Awaking from my nap, I reached over to shut my alarm off and gasped.

I felt the air leave my lungs with a whoosh, and an expletive followed it. My entire back, emanating from a node of nerve pain, seized up. I couldn’t twist or bend without pain, so I just eased myself back into the bed, refilling my lungs with air as the initial shock passed.

Laying rigid, afraid to upset the spot again, my mind raced a mile a minute: I thought I was better. I thought with the months of doctors appointments, we’d fixed this problem. Why is the pain back?

When I finally risked standing up, the moment I straightened and put weight on my right foot, the pain surged and I fell back into the bed.

Dammit, this body is acting like it’s 93 years old!

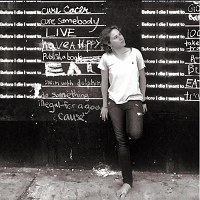

I’m only 23.

If you’re someone who lives with acute or chronic pain from an injury or illness, you likely know the “It’s better, no it’s not, wait it’s better again!” routine—very well. Recovery is even more challenging to navigate when an injury is invisible (either because it’s mental or the physicality is internal).

For outsiders, it’s confusing when someone who looks young and fit can’t carry the groceries, or needs to take a nap because pain has drained their reserves, or asks someone twice her age to walk slower because going faster causes pain.

When the realities of our bodies don’t meet others’ expectations, we must learn to consciously build up our internal and external support systems, educate others, and advocate for ourselves.

Some days, it’s just exhausting though. Pretending we’re well when we’re not is draining and constantly re-explaining our invisible situation is demoralizing.

It’s days like these when we must become our own best ally. Creating a reliable and supportive care team starts from the inside out. I’ve found that having a list of my holistic care routines handy helps me live more fully and authentically on the days when pain is present.

The list for living fully:

1. Room to grieve.

It’s not uncommon when we talk about our pain to hear people say, “But you have so much to be grateful for!” While this is true, it should not overshadow the reality that we need to grieve. Chronic pain or illness of any sort inherently implies a loss in your life—be it of work, energy level, self-image, or independence.

The tears of grief can heal and remind us what’s important so we creatively find new ways to live our life and meet our needs.

After grief, we can remember…

2. Gratitude.

One of my favorite ways to practice gratitude is with a body scan. When doing a body scan, you can start by bringing attention to the toes and then working upward to the crown of the head. As you breathe into each body part, notice it from the inside out. Spend a few breaths gently attending to each area like a nurse would a patient. Then, before moving the attention upward, express gratitude for that part of your body.

Once you’ve finished with the body scan, extend that gratitude outside of your body to friends, food, little moments that brought ease, and so on.

When you’re done, without judgment, notice how you feel after spending 10 to 20 minutes practicing gratitude.

3. Savor the slow.

One thing that’s becomes apparent for many with infirmities is the need to slow down. Some days, we may discover we simply can’t move as quickly as we used to, either mentally or physically. This limitation can either turn into a confining prison that we rail against, or can become our entryway to acceptance.

I find the slow days are a great invitation to be in tender relationship with things around me I would have otherwise missed. Savor easing out of bed instead of rushing; appreciate the slow arc of your cane as you walk. For every person who passes you, take the opportunity to send kindness their way as they speed through the day.

4. Advocate ahead of time.

Whether our impairment is new or old, speaking up when in need is hard. I’ve found myself biting my tongue rather than asking for help because shame, embarrassment, or a strong will gets in the way.

In the long run, this clamping down when in need rarely helps our recovery or self-image. We can help ourselves by creating two or three go-to phrases that we practice saying before a need arises. That way, in the moment, it’s natural and you don’t have to think about.

One of mine is: I would appreciate help (reaching the cereal), as my back injury doesn’t allow me to reach it easily. Keep the statements simple, clear, and dignified.

5. Find a window…

And chuck any linear goals out that window. Linear goals suck! It’s like we’ve created a mental graph, and we expect a line of improvement that is constantly soaring upward. Sometimes, we may not even realize we have this expectation of our recovery until we go crashing backward and find ourselves devastated.

Instead, set small daily goals that support gradual improvement with room for the entire recovery landscape, which includes unexpected ditches, steady plateaus, and spacious peaks. That’s a much more realistic recovery terrain.

6. Beware of isolation.

Mental health throughout recovery or maintenance is critical, but when an injury is invisible, isolation grows because people forget. They don’t have visible reminders of what we are going through.

Find ways to courageously bridge the separation. This may mean taking a friend to a doctor or physical therapy appointment rather than lattes, so they can support and understand more realistically our process. Maybe it means setting up a once a week check-in with a friend. It may also mean searching for an emotional support group or a sports club for those with disabilities.

Find ways to integrate your “normal” life with your “recovery” life.

7. Need versus love.

As we come out of our shells to interact with others genuinely regarding our illness, we must keep in mind that there will be times when we have a need a friend simply cannot meet.

There was a time I asked a friend to help me wash my hair, since I couldn’t do it on my own. She said no and I was absolutely mortified for asking. The reality though is that her response didn’t mean my need was invalid. My need was simply beyond her ability and comfort zone.

Know that “no” doesn’t mean you are unworthy of love or care. It will be hard, but keep asking for what you need.

8. Love yourself now.

It’s crucial we learn to be proud of our body now. The societal, familial, and personal expectations in our head that tell us, “But I should be stronger, faster, healthier,” are deeply ingrained. Comparing ourselves with others only causes suffering though.

We may not have tomorrow and each of us must live in our own body and mind. Ultimately, we choose the relationship and create the internal landscape.

You exist. Be proud now. Be kind now. Be love, for yourself, now.

Claim your inherent dignity, crippled body and all.

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 9 comments and reply