An unforgettable, teachable moment in a New York public school.

Cobble Hill, Brooklyn was once a diverse neighborhood.

In the last several decades, the demographic of the neighborhood residents has changed drastically, however.

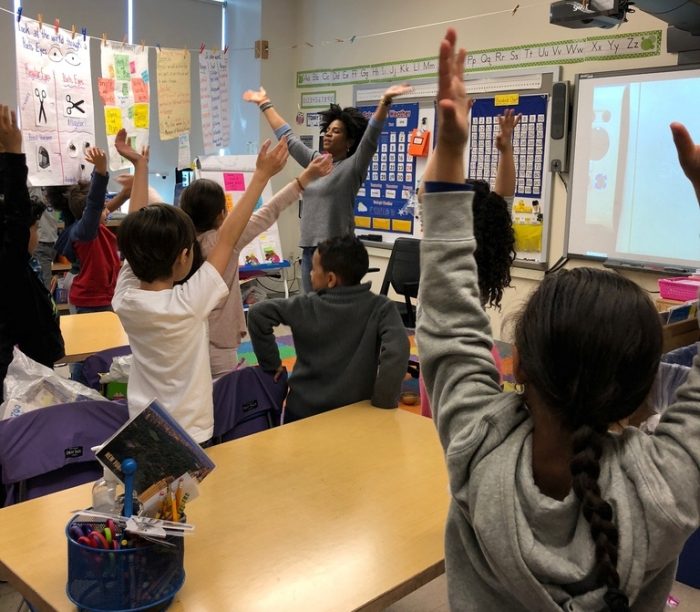

While it may be less apparent when walking down the street—because many immigrants and minorities still frequent this neighborhood to go to work as nannies, restaurant, and other local business staff—the reality of gentrification’s transformation of this neighborhood is remarkable when you enter one of the neighborhood schools to teach yoga and mindfulness there, like I do.

Of the six classes in which I teach over 150 children, I have counted a mere three African American girls and one African American boy in this beloved and fully resourced neighborhood public school. This year, I discovered there is at least one Indian girl as well, though from her presenting features, she could be Middle Eastern, Latin American, or even Native American, if I had to guess.

This year, I had a reflection-provoking encounter with her and another little girl while there to teach yoga.

On my third day of classes at this new site, I had been gifted with a kid’s yoga book called We Are All One by one of my students, whose mother happens to be the book’s illustrator. It is a great little story, full of colorful children playfully and harmoniously exploring yoga together.

True to the intention of yoga, the book emphasizes the fundamental yoga principle of union, or connection in its message. It also incorporates an interactive and flowing yoga sequence throughout so kids can explore the yoga postures described as the story is read aloud.

On the day I brought We Are All One to read to this mostly homogeneous community school in Brooklyn, the irony of the actual circumstances of many New York neighborhoods—that are in a state of gentrification and fall short of such intentions like community, equity, and justice—was not lost on me as I read these opening sentences:

“Have you heard the word yoga? It’s really very fun. It was started in India and means we are all one.”

Before I had even finished that last sentence, the little Indian girl blurted out, “Yoga is from India?!”

“Why, yes!” I responded.

“I didn’t know yoga was from India! That is where I was born!” She exclaimed with a burst of pride and a dimple-filled grin from ear to ear.

“Yes, sweetheart,” I practically squealed back with her infectious delight. “Yoga came from people who look just like you.”

There was a stir in the classroom from the other students and a few surprised stares, too.

“I never knew that,” she continued beaming. “My father didn’t tell me!”

“Well, where did you think it came from, my sweet?” I inquired.

“Uh, from America?”

Oh, what truth comes from the innocent mouth of babes.

A little uneasy, I went on to fill in the glaringly absent details that I neglected to convey more powerfully until this moment about yoga being a more than 2,000-year-old practice, and that we are all so lucky that East Indian people have generously shared yoga with us: a tool that brings us peace, health, and the ability to focus and connect more fully to ourselves and all around us.

I shared how new yoga actually is to America, though the people here who’ve seemed to take ownership of it are not its creators, nor its greatest experts. “We may have to go to the land of India to learn it best,” I boldly claimed, and realized the truth of this statement just as it exited my lips.

Still, the beauty and spontaneity of this teachable moment and its horror hit me all at once.

How is it that this little brown baby, who comes from India and lives in a neighborhood filled with yoga teacher moms and yoga studios, had no prior knowledge about the fact that these rich and empowering practices that we do together every week come from her people? (I later found out from her teacher that she and her brother were adopted from India.) How often in the past have I and other yoga teachers bypassed the honoring of the roots of and paying respect to this rich tradition and the people from which it comes?

The limitations and bias in yoga curriculums for kids.

When I’ve had the privilege of working as the yoga specialist in a school, whether I wrote my own curriculum, or was assigned an extended duration of the school year to teach my own yoga program, I made certain to dive into content on India as yoga’s birthplace.

But in recent years, much of my school teaching is sourced from other organizations and their curriculums, and I have not been consistent in teaching my unit on India that I once taught with splendor.

Moreover, in a thoughtful push to secularize yoga in schools in the spirit of respecting all students’ and their families’ religious and nonreligious beliefs, the removal of Sanskrit (and thereby its frequent references to Hindu deities) has had the adverse effect of eliminating the most obvious nod to the grand Indian heritage from which yoga comes.

Such a terrible loss, but is it perhaps a necessary one? I am not so certain because this cultural appropriation, this whitewashing of all things yoga is not okay, and especially not for our vulnerable black and brown kids.

Representation creates perception.

There is a profound inner expansion in the body, heart, and imagination that occurs in a child’s sense of what’s possible when she connects with the very real and important contributions that have been added to the world’s wonders by the likes of herself and her ancestors.

I saw it in my student’s face that day, and I observe it in the way she now grabs a mat up front and center for every yoga class, always eager, smiling, and fully engaged in every lesson.

How many children—and humans in general—have been robbed of this kind of enthusiastic connection to a world around them because we only tell a single story: that whiteness is supreme, and white people are responsible for everything noteworthy or great?

Were you to Google yoga right now, the image results are absurd when you note that the word “yoga” actually means union. You would likely see images of skinny white women in contorted physical shapes, dressed in nothing but a bathing suit, expensive “athleisure” clothing, or in some cases, nude.

The mechanism that drives this perception of yoga affects every perception we have. Evidently, even the most sourced and “trustworthy” internet search engines of the world are biased in favor of whiteness and everything white. Wondering why there are no great stock photos of an Indian girl in a Western school classroom doing yoga in this blog post? When I Google “yoga” or even “kid’s yoga,” it is practically impossible to see any children, adolescents, or adult students or teachers of color—without changing the key words to “black yogis” or “Latino yoga,” despite the fact that there are plenty who exist.

Being seen and telling the whole story.

At the Cobble Hill school during that same week in another classroom, as I was setting up before yoga class started, to my surprise, one of the four African American students among the classes I teach ran up and hugged me when she saw me.

She looked me in the eyes, smiled, and said, “You look like me!”

I looked right back at her and we shared a moment of truly being seen. I nearly teared up as I hugged her back and said, “I know baby! I am so glad you noticed because you are beautiful.”

I am so grateful today to be reminded that living in a black body and teaching this brown yoga tradition is in and of itself a radical altering of that singular story about who contemporary yoga belongs to. The truth of yoga’s expansion into the modern world asserts that yoga belongs to all of us. But we—as yoga service educators—must do better about honoring yoga’s history and roots.

The time is overdue for us to share the more complete, diverse, and fascinating story of yoga’s evolution from East to West.

~

Read 15 comments and reply