One day, years ago, in a session with my psychologist, I was on a self-denigrating trip.

I was telling her that I didn’t get why I felt so terrible about things that, in the great scheme of the world, were pretty small and petty. Like, how could I possibly be depressed or anxious living in Canada as a white, middle-class person, when there were people starving, or people whose cities were bombed every day, or people without access to clean water?

She cut me off pretty quickly and said she didn’t care if other people had it worse—that didn’t make how I felt less valid.

Fast forward eight years or so and my wife says the same thing: “You get to feel how you feel.”

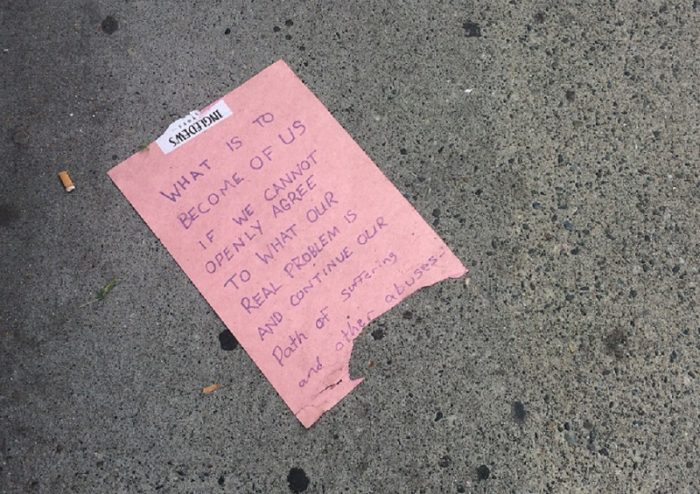

I’ve struggled with this for a long time, and I know I’m not alone in it. There is a sense that having access should mean we don’t experience suffering, or that our suffering is less worthy of being addressed. Yes, our personal situation could be worse and for many others it is worse, especially with the political climate in the dystopia that is the United States right now, but ignoring how we feel or labeling it as less legitimate isn’t helpful, or healthy.

Acknowledging that other people feel much worse has yet to make me feel better. If anything, it increases my personal suffering because I’m reinforcing some weird belief that how I feel doesn’t matter unless it’s bad enough—whatever that means. Instead of giving space to an emotion, I quash it, ignore it, and berate myself for it, as if it’s possible to switch my feelings off.

This doesn’t work. It never has and it never will. It’s also dismissive of my bodhisattva aspiration, which is to alleviate the suffering of all beings, a group in which I’m included.

Perspective is important, of course. First world problems, or bourgeois suffering, are things we can choose to let go of through comparison. If our biggest pain in the day is our grocery store not having our preferred loaf of bread or someone cutting us off in traffic, we could maybe pause and consider if it’s worth our energy to complain. But I’m talking about the legitimate pain of grief, systemic oppression, and the fear of the rise of fascism in America. These are very real forms of suffering that are absolutely valid and worthy of being addressed.

This may sound counterintuitive, or even contrary to what I’ve stated above, but one practice we can use to not minimize our suffering is to acknowledge that it does not make us special. This is to say, suffering is not personal, but human—acknowledging that suffering is universally experienced and equally worthy of being addressed, whether it is our own or others, is an acknowledgment of our shared humanity, regardless of background, embodiment, or economic status.

With this practice, I have been able to see how acknowledging my experience of depression enables me to show up and be present when a friend is experiencing depression. Or anxiety. Or overwhelm. Or any number of responses to systemic oppression and inadequate distribution of resources.

Suffering becomes less about “me” and more about “we.” Instead of wallowing in poor me, I can think about how my willingness to sit with how I feel, name it, and recognise it as human means I can be more effective in addressing the same suffering when it comes up for others. I see how, by showing myself care and kindness, I am more inclined and instinctively ready to offer the same to anyone I meet.

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply