I dream of white sand beaches with palm trees stretching outward and diagonally.

You know, the kind in the pictures that bend so far toward the ground that you can almost sit perched up high on them.

“I think I’m going to take my college money and leave this place to go sell coconuts.”

The room filled with laughter.

I was serious.

But I didn’t take my college money and spend it on a plane ticket for a life of matted dreadlocks and bonfires. I stayed in college. I stayed because I wanted more. I wanted a sustainable life of travel.

And when I graduated, I traveled. I taught and I traveled. The new goal was to stay in a country long enough to actually get to know it.

What I craved wasn’t shallow relationships spent in late night hours in a hostel. I didn’t want a future of fake emotions ladened with copious amounts of alcohol, and dirty backpacks speckled with pot stains. No more guided trips to volcanoes or heavily rehearsed chocolate tours.

I wanted to know people. Real people.

So I left my country for a jungle. I left my family, my language, and my peanut butter at home.

My experience with leaving the nine-to-five behind has left me with the realization that there seems to be so little real information about what this lifestyle is like. There is this falsified idea that we can just let it all go and suddenly life becomes new and exciting. Which it does, however that does not mean it’s stress free and easy.

It’s not.

The life of a traveler is one of immense loneliness. It is the kind of loneliness that can only be understood by those who choose this path. It’s the hearing a bad song from your home country and finding yourself singing along kind of loneliness. Even in my short time on this journey, I have seen countless people try this lifestyle—only to give up on it, and return home within one year.

When I first left the United States, I remember walking the aisles of a grocery store desperately needing some kind of human interaction, and yet I couldn’t speak the language—I had nothing. I got to the cash register and realized that the people who bagged the groceries were speaking in sign language. I was overwhelmed with gratitude for the sheer fact that I could sign, “Hi, I know a little sign language. How are you?”

At night, I couldn’t identify the sounds I was hearing outside. And in the morning, I stared in awe as monkeys chased each other across tree branches. But that was it. Now what? What do I do without a car, or a friend, or even the knowledge of where to hike?

My perception before traveling was, “Well, I’ll just make friends. I’ll explore and try new foods. I’ll speak with all the people and learn their culture.” I pictured large families laughing around a table filled with frijoles y tortillas, old men telling me stories, and kids playing football in the tall grass.

No matter where your fantasy lies, whether it be deserted white beaches, lush forests, or snowcapped mountains, who you are will always be there.

I will always be there. Introverted with a history of alcohol abuse and starving myself. In recovery.

But solitude to an extreme can begin to take its toll on a person and not even the loudest howler monkey can out howl the voices inside my head.

We all have our demons.

The desire to control, manipulate, deny, or drown out the things we don’t like about ourselves. Whatever your poison, it will be presented in the silence of the night when the comfort of everyday life, and rituals, are no longer present.

And yet…

The life of a traveler is a high. It’s a fix that only a location change can medicate. Because eventually, you will find that trail, or that person who takes the time to speak slowly so you have a slight moment to connect, and you begin to learn the pieces that make the culture breathe.

It’s when your eating disorder gives up for a day and you finally try a buñuelo. When you make friends with a homeless man. When the guard knows your name. When you know that you can walk down that street safely, confidently. When yes, you belong here even if your work visa still makes you leave every 90 days.

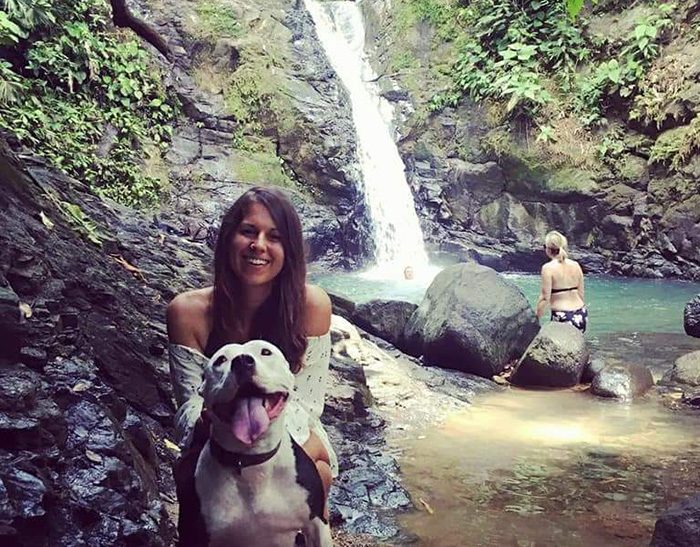

It’s taking a trip to a nearby country with friends who don’t know what you’re saying. Running races that you have never heard of. It’s when a kid talks to you and doesn’t care you have no idea what they are saying. It’s learning the language. It’s trying to learn the language. It’s hospital trips with a Venezuelan who lets you cry. It’s snuggling your dog in three different countries.

Is the travelers life worth it?

I don’t know.

How uncomfortable are you willing to be to in order to be comfortable amidst the unknown?

When Chula and I arrived in Panama, we had no one. She was my family and I was hers. She was a rescue dog from the States and it was time for us to create or own family from scratch.

It started out with us taking walks. We walked every night through the same neighborhood. Reggaeton and salsa were the backdrop to the sounds of croaking toads and buzzing insects. We learned not to trip over the cracks in the sidewalk and which areas were slippery death traps of moss.

Every night as we walked, we would pass by the same houses with the same families barbecuing or drinking cervezas. Eventually, people became curious of who the gringa was with her black and white pit bull or vaca. As time passed, these people became our new family in the jungle. I had a Columbian mom and a Panamanian father and sister. My other big sister, who made me vegetarian arepas down the street was from Venzuela. Better yet, her fur babies became Chulas best friends.

When I moved to the concrete jungle of Panama City, it was a little bit harder to become acquainted with people. Walking the streets no longer helped me connect as the people walked with their eyes facing downwards. In this case, I learned to frequent different places. I got a gym membership and always walked the same way to the same grocery store. That’s when I met my friend from those streets. My Spanish was getting better at this point but I was ecstatic to learn that he used to work on ships and had learned English. We had a unique friendship, but one that I cherish to this day.

Lastly, I didn’t give up my passion of running and I sought out communities who felt the same as I did about the love of the mountains. I started racing and seeing the different teams that were my competition. I used social media to reach out to the groups I saw and asked if I could run with them. I tend to be nervous and socially awkward, but that brave move is what gave me my Cutarra family, a kick-ass running team from Panama.

Traveling, contrary to what the glossy ads in a magazine tell you, is hard. It is especially hard when choosing it as an entire lifestyle.

Thankfully, the more I travel, the more I truly believe the world is innately good.

As I lay in my bed in this very moment, Chula asleep in hers, we await our Venezuelan family to return for the night in our Costa Rican home.

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 7 comments and reply