View this post on Instagram

A few nights ago, my girlfriend and I had a friend over we hadn’t seen for some time.

Our friend told us that she has not meditated in almost a year.

Knowing her to be a life-long meditator, I inquired as to why she stopped, and her answer did not surprise me. Not because I expected it of her, but because I have lost track of how many times I have heard this story from fellow meditation practitioners.

It also happens to be my story.

Kriyas

In my fifth year of meditating daily, something shocking began to happen. Wild and often disturbing bodily movements arose spontaneously.

Kundalini yoga experts call these spontaneous movements kriyas. Such movements often arise in yogis during intense meditation practice, and are regarded as a natural and healthy process associated with cleansing the body. (If you want to know more: Kundalini Vidya.)

Some of my kriyas looked like small tics we might normally associate with Tourette syndrome, while others were severe enough to physically throw me off my meditation cushion (a metaphorical command, as I would later come to realize). While these kriyas were intense, some did not frighten me, while others did.

Other movements indicated the need for specific action. Some would cause me to stretch an arm out as though reaching for something, while others caused me to hit myself in different ways. The latter type began to disturb me. They arose in conjunction with sharp experiences of shame and fear.

The Five Sheaths

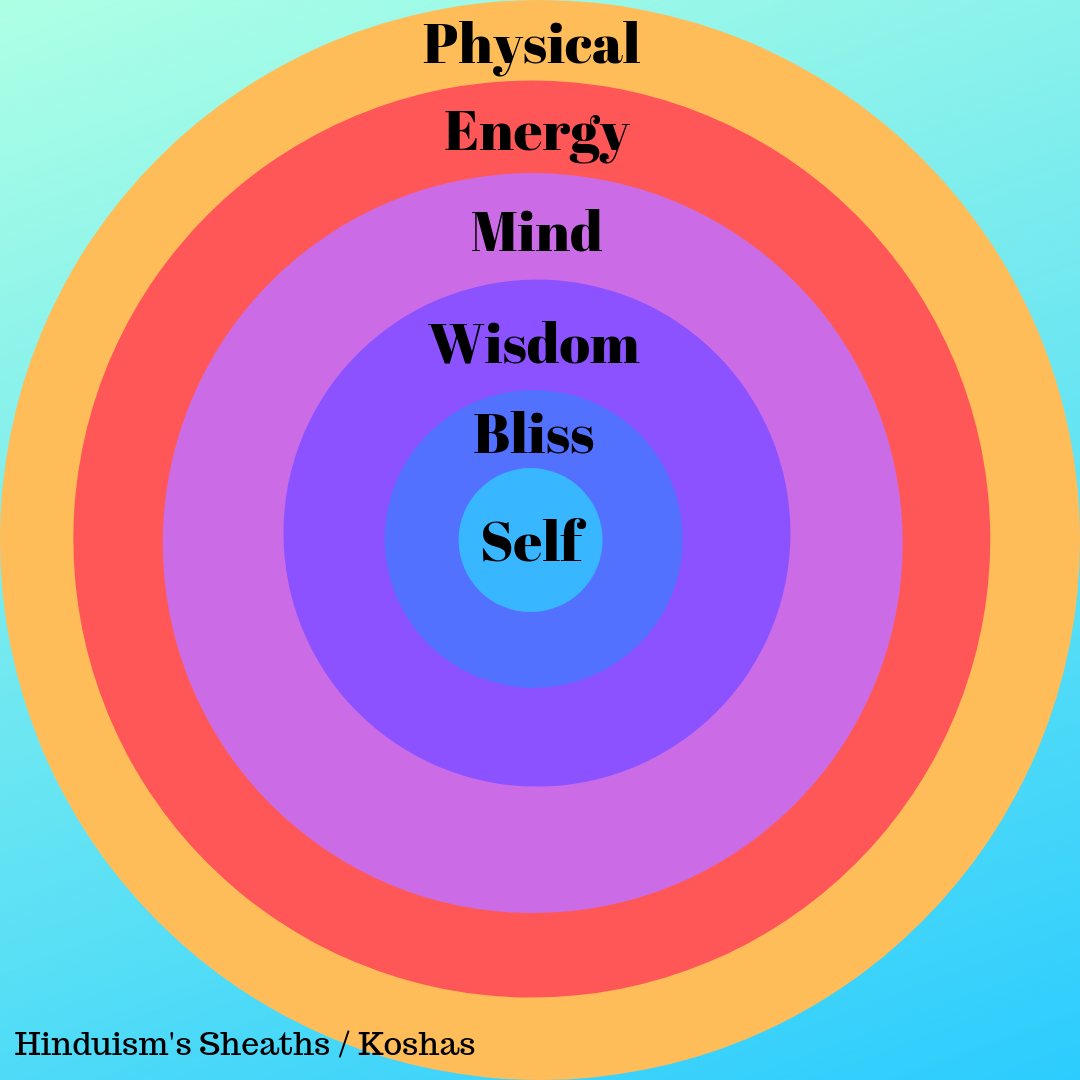

In Hindu philosophy, there is the concept of the five sheaths.

The oversimplification of the concept is that there are increasingly subtle aspects of ourselves working to form our experience all the time. This is an easy concept to wrap our heads around. We know it is easier to locate and understand our skin and bones than it is our thoughts, feelings, intuition, and spirituality.

What is not as easy to understand is why we have access to different levels at different times, and how some people begin to access the more subtle levels regularly, while others do not.

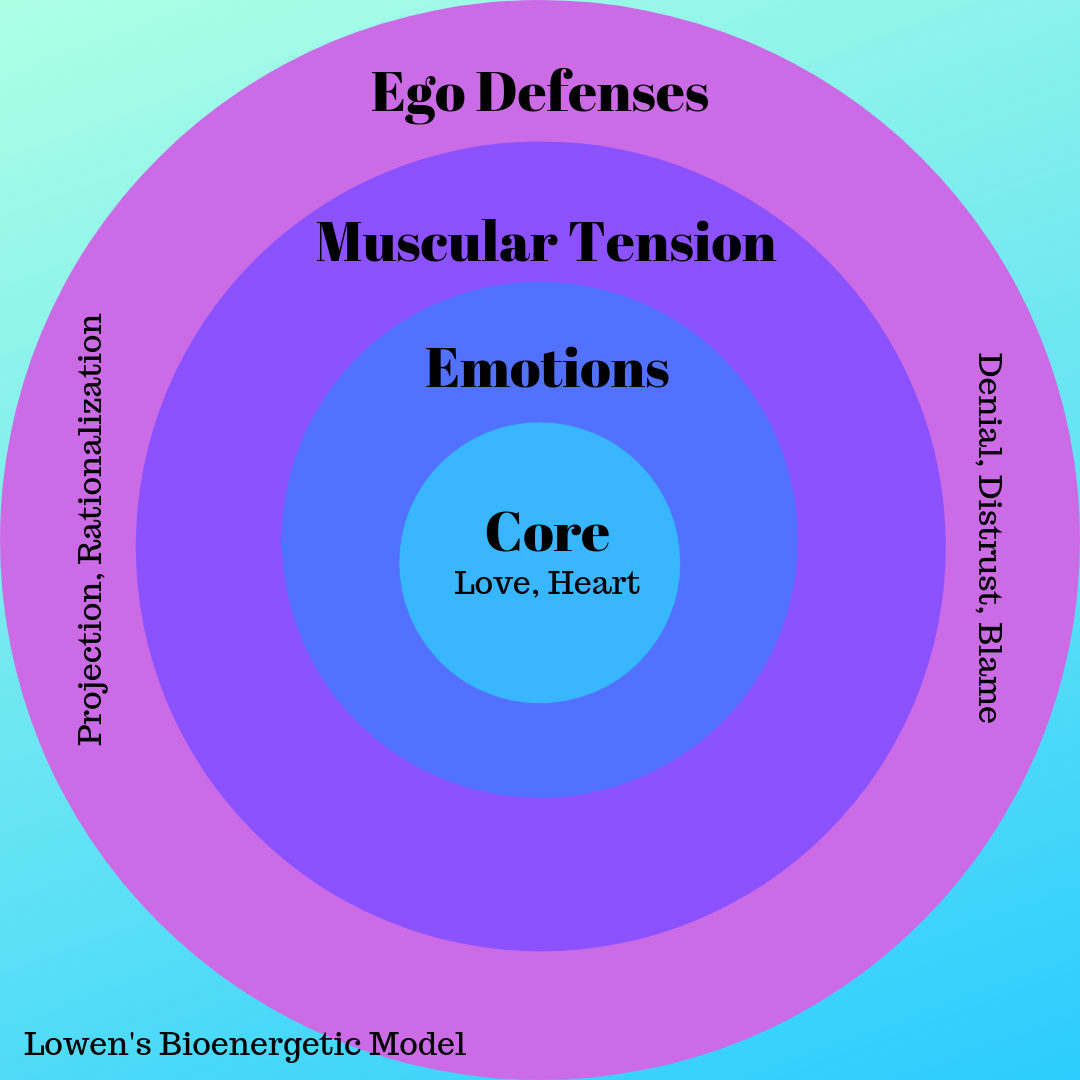

In somatic psychology, there was a man who drew a similar diagram to the one above. Alexander Lowen (a physician and analyst trained by Wilhelm Reich) posited different levels of experience one has to move through to reach their “core.”

His diagram (shown below) follows a similar premise as the five sheaths model, and suggests once again that it takes intense work and focus to access our personal subtleties.

Implicit Memory

In meditation, we spend long periods withdrawing awareness from thought and outside stimulation. Consequently, we begin to feel our body more. Over hundreds and thousands of hours, we begin to access these subtle layers. In so doing, three things can happen that many of us do not expect.

First, we may begin to access implicit memories.

All experience occurring before age three is stored in our body because our frontal cortex is not yet developed, and is therefore unable to process the memory in a healthy adult way. Such memories become imprinted in our muscles and nervous system. Essentially, if we had a perfectly safe holding environment during this time, our muscles remember safety and bear no signs of defensiveness. If not, our muscles and nervous system remember distressing events through chronic activation or numbing.

Also, as adults, we can go through experiences so traumatizing that our normal way of recalling everyday events—episodic memory—would lead to a constant sense of overwhelm, and we therefore stuff them into our body in a similar way.

This type of bodily memory is implicit, and is only a problem for those of us with traumatic memory stored in our tissues and nerves. Unfortunately, that is a lot of us. My spontaneous self-assaulting movements that arose, coupled with shame and fear, constituted a physical reenactment of a shameful infanthood experience I was regaining through implicit memory. Thus, meditation began to suck.

Autonomic Dysreglation

A second potential happening is that our nervous system begins to display wild dysregulation. This phenomenon is actually observed by Vajrayana Buddhists and they call it Retreat Lung (lung meaning wind) or Meditator’s Disease. When this happens, even the Buddhists think meditation is a drag.

Oversimplifying the concept of nervous system regulation drastically, I can say that our autonomic nervous system is meant to operate through oscillation and containment. When the inhibitory and excitatory aspects of our nervous system (the parasympathetic and sympathetic, respectively) are operating healthily, we move in and out of activation with little disruption.

However, when an experience overwhelms us, one side of this oscillating system breaks out of healthy containment, or both the inhibitory and excitatory aspects fire simultaneously, causing all sorts of problems.

When we begin to recall implicit memory and gain greater felt-awareness of our nervous system, we discover the profound dysregulation that is already there. It might seem as though we activated it through the process of meditation, but we did not. This dysregulation has been there since the traumatic experience that caused it, only we developed vastly complex ways to keep it suppressed and out of our awareness.

A similar concept is upheld by many spiritual traditions in regard to our own potential: our perfection already exists; we have simply buried it in obscurations.

The damage done to our physical and subtle bodies through this suppression is known as allostatic load. Our bodies are not meant to deal with constant stress and dysregulation and the toll on our health is serious and long-lasting.

The Freeze Response

Lastly, the act of sitting still on the meditation cushion for extended periods of time can activate what Dr. Peter Levine refers to as tonic immobility.

Tonic immobility, to oversimplify once again, is the freeze response we animals exhibit in near-death experiences. When we cannot ask for help, and when fight or flight are no longer useful, our body releases large amounts of endogenous opioids (to numb the arrival of pain) and our body goes limp into submission.

For those of us with trauma—either early or late in life—there is usually a bout of tonic immobility hidden deep in our nervous system from a time when our ability to protect ourselves was thwarted.

Sitting for many hours in a still posture sends afferent nerve impulses to the brain signaling the re-arrival of this tonic freeze state. Given the amount of fear present the last time we entered this state, you can imagine that this is another time meditation begins to resemble an experience less like the cover of a yoga magazine, and more like torture.

Essentially, meditation is an attempt to be present, to be right in this moment, and to gain access to the subtleties that reside here. Coincidentally, a teacher of mine once offered a definition of trauma as “an inability to be in the here and now.”

Get Up, Yo

So then, with such a sh*tty dilemma, what are we to do when we access trauma on the cushion?

Get up and stop meditating.

Use the vast resources that exist to renegotiate our trauma symptoms: somatic psychotherapy, neurofeedback, acupuncture, nature, secure relationships, craniosacral work, and so on.

Interestingly, by leaving a meditation practice that sucks, and starting trauma work that really sucks—for a while—we eventually begin to achieve the same results we were trying to cultivate through meditation: calming our minds, becoming present and available for others, and accessing our own sense of spirituality. Circle unbroken.

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 6 comments and reply