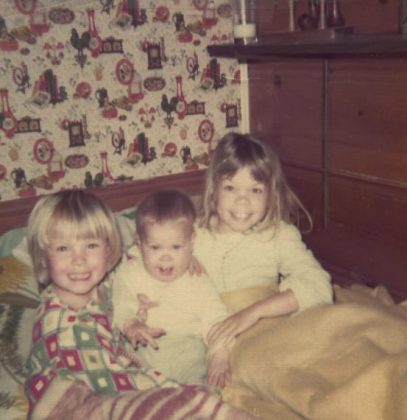

One photo captured Jennifer’s waist-length blonde hair blowing in the wind. She was 13, and despite her illness, she had a huge grin on her face. In another picture, I’m standing in between Jennifer and my younger sister, Erin. I’d almost forgotten I was the middle child: by the time I was 12, I was bigger and in a higher grade than my big sister.

I scrutinized pictures of myself at ages four and five, barely able to remember being that little girl jumping into an inflatable pool. I finally come to a picture of all three of us wearing our Easter best, looking completely dejected while sitting on Jennifer’s hospital bed after her latest kidney transplant.

“Mommy, what’s this one?” Trevor asked. It was my favorite photograph, taken in 1979: one of the few healthy years of her life. I was 10 and she was almost 14. It’s a sunny day in Southern California, and I’m holding a large ball, smiling up at my big sister. She’s looking straight at the camera, appearing wise and relaxed. She looked so real, I felt like I could almost touch her.

My boys continued to chatter, and I reflected on how comfortable they were as brothers. They interrupted each other, laughed at each other’s quirks, and fought over toys. I loved the normalcy of it all. I was also envious.

Jennifer and I could never fight because there was the danger that she might fall and have a seizure, or worse. The guilt and fear of those possibilities kept us from ever being close. And it made the hope of a normal Christmas that much more unattainable. Every childlike, magical thought I had of Santa coming down the chimney was overpowered by the fear that my sister would be taken away in another ambulance, perhaps never to be seen again.

I leaned down to kiss my boys on the top of their heads, breathing in the smell of their curly locks and feeling the weight of their warm bodies on my lap.

Suddenly tired and ready for bed, they crawled down and headed to the living room to arrange their sleeping bags under the tree. An unsettling question hit me: How the hell do I do I teach them to reach for the stars when I’m so tethered to memories fraught with grief and loss?

I breathed in, held my breath, and slowly let it out. I heard a voice in my head. Let go, Heather. It’s going to be okay. Just let go. It was Jennifer’s voice. I felt her with me, and somehow, I understood.

I didn’t have to be the best mom or pretend to be carefree. I didn’t have to hide the past from my kids. I owed it to myself to grieve all that happened and let it go. I stayed with my breath, repeating to myself, It’s going to be okay. Let go. As I said this, I sensed her arms wrapping around me, protecting and comforting me.

That night, my sons had helped me recapture a sense of intimacy with my sister that I’d lost. I silently thanked them and heard myself saying, I’m sorry I couldn’t piece you back together, Jennifer. I’m so sorry.

At that moment, I realized I felt responsible for not being able to help keep her alive, and I had never forgiven myself. I felt guilty that I grew up and got to attend college and have a family. Since I’d become a mother, I hadn’t acknowledged how trapped I felt. I had been keeping my past from my children while simultaneously trying to move forward. But I was always holding my breath, terrorized by the thought of losing my boys or experiencing that kind of trauma again.

When my boys quieted down, I trudged upstairs, pulled down the fold-out attic ladder, and rummaged around until I found my old sleeping bag. I dragged it downstairs and paused in the living room entryway, expecting to get a glimpse of their rosy cheeks as they drifted to sleep.

Instead, they turned their heads toward me, and without saying a word, one scooted over to the left and the other to the right, making room for me to take my place in the middle.

~

Author: Heather Prichard

Image: Author’s own

Editor: Brooke Breazeale

Copy Editor: Nicole

\p=-[‘]

Editor: lo9ol;/

Read 9 comments and reply