Author’s note: I didn’t know much about Anthony Bourdain, but like many others, the discovery of his passing led me to read more about him and discover how prolific and generous he was. I’ve decided to share this article in tribute to him—to what he was trying to say, over and over that “often, [travel] hurts.” He nevertheless encouraged people to “get off the couch and move.” And just so it didn’t ring dead, he’d demonstrate solid poetic chops: “The journey is part of the experience—an expression of the seriousness of one’s intent. One doesn’t take the A train to Mecca.”

~

I’m almost to the end of my 10th year living outside the country of my birth.

A friend of mine and I like to participate in the endless argument about whether I should call myself an immigrant or an expat.

“Until I have another passport, I’m an expat,” I always insist.

A Peruvian in New York City, he has a passport—as sure as I have strained eye-rolling muscles. We have fun getting nowhere with this banter because we’re both a bit alien, and thus know full well the value of relating about anything. I’ve found that people who don’t live like us generally find the idea of leaving home fascinating, pointless, or a fickle combination of both.

I often hear people say, “You lead such an interesting life—amazing! I wish I could do that!” To this, I respond with a gracious, real-looking smile that fights with an inner voice shouting a caveat: “We’re all living with pluses and minuses, darling.”

I’ve been thinking lately: what if I let that response out, in a way that isn’t so utterly inappropriate and ungrateful-sounding? What if there was a way to explain why some of us fling ourselves off the coast of our culture into a massive sea of mixed societal norms? What if it was in a bulleted list of five FYIs? Hmmm.

Expat confessions:

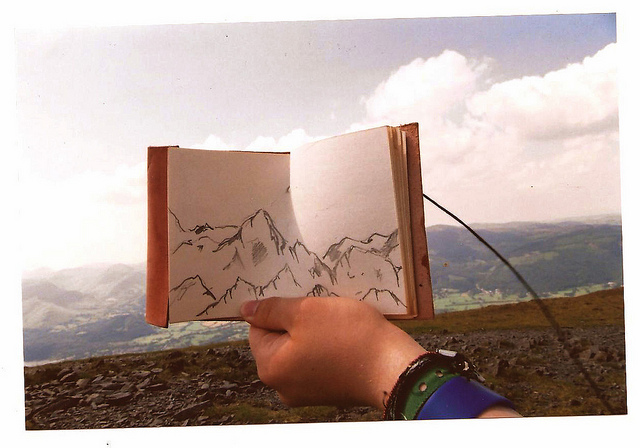

1. Living somewhere else is not the same as traveling.

I find it takes almost a year to reach a point where a place “penetrates” your identity. This would be the point where your old self starts to shift because you can’t retain two realities strongly at once.

I remember visiting New York City a year after moving to Doha, Qatar. When I went back to the city, I realized that I had forgotten some of the subway stops. I felt like I had dementia, because I had been so in sync with them when I lived there—down to knowing where on each platform to stand for what reason. Whenever I returned for a visit, I had to carry a small map of the subway system in my wallet.

Meanwhile, after over seven years living in Doha, I went from having a map of the city in the passenger seat to knowing all of the idiosyncrasies of traffic.

The same thing happened to how I navigated social situations. I forgot a lot about how Americans like to do things as I learned how so many other cultures perceived reality. I had to stay curious and open to this so I could navigate it with any efficacy. This is much easier said than done. And this has fundamentally impacted my identity.

2. Experience is not free.

The edginess of figuring out how, when, and where to go; the constant newness at the beginning; the language, culture, and mind-blowing moments of, as David Byrne would say, “How did I get here?”—all of these things replace a sense of simplicity inside. As the context around what we do builds, the frame around what we left behind disintegrates.

Our naïve view of life “as it is to be lived” vanishes, and this is particularly evident when things that used to be intriguing start to seem kind of trite in light of a new point of view. A huge gravitational pull toward cynicism forms in the vacuum left by what we used to love to do and think about.

It’s not as exciting anymore to walk down Fifth Avenue and window-shop at Tiffany’s. A favorite restaurant no longer delivers giddy joy when we take a seat. Sometimes, the places and things we used to love are not even there anymore! It’s like getting older in fast forward. We are challenged to get up and actually search for things that bring real joy because so much of what used to doesn’t anymore. (And yet, if we follow this instinct to search for those things, what we usually find is more aligned with our deeper sense: things that sing to our inner child before it was squeezed into social expectations.)

3. Alienation is something we are used to, but it still catches us off guard.

All of the people with whom we were once able to have deep and long conversations—no matter how close they once were—are gradually relegated to colleague status. The limit of what the expat can say is as clear as a brick wall in front of a speeding vehicle. And so we often prefer simple, slow chats or hyperbole and philosophy to meandering conversational voyages.

This is sometimes tiring. It lacks a sense of intimacy. We have gained the unassuming global perspective at the expense of the assuming local one, and we’ve learned to fashion an overcoat of coping mechanisms to warm ourselves in the cold of unexpectedly isolating moments. Depth of character, an agile imagination, and a sense of empathy become a mandatory requirements among close company.

4. We are generally more fragile than “rooted” people, and sometimes need to work hard just to feel balanced.

This is especially true when we travel from the country we are an expat in. It’s like a double exposure effect on a reality we are already working to sync with.

I once traveled to a European country for a long weekend from the Middle East, my home of five years at that point. I was with a friend who took me around to places and shared experiences of his everyday life.

There were moments in very ordinary scenarios where I felt completely disoriented. I didn’t want to take some behavior personally, but I didn’t have the skills to decipher where people were coming from. It was all happening so fast and frequently that I began to shut down and went into coping mode. It would have gone unnoticed by my friend if I hadn’t later participated in some drinking at a sizeable party he invited me to. I became so ungrounded that I suddenly trusted no one. Not even him.

Needless to say, it wasn’t pretty. I tried to open up, but he compared my experiences to his when he studied abroad, and this was a bit like comparing a calculator to a computer. We are still friends, but I will never be able to fully explain to him what happened.

5. With knowledge comes responsibility.

We’re living in a time where media likes to spin information. Reporting used to be based on who, what, where, when, and why. There was a kind of honor and simplicity to the system through which information flowed.

But it’s now way more complicated, competitive, and reactionary—if not theatrical. Perception is for sale. But once we actually get out of the bubble of our home country, or life as we know it, we see what is really happening on the ground. We have dinner conversations, gatherings, and even relationships with people from parts of the world that used to seem so dramatic.

We see that people are people, just like us. Stories are stories. Politics is politics. As the vague and contorted notions of life in foreign lands unravel with real experience, it’s hard to stay quiet in the midst of discussions so estranged from a more nuanced sense of reality. Expats have to choose battles and tune things out sometimes. It’s not always easy—especially with well-read folks who don’t get out of their towns and travel!

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply