My brother made himself clear: no talking or writing about our past.

He didn’t want me to write about our lives, our childhoods, or our early adult years. Of course he didn’t: thick layers of sexual, emotional, and physical abuse are found there.

I didn’t want to remember it either.

I understand the fear, the shame. I know not everyone who faces traumatic events wants to face them. But I want to talk about trauma, to shatter the silence and help myself and others reclaim our sense of well-being and belonging in the world.

I promised him that I wouldn’t write the experiences that were his. But I had to write for myself.

I wanted to receive his blessing for my writing, but there was none—and there never would be. My brother took his life on February 6, 2018, validating my every fear.

Most of us that have experienced extreme circumstances and traumatic events have felt, at some point, like we could never turn toward them. Yet, some of us find a way to heal and grow from these things. Experiencing growth after trauma doesn’t mean you didn’t or won’t continue to suffer, but it could mean that all that abuse, trauma, and pain could all be in service to something good.

This idea of positive change coming about as a result of struggle with a major life crisis or a traumatic event is what is known as post-traumatic growth. For 20-plus years, I had no idea that there even was such a thing.

So how do we start on a path of post-traumatic growth in the aftermath of pain? I for one initially tried writing as a way of healing. The truth was, it went terribly. I couldn’t write the actual words down. I couldn’t stand to see the stories on paper.

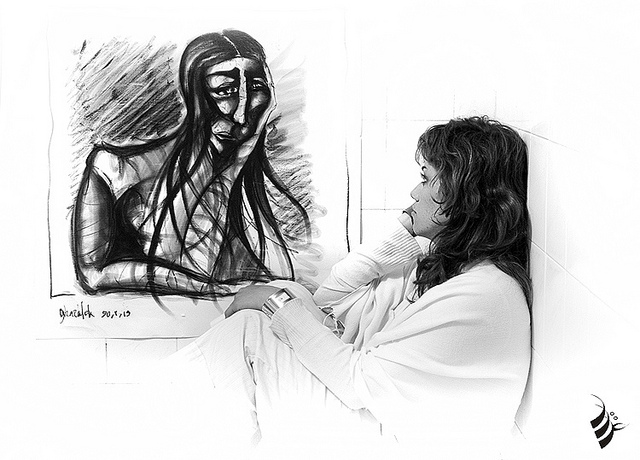

I needed help, and soon found an organization called the Million Person Project that helps people around the globe tell their stories. I learned a process that involved drawing pictures and creating icons that represented memories rather than writing down words. It took me years, but what eventually emerged was a visual map—a story that I had to uncover and own—just for me. This is a critical first step in the path of post-traumatic growth: being with your own story, hearing it from yourself first.

My icon imagery helped me connect with the pictures I held in my head. Over time, I was able to write vignettes of memories…

By the time I was five years old, I knew sexual and physical abuse. Back then, I knew my own body as something that wasn’t safe, and I knew that adults were not a source of safety and love.

By the age of five, I knew: I was on my own.

By the time I was six years old, I knew death. My 14-year-old brother Mark died after a lengthy battle with Hodgkin’s disease. Shortly after Mark died, we moved from Omaha to Dallas. We never talked about Mark again. There were no pictures; it was if he never existed at all.

By the age of six, I knew: death is followed by immediate and permanent silence.

In the years that followed, I learned what a leather belt felt like across my back. I knew the powerful force and sting of adult hands, the heat and welts of belts, the choking, yelling, and the insults—and I would continue to experience a cycle of abuse and the traumatic aftermath for many years to come…

As I began to transcribe my symbols into stories I wanted to find others who, like me, were telling their stories in an effort to healthily integrate them into their personal narrative and to create positive change. I learned that my story is not my story alone: abuse is a story that belongs to so many more people than we want to believe.

In 2014, the World Health Organization reported that one in five women and one in 13 men are sexually abused as children. That means that more than 700 million females worldwide are subject to just this one genre of abuse—a figure more than twice the size of the population of the entire United States. For men, this statistic represents 300 million victims, or almost the entire population of the U.S.

When I truly grasped the statistical data (that is also grossly underreported) and understood that these events are commonly instigated by the people closest to the victims, I thought, “How the hell can there be so much abuse, violence, and trauma and still so much silence? Where are all of the stories? I imagine all of these voices will never be heard…what is at stake in all this silence?”

And while there remains so much silence, this silence, to me, represents the massive potential power to create change.

I refuse to participate in the silencing and stigmatizing of what is clearly a global epidemic. Silence and stigma are the drivers of denial and suffering. It’s clear that silencing yourself or anyone else is an isolating act; silence is the antithesis of connection, which is the very thing we need to heal, integrate, and create change.

Transforming trauma into positive change for good is a journey of reclaiming yourself and your life. It is the silence that kills. It kills part of our souls. Silence kills victims of abuse who can’t find a way out of the shame and self-blaming. I know that my brother could have found a path out if he had found a way to acknowledge his truth to himself. I know that we all will find a path out if we first acknowledge to ourselves our own truth.

Your truth really can set you free.

What I know now (that I didn’t know before I stepped out publicly) is:

1. Shattering silence shatters shame—and not everyone will like it.

Shattering shame means naming it, taking it out of the shadows and into the light.

When it comes to stigmatized trauma, we all carry both the initial experience of the abuse, and the ensuing shame about it. It’s normal, and the truth is there are so many more people who share our life experiences than we think, and there are so many loving people out there to help us.

When we’re isolated, we believe we’re alone in the world. Our silence breeds false beliefs that tell us we are worthless, damaged pieces of sh*t that have nothing to contribute to the world. That is not true. Your story is not yours alone; there is a massive global community of people out there who want to help.

2. Traumas and tragedies also hold the power to our greatest sources of transformation.

Judith Herman writes, “The knowledge of horrible events periodically intrudes into public awareness, but is rarely retained for long. Denial, repression, and dissociation operate on a social as well as individual level.”

In the United States, we live in a collective denial culture that dominantly promotes material and career success to the exclusion of genuine well-being within ourselves. As a result, access to the help we need is not so readily available; there is no emergency room for certain kinds of pain.

Pain holds a transformative power. Turning toward suffering is the foundation of almost every ancient wisdom practice known—and you must first be willing to turn toward yourself.

3. Healing is not magical.

There is no fixing; there is only integration.

There are real practices and routines—more than any one of us could fathom—that are meant for you and your unique path. These practices are a sort of spiritual gym where we rebuild ourselves, similar to going to the gym to work on strengthening and stretching our bodies to achieve our best selves (whatever that means for you). I don’t know if we ever fully heal, but we can certainly integrate our experiences. And when we do that, from what I can see, we start to live a life we truly want to live.

One practice that can be helpful for all of us is a simple breathing technique known as Coherent Breathing. Breathe in slowly for four seconds and then out slowly for four seconds. Start with five minutes each day, morning and night.

4. No one can fix you—ever.

No one has your answers; we just all have our experiences. No one can fix it for you. Nobody can “treat” a war, or abuse, or rape, or molestation—or any other horrendous event, for that matter. What has happened cannot be undone. When we understand and tend to our experiences, we develop the capacity to shine a light on a path for others still lost in the dark.

Your story can make a difference.

People who speak up about their traumatic experiences shatter stigmas and make it easier for those who are silent to compassionately examine—and maybe even talk about—their own experiences. Tell your story! Those impacted by traumatic events need to hear more of our stories, and most importantly, how we found our way back to ourselves and built a life worth living.

~

~

Author: Rachel Aidan

Image: GhazalehGhazanfari/Flickr

Editor: Callie Rushton

Copy Editor: Travis May

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 13 comments and reply