View this post on Instagram

I’m known as a “unicorn.”

It’s a moniker people have assigned to me as a term of endearment and a term of disdain, depending on their level of optimism at the time and subject of our interaction.

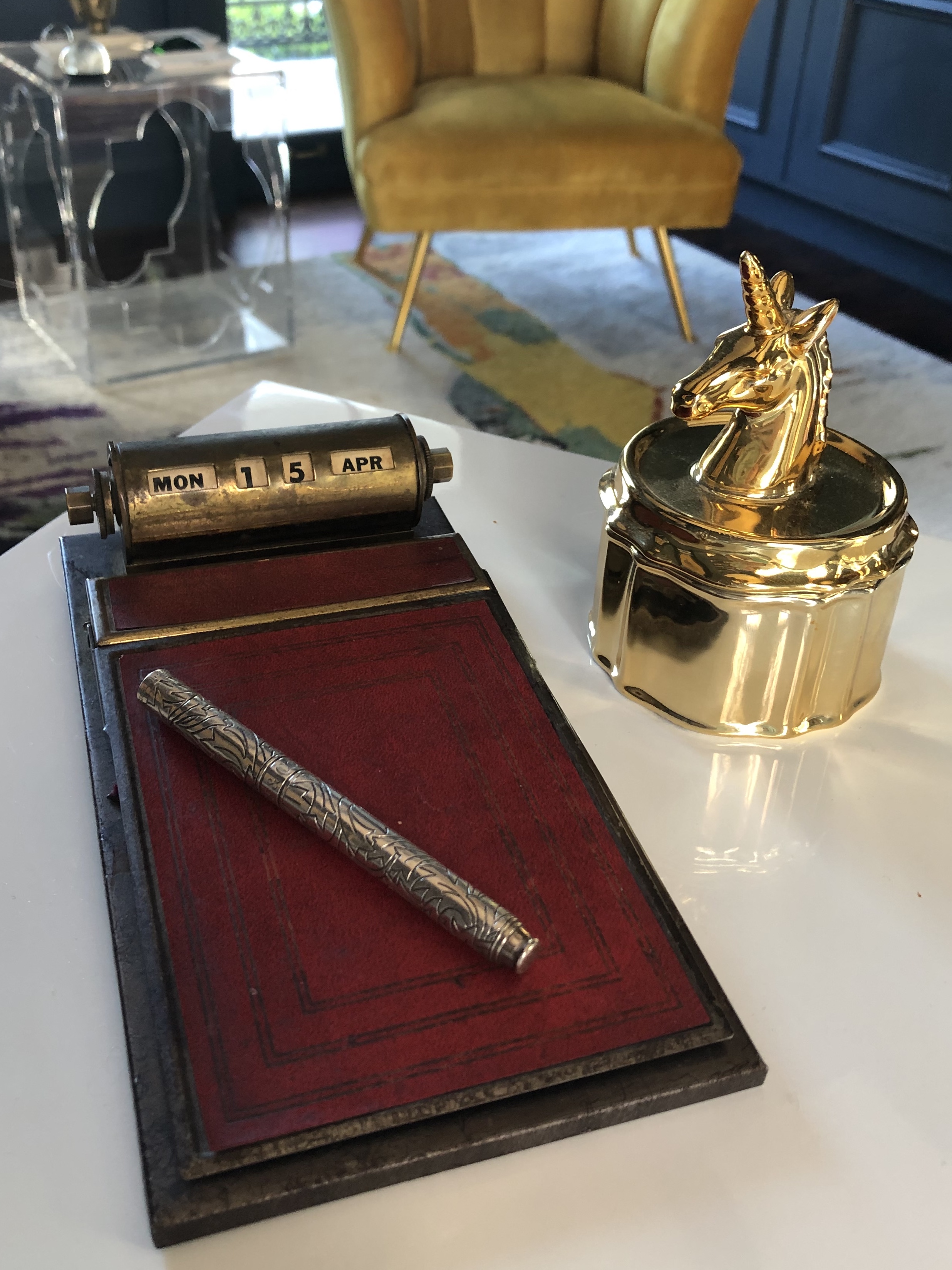

When I was a high school administrator, the positive use of the label manifested through thoughtful gifts of unicorn stickers, pens, desk accessories—signs of gratitude for our work together. Less-than-stellar labels surfaced through word-of-mouth, comments within earshot, and others relayed secondhand regarding frustration or annoyance with my perspective.

A few weeks ago, a unicorn-themed bakery opened in my hometown, Houston. I received several email and Facebook forwards sharing news of the opening—“I heard about this new place and thought of you!”

And while I know we label people and things for convenience, for an easy way to create boundaries to let people in and to keep them out, I also know that my nickname is not a label.

Unicorn is a verb, an active choice to respond productively to what life brings our way. For me, it is a mindset that stems from surviving a tumultuous childhood plagued with alcoholism, prescription drug abuse, and mental illness.

The traumas of my childhood are not unusual. No one has the monopoly on pain, but the universe blesses us in many ways, which for me included the seeds of an unwavering optimism from an early age. We cannot always control our circumstances, but we can work to channel our reactions into something beautiful, and if not beautiful, then at least productive. We can endeavor to bring this energy into the world.

The irony of my unicorn moniker is that I can only actively demonstrate it in person with friends, acquaintances, and strangers. In A New Earth, Eckhart Tolle referenced the challenges of living in the present moment with people you have known for a long time, especially family. It is hard to be like Teflon when a family member tells you, “You have been this way since you were five!” This challenge no doubt applies to me in other circumstances, but it is not the challenge I am referencing in this message.

The challenge is learning how to extend love while not subjecting yourself to abuse.

For many years, I thought being a unicorn, embodying optimism and love, meant having a higher threshold for attacks. I thought if the person is suffering, then I should be able to absorb the vitriol, the delusional threats. I did not realize the personal toll of the absorption and that acting as a unicorn involves loving myself before loving others.

Ajahn Brahm helped me from my dysfunctional thinking with his assertion, “To help someone out of a pit, I must sometimes enter the pit myself to reach for their hand—but I always remember to bring the ladder.” I can be in a challenging relationship when I have access to a ladder, but sometimes the suffering of others prohibits them from allowing the offer of this escape.

Non-unicorns often respond to these situations in frustration, a response that begets more pain with a viscous cycle of blame, resentment, and self-victimization. The unicorn approach in these instances is to use our ladder, but we exercise our ability to channel the pain to fuel loving-kindness. We keep our estranged loved ones near in our heart, intentionally sending compassion and love from afar.

As a unicorn, I am willing to jump in the pit, explore our interconnectedness, and help one another on our respective journeys. We long to have personal connections, to belong, but we must belong to ourselves first before we can give to another in the fullest sense.

Every day, I make a conscious effort to connect with the people around me.

How many layers do I need to peel back to find our similarities? I try to look cashiers in the eye and respond to their rote questions about my day with sincerity, asking them about their day in return. I try to let the anxious driver in my lane, offering a wave of understanding rather than a less-than-friendly gesture. And I pray that others are directly demonstrating kindness to some members of my family since I cannot. The power of loving the stranger has become even more important because of my isolation.

As an educator, I tried my best to deduce the reasons a student, parent, or teacher were acting far from their personal best. It was not unusual to receive a thank-you from a student after I assigned detention. On occasion, students would laugh and question why they expressed gratitude. I explained it was because they were polite and understood that even though there was a consequence, we had a good conversation about the situation. I tried to convey that there is not a clear right and wrong in the gray areas of conflict; rarely is there a true victor.

I recently published my first novel. A friend I have known since the sixth grade sent me a private message asking about the depths of pain the characters experienced, writing “that doesn’t come from an imagination.” She was correct; it came from personally experiencing intense pain. Through my writing, I am trying to use my experiences as a way to strengthen our interconnectedness.

More often than not, I am thankful for the pain of my experiences even though I find myself holding its weight every day of my life. On some days, the weight is like a wave; on other days, it is a few grains of sand stuck in my shoe, but I have learned to use the weight as a north star for spreading different forms of kindness into the world.

Pain can open us to compassion rather than resentment. It can connect us to others when channeled appropriately with a respect for ourselves.

Recently, my unicorn label surfaced in a lighthearted way. I agreed with the sentiment, but I also pointed out that unicorns have hooves firmly planted on the ground. Our optimism is not blind. After all, a unicorn is not a pegasus.

Read 2 comments and reply