A strange spasm of pessimism washed over my generation in the waning days of the 20th century.

Amid a strong economy and a global renaissance in democratization, we became overwhelmed with worries for the fate of the earth.

For the same globalization bringing greater prosperity and freedom was also revealing global environmental challenges for which few solutions were in sight.

We have a tendency to treat climate change as a proxy for a multitude of interlocking challenges, despeciation, desertification, rainforest destruction, and the death of the oceans. But there are actually several major, more human issues we tend to overlook here, like world hunger, state failure, overpopulation, and nuclear proliferation.

Together, they constitute a monstrous conundrum: humanity possesses neither the institutions nor the resources needed to grapple with a storehouse of troubles only a handful of people even recognize, leaving us to solve global problems at a local level; and yet, acting locally tends to inspire small-scale thinking—when what we really need is global thinking and action.

We have given little attention to the psychological impact of looking upon a world of troubles for which there appear no solutions, with the consequence of inaction being the fate of the earth. But it is almost certainly greater than we have hitherto imagined.

Environmentalists facing these threats often go through years of despair, while those who carry on are often plagued by an angst that never really passes.

A peculiar set of pathologies arise in the face of impossible challenges.

Organizations fall out among themselves, nations look for enemies abroad, and all too many simply drift into their own reality. Few reconcile themselves to failure while still maintaining a clear-eyed view, but this is required if we are to take on a world of troubles for which no solutions are in plain sight.

If people tend to shrink into pathological behaviors when confronting impossible challenges, then we need to worry about another global crisis that has gone almost completely unnoticed, and that is our own inner reactions to all of these external threats.

What happens when humanity looks upon the world and stammers over challenges for which it can imagine no solutions?

Stretch your mind as you may, the world will always remain too vast to compass. But it is simply inconceivable that a globally interconnected humanity might live sustainably on a planet of which it can barely conceive. Somehow, we are tasked with wrapping our hearts and minds around a world that will never fail to leave us overwhelmed.

Hence, it is of little surprise that, as everything about the world presses us closer together, the vast multitude seek retreat into smaller worlds: fascism, fundamentalism, nationalism, romanticism.

We run from what we cannot understand.

But if civilization is to survive, we must find a way to understand it.

It is the central paradox of our age, and the failure to solve it may spell our demise.

But in the end, it may not be our inability to solve these knotty conundrums that sinks us, but rather the way we react to our own shortfalls. For what at first seems impossible all too often turns out to be easy: we simply could not see a way forward until we dug a little deeper. But when we give up before we get started, escaping into a world of make believe rather than facing reality, everything tends to fall apart.

There are countless causes for the new rightwing authoritarianism, but our inability to face these massive global challenges—for which economic globalization and rising rates of immigration are simply a scapegoat—may be the most overlooked.

The real problem is not living with people different from ourselves, or financial insecurity wrought by global capital flows, though these may add to the burden of life in a complex world, but rather our inability to make sense of the world itself when our very survival depends on it.

Most every adult these days can conceive of the world as a whole, and some of us even identify with it more than we do with the nations of our birth.

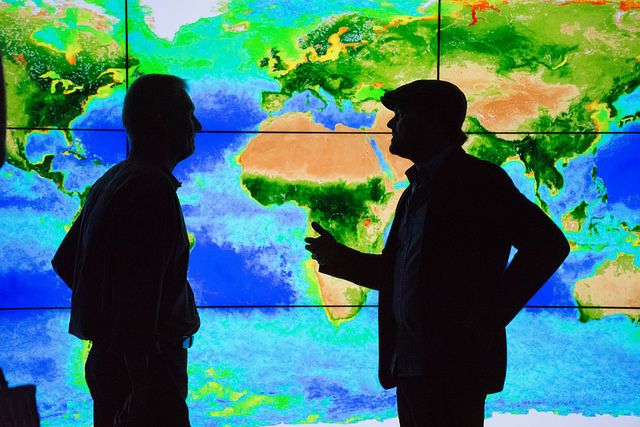

But few of us are capable of thinking about global challenges like climate change with the same kind of comprehensive balance that we apply to more national problems, like say the national debt or health care. There are just too many variables, contributing to too many ill affects, spread across too many places, and affecting too many people.

Thus, when we think about climate change, it tends to appear far too big to grasp; and in our failure to make sense of it, we come to treat it as an apocalyptic force over which we can exert no influence. It is the same with many global challenges, and all of them put together are all the more overwhelming.

If we are to live well in a globalized world, then we must learn to think globally.

Otherwise we will find ourselves continually confronted by problems we cannot understand, and the world will seem an incomprehensible mystery with which we cannot cope.

The retreat in the smaller world of fascist nationalism is merely a symptom of this bigger problem of living in a global civilization in which the greatest challenges we face are playing out on a far vaster and more interrelated field.

But if halting the regression to fascism requires that we think more broadly and feel more deeply for a wider range of beings, then there is a conjunction between our inner and outer freedom.

For defeating fascism may mean freeing ourselves from the grip of all the petty forces that keep us living in smaller worlds.

What is asked of us, in other words, is quite literally that we learn to live large, and, in so doing, open up the space in which others might do the same…until each of us learns to live well in the more rarefied air of a wider world.

If you liked this article, please check out my book, Convergence: The Globalization of Mind, and join the dialogue on Facebook.

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply