A man I once loved committed suicide.

I don’t say that for shock value; in fact, we need to make the conversation about suicide more normalized and less shocking. I used to be unable to speak about it—I couldn’t say the word suicide out loud. There was so much shame around the idea that my boyfriend, whom I’d loved, took his own life.

Much like many teenage relationships, ours was magical and all-consuming. He was beautiful and naturally cool in a River Phoenix 80s kind of way. He was street and book smart, fit in with every crowd, and was musical and artistic. And he loved me.

He first began showing signs of paranoia when we were 18. I moved in with him directly out of high school, and I honestly didn’t know the difference between relationship problems and burgeoning mental illness. This was 1988, before the internet, and such things were hard to talk about with friends and even harder to research. I would’ve loved to have had the option to Google in the privacy of my bedroom or on my phone.

As his illness began to take hold, I retreated to the comfort of alcohol, drugs, and food, which didn’t help. My normally peace-loving boyfriend began to act increasingly paranoid. We’d have horrible fights. I’d leave or he’d leave.

Once, he had to be hospitalized.

When I visited him in the hospital, he was talking coherently once again, his voice slow and careful, thick with tranquilization. He told me he didn’t like his brain all foggy. He felt like his body no longer housed his spirit.

The relationship never went back to the way it had been.

When someone we love’s mental state dramatically changes, it’s a hard thing to reconcile. We feel so helpless yet want to stick by them and be a support system. Sometimes, that’s appropriate. When it’s not, it’s time to make the tough choice of letting them go. His problems were way beyond my comprehension and the scope of my 22-year-old self. After six years of love and tears, I let him go.

He called me one night from a halfway house where he was living. I couldn’t find any words to say but I was happy he was safe.

Unfortunately, that was where he ended his life.

I woke up at a friend’s house to a call from home. In a private corner, I picked up the phone. I shut down as soon as I heard the words—the voice sounded far away—and I learned then that he had taken his own life. I couldn’t fathom that he was gone, the extreme effort it took to accomplish his task, and the pain his family would always feel—the guilt I felt.

A peek into his state of mind at the time came from his friend who spoke at the service his family had to celebrate his life. She said he’d related to the song “Big Empty” by Stone Temple Pilots, especially the lines:

“Too much walking shoes worn thin

Too much trippin’ and my soul’s worn thin.”

I understood that he didn’t feel like himself anymore. The struggles in his head were exhausting.

Suicide is complicated. It’s unknowable. When it happens, those closest to the victim can have a myriad of feelings: confusion, hurt, guilt, anger, and devastation. If they have left a note behind, it can lead to some answers (see the Netflix series “13 Reasons Why“), but most people don’t bother to explain how and why they’ve succumbed to the most desperate of actions.

According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention:

>> Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States.

>> In 2017 47,173 Americans died by suicide.

>> Also in 2017 there were an estimated 1,400,000 suicide attempts.

I alone have had one boyfriend, two friends, countless friends of friends, and many celebrities I’ve respected and admired (Anthony Bourdain, Kurt Cobain, Chris Cornell, Hunter S. Thompson, and David Foster Wallace, among them) take their own life unexpectedly.

Suicide stems from depression or other mental illness diagnoses. Sometimes the depression is internalized and suppressed, “But he/she always seemed so happy!” or exacerbated by the use or misuse of alcohol (a depressant), and there are people who’ve died from long-term alcohol or drug abuse. In recovery, we call this a slow suicide.

Then, there are suicides that are a result in whole or part from bullying, such as young people in the LGTBQ+ community who have been persecuted to the point of despair.

With mental illnesses such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, it becomes even more complicated. Bipolar individuals have manic and depressive states that make them feel so much that in comparison, they don’t like the dulled down life on medication. Or perhaps they aren’t on the correct drug or dosage that would give them the best quality of life.

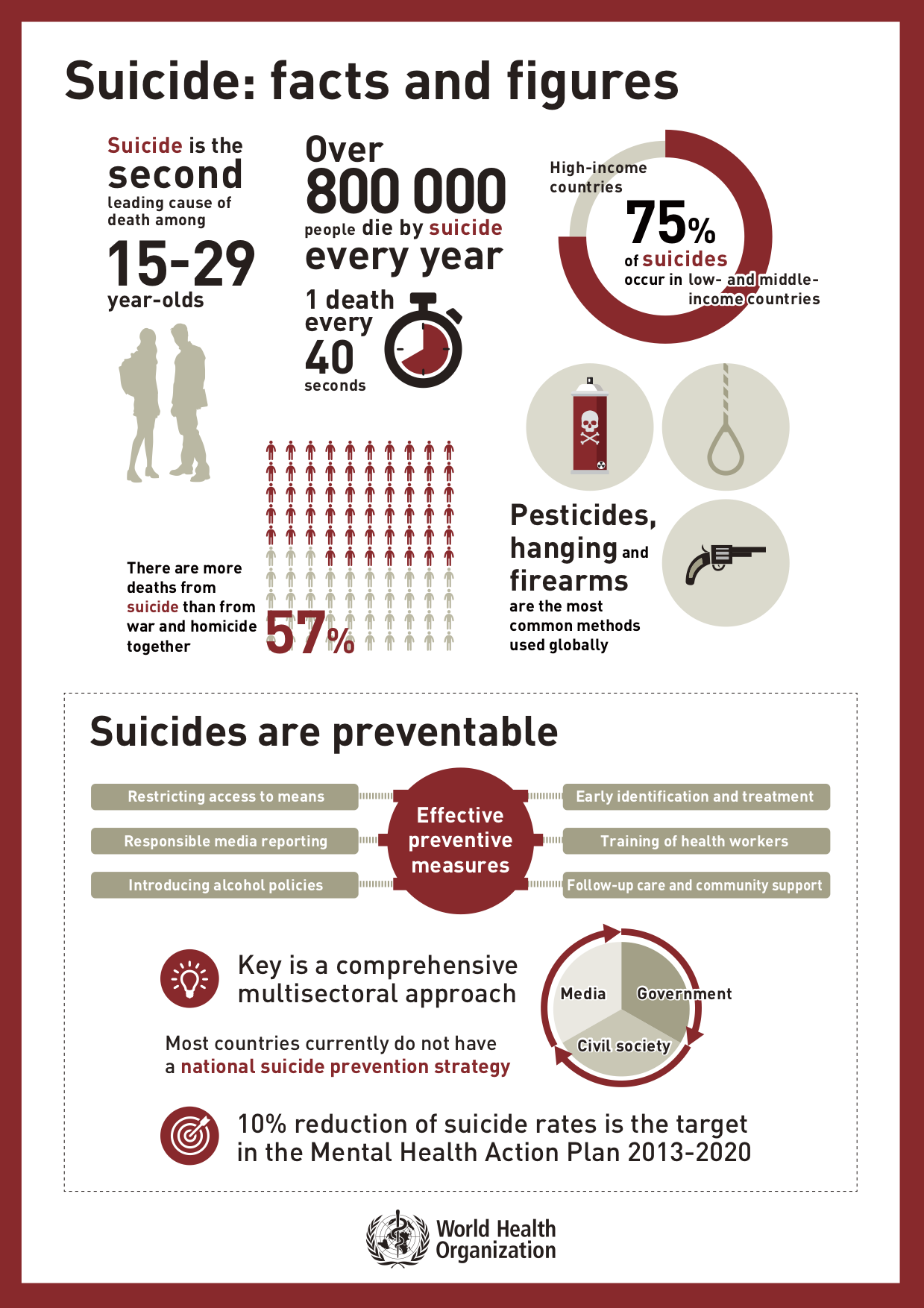

Suicide is the second leading cause of death of individuals ages 10-34 and the fourth leading cause of death of individuals ages 35-54.

Suicide claims more lives than war, murder, and natural disasters combined.

“Although suicide can be contagious, resilience can also be contagious.” ~ Mark Sinyor, MD

Sometimes, we need to seek outside help. I know I did. When I was in my late 20s, depressed, and not ready to face my alcoholism, I sought out a therapist who specializes in EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing).

EMDR stimulates the part of the brain that stores trauma and helps to neutralize the physical feelings that the body creates for protection. This type of therapy helped me to process the relationship and its tragic outcome in a short amount of time, with minimal talking.

The end result was that I could now talk about my relationship in a more open way, and no longer felt a knot of shame when someone mentioned his name. It still wasn’t easy to talk about, and I still felt confused as I was sad he was gone but glad he was no longer tormented. The therapy helped my body to turn off its flight-or-fight response. I could finally mourn the loss of our love.

I began to heal.

Nearly 90 percent of people with clinical depression can be treated successfully with medications and psychotherapy done together.

Shortly after my EMDR therapy, I participated in the “Out of the Darkness” Overnight Walk in New York City, where I lived at the time. The goal of the walk was to raise awareness about depression and suicide and honor those we had lost.

I walked from 8 p.m. to 8 a.m., 16 miles through the streets of Manhattan. The fundraising all went to suicide research and prevention. Instead of being a sad, somber walk, it was filled with stories, hugs, and laughter. It ended after the sunrise, where we all lit candles inside bags decorated for our loved ones. It was there that I discovered the power that comes with bringing suicide into the light.

We can destroy the stigma of depressive illnesses that can prevent people from getting help. When we become willing to talk openly about depression with our family and friends, we’ve done the first step toward suicide prevention.

Let’s keep the conversation going about suicide and depression. I know it’s uncomfortable. I know we don’t want to, but we need to. Our lives depend on it.

~

“The bravest thing I ever did was continuing my life when I wanted to die.” ~ Juliette Lewis

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 21 comments and reply