Once, I was at a football game with my older son.

My younger son was on the field. The spectators directly behind us were fans of the opposition and shouted insults at my son’s team during the whole game. We were wearing fan attire—they knew who we supported.

Sometime late in the game, I almost made a bad decision. I turned to my son and said, “I’m going to tell these people to shut up. Be ready to back me up if things go badly.”

My son replied, “I’m not backing you up if you do something stupid.”

It occurred to me then that the student had become the teacher—and that through our flaws, fathers can learn as well as teach.

Fortunately for me, on many other occasions, my sons demonstrated wisdom. Receiving it was both a joyful and humbling experience for me. As I reflected on where they learned it, I recognized many people were involved: their mother, their grandparents, extended family, and many others in our community.

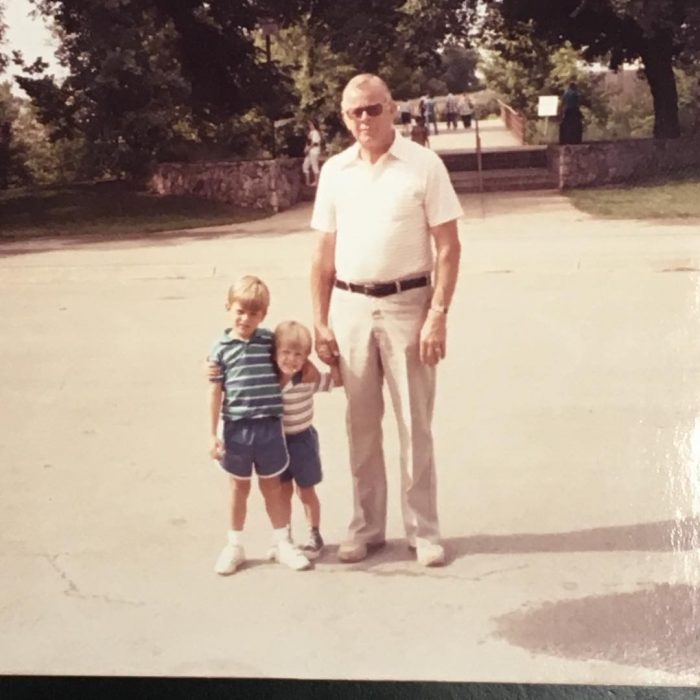

My father played a particularly important role.

When we think of someone who is sensitive to the needs of others, is affectionate, loves children, and is gentle, most of us probably think of a woman. And society in general does not value, as much as it should, nonmasculine behavior. The problem is “traditionally masculine characteristics may interfere with men’s relationships with others.” And that’s not good for our society.

But what if sensitivity, affection, love of children, and gentleness described our fathers?

For me, it does. My dad, whose family nickname was “Bud,” was a big man with a deep voice that was both soothing and authoritative. But, he didn’t use his physical stature to gain power over others. He was a gentle soul who loved children and squatted down when he spoke to them. He wanted to look them in the eyes to make them more comfortable instead of towering over them. That’s how he lived: looking people in the eyes and meeting them wherever they were.

This is a word picture of the man I grew up observing—the man I loved and respected. I wanted to be like him. Of course, he wasn’t perfect, and I don’t have a perfect record in applying the lessons he taught.

As far back as I can remember though, my dad has been a good example for me of one who demonstrated healthy masculinity. To me, healthy masculinity means using the God-given traits of men to benefit the world, not harm it. Unfortunately, not enough men have a built-in reference point for learning or understanding that.

Researchers have noted the importance of fathers passing down wisdom and love to their sons. Frank Pittman, M.D., in his book, Man Enough: Fathers, Sons and The Search for Masculinity states that for centuries, each generation of fathers has passed on less power, wisdom, and love to his sons.

“We finally reached a point where many fathers were largely irrelevant in the lives of their sons. […] Everyone seemed to be floundering around not knowing what to do with men or with their problematic and disoriented masculinity.” ⁓ Psychology Today, “Fathers and Sons“

My sons and I received wisdom and love from my father. Most of the lessons he taught through actions. On occasion, however, he taught with words. For example, when I was a teenager, some younger boys vandalized my car. I caught them and took them to the police. On the way, I berated them with profanity.

In talking to the police, the boys repeated what I said. The policeman, who knew my dad, repeated it to him. His response was typical of his teaching. He told me he I had to control my anger and there was no justification for the way I spoke to the boys.

“Remember this,” he said, “if you always act as a gentleman, you probably won’t have anything to apologize for.”

Through this incident, he taught me perhaps the most important lesson I learned from him—that, in everything, it was more important to focus on my conduct than the conduct of others.

We who have experienced the passing down of wisdom and love can draw from that in our roles as fathers—to love our sons well and to teach them what is important. We can affirm them so they don’t try to gain self-esteem through negative behavior, as too often happens.

Men who do not receive attention, affirmation, and love from their fathers tend to suffer from “father hunger,” and are waiting to be accepted by and treated with love and respect from them. Some of these men often become aggressive to prove their masculinity. They don’t treat women well, engage in materialistic pursuits in hopes of filling the void, and become “masculopathic philanderers, contenders, and controllers.”

In her film, “The Mask You Live In,” Jennifer Siebel Newsom addresses the struggle boys and young men encounter as they try to stay true to themselves while negotiating America’s masculine stereotypes that encourage boys to “disconnect from their emotions, devalue authentic friendships, objectify women, and resolve conflicts through violence.”

In examining this struggle, the film cites these significant statistics:

1. Boys are more likely than girls to flunk or drop out of school.

2. Boys are two times more likely than girls to be in special education.

3. Boys are four times more likely than girls to be expelled.

4. Every day three or more boys commit suicide, and it is the third leading cause of death among them.

5. Ninety-three percent of boys are exposed to internet porn.

6. Twenty-one percent of young men use pornography every day.

The film encourages us all to raise a healthier generation of boys and young men by changing our culture’s conversation about what constitutes healthy masculinity. Among other things, it calls us to:

1. Dispel stereotypical views that it is about physical force, sexual conquest, and economic success.

2. As parents and mentors, model a healthier form of masculinity and provide a positive representation of it that does not hinder social-emotional growth.

3. Help boys connect their hearts to their heads so they can find the courage and conviction to stay true to themselves.

I was fortunate to have this modeled in my home. My dad showed me that being sensitive, affectionate, loving, and gentle demonstrates healthy masculinity. He showed me to apply faith in one’s life by serving others, to be committed to family, and to treat others—all others, regardless of race, gender, religious belief, or other differences—with respect.

This was my experience. I realize everyone’s is different. So, this is a call for all of us to draw on the positive examples we have and provide a healthy view of masculinity to the boys and young men we can influence.

Deryl Goldenberg, Ph.D., in “The Psychology Behind Strained Father Son Relationships,” explains that men who have had unhealthy relationships with their fathers must resolve their unresolved wounds or their hurt and anger may transfer onto all their other relationships:

“The optimal outcome, as men move forward toward resolving their feelings with their fathers, is to no longer be entangled with them through anger or hurt. Men can bring their newly earned individuation and energy into their love life, work life and friendships with other men.”

I have gratitude for my dad and the role he played in my life. I’m not entangled with him through anger or hurt. I am attached to him in spirit, love, and positive memories. I wish that kind of relationship for all fathers and sons.

But, whether we had that example at home or not, if we each pass down what wisdom and love we have received, we can benefit the world—one life lesson at a time.

~

Read 8 comments and reply