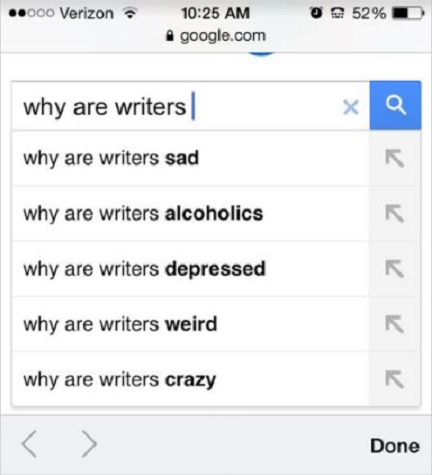

A while back, I jumped on Google to plug in a question I had about writers. Before I could finish typing the words, the search engine chimed in with the top results:

Why are writers alcoholics?

Why are writers depressed?

Why are writers crazy?

Why are writers sad?

Why are writers weird?

Great questions, Google. And way to nail my college years.

In that moment, I ditched my original search and fell down the rabbit hole exploring the link between artists and depression. I personally had always related to the idea of the manic, misunderstood artist. And as a writer who was put on my first antidepressant at age 15 after being admitted to an eating disorder treatment center, I was curious about the connection and intrigued by the “whys.”

Not surprisingly, there were many studies that made a strong correlation between the two. Nancy Andreasen and Arnold Ludwig and psychologist Kay Redfield Jamison are well-known for their studies on this topic. The fact that little research has been done to dismiss their claims also seemed to give their findings more support.

While there were several articles and studies linking creativity to mental illness, others challenged these claims as small, limiting, vague, and easily biased, stating that anyone and everyone who set out to prove artists were more likely to suffer from mental health issues would no doubt succeed in doing so. Many naysayers argue the studies seemed more suggestive than scientific.

The largest critiques came in the form of how we have normalized this idea and pathologized people with creative gifts. Most critics found it disturbing that we have collectively agreed upon the notion that creativity and anguish run parallel to one another. We no longer question it; we simply know it to be true.

Some studies were more thorough. According to CNN, one of the largest studies, led by Simon Kyaga, left few questions and had far less critics because of the number of people studied:

“Using a registry of psychiatric patients, they tracked nearly 1.2 million Swedes and their relatives. The patients demonstrated conditions ranging from schizophrenia and depression to ADHD and anxiety syndromes.

They found that people working in creative fields, including dancers, photographers and authors, were 8% more likely to live with bipolar disorder. Writers were a staggering 121% more likely to suffer from the condition, and nearly 50% more likely to commit suicide than the general population.

They also found that people in creative professions were more likely to have relatives with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, anorexia and autism.”

This stigma surrounding artists is nothing new. The age-old myth that creative genius and depression are interwoven can be traced back to many artists—painter Vincent Van Gough, writer Sylvia Plath, and more recently, musician Chris Cornell.

Some of the most iconic musicians, artists, and writers have talked openly about the link between sadness and heightened personal expression. In the last century alone, we’ve lost many of our right-brained masterminds at disturbingly young ages, and oftentimes by their own hands. Not surprisingly, it’s much more difficult to find artists who have not struggled with their psychological state than those who have.

Outside the hung jury of studies, my research led me to understand that most of us artistic types follow this creative path regardless, knowing it’s a higher calling. Many of us feel different, like we don’t quite fit in. And in our logical, linear society, this may also be why it’s easy to mindlessly place those who think outside the box, in a box, so to speak.

We also believe we’re here to benefit humanity by dissecting our own internal worlds and turning them into something tangible, relatable, and beautiful. We want to make people feel something, and our art is the vessel we use to accomplish this daunting task. No matter how painful it is for us to express, we cannot keep it inside of us, yet sadly, many of us seem to self-destruct at times.

It’s not always easy being plagued with a knowing that our inquisitive minds and soft hearts are the key to our genius. It may feel unfair that our insightful and empathetic nature is what propels both our creativity, and at times, our fall from grace. We see and feel things differently. Our inner world is complex, multi-dimensional, and isolating at times—and the only way to make sense of it is for us to create.

Many of us lead an unexamined life until our fingers hit the keyboard or our paintbrush touches the canvas. Our words, paintings, music, and stories are in some ways the projection of the deepest fragmentation of who we are. Our art simply makes these hidden pieces come alive, because any form of art requires us to step outside the world we live in and into a deeper, more reflective part of ourselves.

Although the ability to empathize and feel deeper may at times come with the side effect of our highs matching our lows, this doesn’t mean we’re doomed to self-destruct or that our creative outlets need to be fueled by bouts of insanity.

Many of us come from broken homes or have had difficult life experiences. And while our art has, at times, saved us, internalizing that we must be damaged to be creative is dangerous to our well-being and even our creative process.

I used to think this way. It was by participating in Elephant Academy, a three-month online writing course based in mindfulness, where I learned that this way of thinking is not only detrimental, but also not always true.

When we give into this type of seduction and romanticize any form of misery associated with our creative process, we’re attaching ourselves to the idea that we must have chaos in order to thrive as an artist. And oddly, when I let go of the limiting belief that my words would only hit the keyboard if I was in a state of overwhelm, my writing not only followed, but evolved.

I discovered that the creative process and meditative process are not much different from one another. The book, True Perception: The Path of Dharma Art by Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, also helped me shift my limiting beliefs around needing to be in state of angst in order to create.

According to Rinpoche:

“Dharma art refers to art that springs from a certain creative state of mind on the part of the artist that could be called the meditative state. It is an attitude of directness and unself-consciousness in one’s creative work. We give up aggression, both toward ourselves…and toward others. Genuine Art—dharma art—is simply the activity of nonaggression.”

To create is to receive. There is no ego involved. When we’re open to receiving the work that is trying to express itself through us, relying on coffee, depression, or sadness to fuel our genius is no longer necessary and actually hinders our creative process in the long run. Our clarity and self-confidence should come from trusting that we are being trusted by a force greater than ourselves to bring our own unique expression into existence.

Yes, creativity can be elusive—especially when we’re afraid of failing at the work we know we were put on this earth to do. And while I’m convinced the stereotype of the unstable artist may never completely vanish, I do believe we can begin to transcend our reputation through educating ourselves, caring for ourselves, and believing that what we’re called to do creatively does not have to coincide with our demise.

If we can trust that what flows thorough us is bigger than us, and we’re simply the receiver of what wishes to come forth, our ego has no room to play. It’s no longer about us or our own worth. Because it’s not our job to judge what is begging to be expressed, it’s our job to listen, let it take shape, and give grace to ourselves in the process.

We don’t have to become our own scratching posts in order to live a full, grounded, creative life. We don’t have to resonate with the mad genius or broken artist in order to realize yes, we may feel different, but that this feeling is a gift and not a curse.

Our gifts shouldn’t cause us to unravel; they should encourage us—and the collective—to awaken and thrive. They should benefit everyone—ourselves included.

And if we believe, like most of us do, that any genre of art is a higher calling, it would only make sense that we would trust the process a bit more, knowing we cannot screw up what we were meant to do.

~

5 Mindful Things to Do Each Morning:

~

Relephant:

Beat Generation: Geniuses? Mad Men? ~ Renu Namjoshi

Entrepreneurial Depression: the Epidemic we aren’t Talking About.

~

Author: Rachel Dehler

Image: Author’s own

Editor: Nicole Cameron

Copy Editor: Travis May

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 1 comment and reply