Tuesday night is garbage night.

I hate garbage night. I hate the rocky rumble that I hear over the fence as neighbors roll their cans down to the street. The neighbors mean no harm at all. But, taking out the garbage was his thing. He took out the garbage. In fact, he took so much pride in his role as garbage man that he wrote a song about it. Not a Grammy award-winning hit, but a little jingle. He made light of garbage night.

So, now it’s Tuesday night again. He died on a Tuesday night. He died by his own hand on a Tuesday night. Tuesday nights are still brutal for me.

It took me months to be able to take out my own garbage. Not that I sat amidst heaps of stinking trash; I managed. But even the simplest act of taking out the garbage was hard. I rounded it up, pulled out those last rogue rolls of toilet paper (which really should be recycled), gathered from each can in the house—bathroom, kitchen, office, garage. Garbage duty became yet another grief-infused procession of plastic bags and tissues, as I blubbered my way down the driveway with puffy lips and red, tearful eyes.

Taking out the trash was one of hundreds—okay, let’s say thousands—of things he did. And when he died, I had to figure out how to reintegrate those thousands of things back into my life.

As a couple, we were among the rare tribe who lived and worked together. This is not uncommon for creative types. In our household, it was music.

We did everything together. We traveled together, socialized together, laughed together. We did things the way that I thought couples should do. In our marriage, we had the whole package. He was my best friend. My comic relief. My political sounding board. Business partner. Travel companion. Financial advisor. Handyman.

He was the one who ignited my mind at the dinner table, going into Jared Diamond’s theory of longitudinal effect on crop and migration routes. Or how Dvorak’s New World Symphony was inspired by African American slaves. And then, he’d do the small stuff—he’d do the dishes. He’d rake the garden. He’d fix the car.

The thing is, I let him be my everything. I let him be my knight in shining armor.

After all, wasn’t that the ideal love? Isn’t the dominant paradigm for romance, still, that we meet and marry The One?

Can we agree that the line “You complete me,” as haltingly delivered by Tom Cruise (now, a generation ago) became Hollywood gold because it spoke so directly from our fairy-tale longings of what love should be? Once upon a time, didn’t we, or don’t we still, all want to be “completed?” Moreover—let’s get real here—doesn’t it boost our egos just a little when we feel that we complete someone else?

These are intimate questions, but all of this came to light in the absence of my life partner.

“Let me check with Bob” had become the common refrain when scheduling, for example. I didn’t consider this strange or subservient to him. It was just the way that we were as a couple. (He would repeat the same caveat to his friends, only he’d say, “Let me check with The Boss”—and I secretly kind of loved that.)

But when he passed, I had to recreate my life. I had grown used to someone who was my Everything, and his death left thousands of empty holes, and a thousand vacant roles, to fill. I realized how good I’d had it, having found The One. But I also realized that maybe, it was time to reevaluate the ideal of finding the same “complete” package when it comes to loving again.

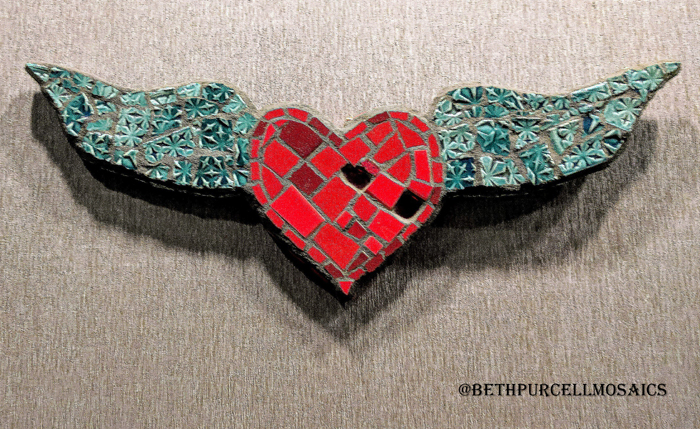

Thus was born my personal Mosaic Theory.

The mosaic, as an art form, is a whole comprised of diverse pieces. If it’s well-crafted, one or two bits could crumble, but the whole remains intact.

When my world collapsed into a pile of rubble, I realized I had to piece it all back together, and fill the holes my husband had left. I had to recreate the roles that he fulfilled—via the friends, family, support groups, and community who were most supportive. The Mosaic became a symbol for my new, pieced-together life, and I realized it’s actually something exquisite.

In reassembling myself, I am creating my own, new work of art.

The Mosaic Theory became my creed: Don’t hinge on one singular person to fulfill every need, desire, and interest that sparks my soul. Consciously integrate diversity, cultivate and preserve bonds with friends, family, community, to keep my life multifaceted. And if that one special person does come along, let that person become a part of the Mosaic I’ve already created—but not my entire tableau.

The Mosaic Theory created a way for me to cope with my husband’s sudden absence. I’d lost the best friend who got my quirky sense of humor; the one who inspired my intellect; the one who fixed the chicken coop door; the one I’d vent to after a bad day. Somehow, I had to patch all of those pieces together, given the resources at hand.

Naturally, I tapped into my extraordinary network of friends and family. I realized the richness that opened up for me when I called on diverse people to fill each role and empty hole. I cultivated deep connections with friends in many different groups and communities; and together, they create a magnificent montage.

In other words, through my loss, I found a way to complete myself—purely by virtue of the people and priorities I chose to piece back into my life.

