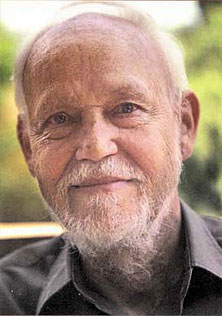

Every modern yogi and spiritual explorer owes a debt of gratitude to the late Huston Smith. May 31st would have been his 100th birthday. As a tribute to a great man, I’m posting here the obituary I wrote when he passed away in 2016.

A year that brought the passing of too many important public figures capped it off with the death of the past century’s leading interpreter of the world’s religions and the roles they play in people’s lives. Huston Smith died peacefully in his Berkeley California home, at age 97, on December 30, after a long, steady weakening that had those who knew him scratching their heads about how he managed to linger so long and remain so lucid. He was beloved for his wit, his decency and the joy he derived from good company and stimulating conversation, and he was revered for his unparalleled contributions to the study of spirituality and religion.

Born in 1919 in China and raised there by his missionary parents, Smith came home to America at 17 and pursued his studies in religion and philosophy. Always a self-identified Methodist, he was a spiritual explorer long before eclecticism became fashionable, and his investigation was never the kind of shallow pursuit he cautioned about; he famously compared spiritual dilettantes to people at a buffet who risk getting too much of what they want and not enough of what they need.

He plunged deeply into traditions other than his own, not just as a scholar but as a seeker of illumination. He practiced Zen meditation; he engaged in disciplines from the Sufi branch of Islam; he dove into yoga, famously bending and stretching his tall, lean body to demonstrate hatha yoga postures in a 1950s film that launched his public career, and again in 1996 on Bill Moyers’ five-part PBS series, “The Wisdom of Faith with Huston Smith.” By then, he was, as the Christian Science Monitor put it, “Religion’s Rock Star.“

The tradition that had the biggest impact on Smith, and by extension all of his readers and students, was Hinduism—specifically, the Vedanta philosophy whose essence is articulated in the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita. When I asked him how influential Vedanta was in his life, he was 88 and already frail. But he straightened up in his chair and his voice boomed “Immense!” As a young scholar beginning his first teaching job, at Washington University in St. Louis, he was advised by his new friend, Aldous Huxley, to look up Swami Satprakashananda at the local Vedanta Society. On his first visit, he purchased a copy of the Katha Upanishad. “I was overwhelmed in just two pages,” he told me, “astonished by how much truth could be compressed into so few words. I was hooked.”

He was tutored by Swami Satprakashananda for the next ten years. Those studies would inform the entire body of his work, which transformed the way millions of people understood religion, especially religions other than their own, and engaged their own spiritual impulses. Vedanta’s delineation of different paths for different personality types “came as a welcome revelation,” he said. So did the core insight captured in the Rig Veda dictum usually translated as “Truth is One, sages call it variously.” That perspective is known in scholarly circles as Perennialism, and Huston Smith embodied it in his life and described it better for laypeople than anyone, with the possible exceptions of his friends, Joseph Campbell and Huxley.

For advocating the underlying unity of the world’s religions, he was mistakenly accused of saying all religions are the same. This criticism ignores the distinction Smith made throughout his distinguished career—between the exoteric aspects of religion (rituals, forms, behavioral codes, stories, etc.) and the esoteric (direct inner experiences). “Exoterically, they’re very different,” he said, “but esoterically they are one.” That is, whatever pathway a seeker might follow, if taken to its highest level, he or she merges on the same mountaintop as travelers on other paths.

Huston’s seminal textbook, The Religions of Man (later retitled The World’s Religion), first published in 1958, reflects that point of view. It was also unique in its day in that it took religion seriously. Scholar of religion Dana Sawyer, the author of an authorized biography of Smith titled Huston Smith: Wisdomkeeper, says, “Rather than trying to explain religion away, as so many of his colleagues did in the 1950s, Huston claimed the right to love what he studied. . . . By emphasizing the value of religion rather than its drawbacks, and by describing the religions in ways that their adherents could recognize, Huston opened fresh perspective on religion.”

The book was a landmark. Sawyer explains: “To treat the religions as equals was unusual, since there tended to be a Christian or Western bias at the time. When they were treated as equals it was as antiquated curiosities, all equally useless, not as relevant sources of wisdom.”

Smith never stopped exploring and advocating, through his many books, media appearances and countless lectures around the world. His was a sane voice against fundamentalism and religious extremism, and for pluralism (he helped get the Dalai Lama into the U.S. for instance). In the 1960s, already famous, he took part in the psychedelic experiments of Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (later Ram Dass). He was considered the grownup in the crowd, warning against the cavalier use of drugs and pointing out that the goal of spiritual experience was not just altered states but altered traits.

It is not an exaggeration to say that Huston Smith’s fingerprints are on the progressive changes in how we in the West have come to approach spirituality. As one who was charmed by him in two memorable encounters, profoundly instructed by his work and honored to have him write the Foreword to one of my books (American Veda), I join his admirers and loved ones in celebrating his uniquely significant life.

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply