Many sexual assault survivors, along with physical wounds, carry shame, self-hate, and an inability to discover healing.

Season 15, Grey’s Anatomy episode Silent All These Years focuses on trauma—to be specific—the aftermath of rape. In the story, a woman enters Grace-Sloan Memorial ER with severe injuries after having been raped. When the traumatized woman says she may have partially been at fault, a doctor asserts “You did not deserve this.”

Watching the scene, I wondered if it’s now okay to heal.

This is something I’ve been vlogging about on YouTube as a conduit between me and therapy. A recent post states It’s Okay to Heal. Obstinately, I’ve been arguing this assertion— me-with-me.

In therapy for over two decades, I hide from memories while also attempting to wholly remember, avoiding and seeking answers. This is the action of fatalistically begging PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) symptoms to become manageable.

Attempting to heal after a multitude of traumas that began early in childhood and continued into my twenties, has been a stutter-step; wanting to believe in and denying the possibility for recovery. One reason for this has been my intractable inability to accept a positive word during EMDR (Eye-Motioning Desensitization and Recovery) therapy.

As a learned and very talented therapist has motioned his hand in front of my eyes, I have been tasked with thinking about a trauma along with a word or idea that’s intended to replace the negative value that has circumvented my lengthy attempt at healing. The therapist and I have tried “You are a good person,” which continually tangles with historical self-hate tattoos, delivering a literal gagging-near-to-retching reaction. Second, we have attempted the more remedial, ought-to-be-easy, “You are okay.” This has engendered the oft-repeated reply “Clearly I am not okay because I cannot stomach the word good.”

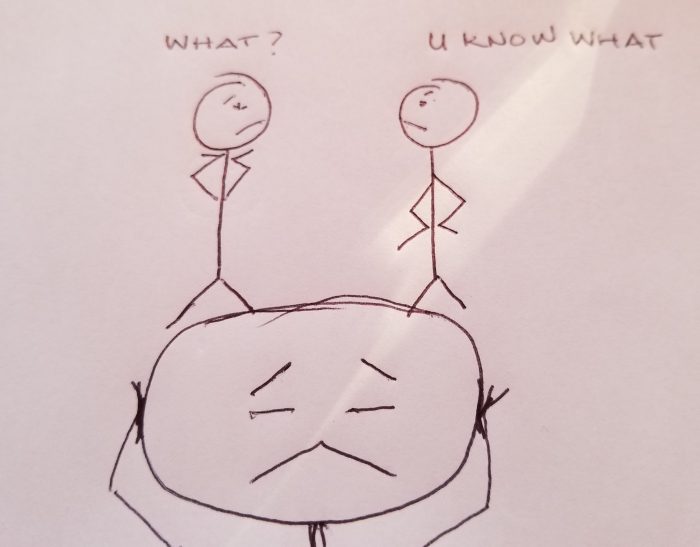

Hitting these two mind roadblocks leaves the therapist and I zig-zagging through a therapy desert, appearing to move forward but instead sidling left to right to avoid this mammoth mountain ridge of inner-loathing.

Many survivors, along with their wounds, carry shame, self-hate, and a denial of the ability to heal. Why this is can be intensely complicated.

Another person’s harm during a trauma, is ground into a victim’s brain in a particular way—leaving behind a residue that can be difficult to translate because it entwines with other memories.

How broken people raised me and subsequently-learned performance skills have continually insinuated into two-plus decades of harm. Everything wove together until child-thinking and societal “have to’s” such as “Be polite,” “Don’t tell,” and “You can’t say that” poke into adult-experienced traumas. Over the years, this survival-coping process knotted all the traumas I experienced into a rigid scar that cements my fifty-eight-year-old brain with the belief “I am bad.”

Perhaps, “You did not deserve this” offers an approach up and over millions of trauma mountain ranges of self-hate.

No one deserves trauma. Which means, neither do we.

Read 4 comments and reply