My Mosaic Theory helped me expand my partnering paradigm and reevaluate the meaning of “The One” when I choose to love again.

Maybe, the next time around, it doesn’t have to be the same as it was before. Maybe, the business partner is different from the sexual partner. Maybe the one I laugh with the most isn’t my “partner” at all. Maybe the political rants come from one friend, and discussion about history comes from another. Maybe the person who fixes an electrical switch is different from the one who sparks my mind. Maybe, the one who I muse with about the origins of stars doesn’t have to be the same one I cuddle when night falls.

Taking a step back in widowhood allowed me to see that the Mosaic Theory is applicable, even to couples who are together. We can still make conscious decisions to broaden the many facets of our lives, and in the long run, our partnerships could benefit from that expansion.

This is not a call for isolation, or permanent solitude, distracted love, or infidelity. It’s just a healthy response to losing the person who I thought was my one and only. Whether we’re already in a committed relationship or marriage, or we’re single and ready to embark again, it’s important to integrate the pieces that fulfill us so that we can be whole individuals for our partners.

Turns out, my Mosaic Theory runs even deeper that I thought; it serves on a number of different levels:

1. It’s the antidote to the hard truth of impermanence—even in the very best of partnerships.

Widowhood came in my 30s, after we’d had 15 years together. So, at a relatively young age, I learned the crushing pain of losing a life partner. But, knowing I am complete in and of myself, is a tremendous comfort to shield against loss, in any form—and this applies to many circumstances, whether divorce, illness, or a breakup. The bitter truth is that we’re all temporary here. A multifaceted system of support can prove to be our saving grace if—or when—tragedy strikes.

2. The Mosaic Theory can strengthen an existing relationship, as it takes the burden off each partner to be “everything” for each other.

Often, in love, we stretch ourselves beyond our capacities. We want to provide for our lovers. We want to be everything, do everything, contribute, be the rock for the family.

But overextending can take a toll, and the disconnect between our will to perform and our sheer human limitations (and the essential need for self-care) creates friction. Over time, this disconnect can strain a partnership. If each partner knows and allows—or better, encourages—that some needs can be met outside the relationship, then the partners can steer back toward joy, and away from obligation.

3. The Mosaic Theory can guard against the dissolution of desire, when the original, sexy self is sacrificed for the all-in-one package.

When first love blossoms, the high of oxytocin might beckon us to put our own lives and routines aside, for the sake of bonding with a lover.

A typical sequence: Relationship starts. Lovers lose themselves in desire. Little by little, they mix their lives. Maybe “just this once,” one of them forgoes a weekly commitment so the couple can keep a date. Each person reciprocates. A sense of duty begins. One sacrifices his or her preference, so the two can attend events as a couple. Perhaps, then, friends hear more and more the regrets to invitations: I’m sorry, I can’t make it that weekend—(sweetie) and I have plans.

After a while, the bulk of activities are centered around this new, special someone. Only now, the someone is not so new. The love is still special, but the new has become routine. Days are filled with things done together.

The activities and friendships that each individual prioritized for self-fulfillment when romance began are perhaps now lower on the list—and yet, those were the very things that inspired each person at the start, and made the lovers so attractive to each other in the first place.

In her superb Ted Talk, Esther Perel speaks to how autonomy can bolster sensuality in relationships: “Desire comes with a certain amount of selfishness in the best sense of the word,” she says. “The ability to stay connected to oneself in the presence of another.”

She elaborates that in her research, the mysterious and elusive is what propels desire, even in long-term relationships. Individuals in vibrant, satisfied partnerships, cite radiance and self-confidence as key factors of appeal.

When we spend time with ourselves—comforting, loving, and befriending ourselves—after a while, our personal Mosaics become complete. Our lives have all the richness that brings out our best selves.

When we come to a partnership in complete wholeness, it is sublimely attractive. It is the whole person who is most compelling. In a healthy relationship, one person is attracted to another because they are desired more than they are needed.

Each person’s Mosaic can be a gift to a partnership, something to be honored and cultivated. But it takes work and communication to preserve a healthy autonomy. Narcissistic behavior, wherein partners subtly guilt-trip, or use passive-aggression and shame to steer activities (and lives) in one direction, does not serve the relationship. Instead, these patterns can build resentments.

Moreover, if the relationship fails, for whatever reason—be it death, divorce, breakup—it sets up an incomplete individual, whose wounds are fertile soil for the seeds of despair. The repair takes longer to heal, because the lives were so firmly interwoven. And the grief from the lost relationship can be compounded with a deep sense of unfulfillment in one’s core self.

Creating a complete Mosaic for myself, comprised of factors from more than just the sphere of my relationship, is the sweet spot for healthy love. This is the work of art I want to present to a lover, going forward.

These days, I pull precisely the right piece from my Mosaic for the specific moment at hand. Sometimes, I can comfort myself—and thankfully, I take out my own trash without the parade of tears. At other times, I know exactly who to call when I need business advice; which friend can share a good laugh; or which one has the patience to hear me gripe (yet again) about the news.

My new life may be rebuilt from fragments pieced together in the wake of tragedy. But each element—each friend, each influence, each source of inspiration—is carefully chosen, and the pieces fit together beautifully.

Fully assembled, they create a divine masterpiece.

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 56 comments and reply