“I’m sober Sheri. I quit drinking for you! What more do you want from me?”

There are so many things wrong with that declaration and question I shouted at my wife on several sober occasions before I relapsed and returned to active alcoholism.

In my defense, my reaction wasn’t aggressive nor evil. I just didn’t understand the disease from which I suffered. Alcoholism is all about shame and secrecy. Since no one talked about it, how was I supposed to understand my own addiction to alcohol?

I didn’t understand why my wife, Sheri, was still mad at me. I gave up the other love of my life, my beer and whiskey, because I thought that’s what needed to happen to repair my marriage. Sheri had felt like the second most important thing in my life for years. Offering to stop cheating on her with my liquid lover wouldn’t do anything to fix the pain of the years of betrayal.

I was so naive. I expected abstinence to fix everything. I put a burden on sobriety’s shoulders that it couldn’t possibly carry. After decades of drinking, I stopped, and I expected all the pain to—poof—just go away.

Alcoholism doesn’t work that way. The resentments won’t let it. When my wife was still frustrated, untrusting, and sad in my early sobriety, it made me angry. I could only see that which was right in front of me. My sacrifice—the challenge I faced to stay sober—that was an effort worth supporting and celebrating. I didn’t understand that my wife wasn’t much in the mood for a congratulatory party. Sobriety meant only a chance that new pain wouldn’t be added to the pile. Sobriety did nothing to address the hell into which my disease had transformed her life. When a man stops cheating, it doesn’t erase the pain of the past indiscretions.

In a relationship, sobriety isn’t the end of anything. It is only the beginning of a long, arduous, rarely successful trudge to save the marriage. Sobriety doesn’t fix anything. It just shines a spotlight on the problems. It is up to us to roll up our sleeves and do the work of repentance and rebuilding.

Even as an active drinker, I was mostly good about apologizing to my wife the morning after a painful argument or biting comments made while drinking. I wasn’t so blind and arrogant that I couldn’t admit fault. But I didn’t understand how meaningless those apologies were. Part of the process of forgiveness requires a belief by the offended that the offender won’t perpetrate the same offense again in the future. As long as I kept drinking, my wife knew I would get drunk and do it all again. As long as she knew my apologies carried with them my promise to be cruel and insensitive again in the future, they were completely meaningless—wasted words coming from a damaged brain, directed at a broken heart.

When I would take sobriety out for a test drive, I remembered the many occasions from the past when I had done wrong and apologized. I didn’t see the damage that remained because I was confident in my amends made in those many mornings after. Yes, I had been an asshole, but I had said I was sorry.

Sobriety, for me, was about moving forward. There was nothing left to address in the past. But since my alcoholic apologies came with a guarantee for more pain in the future, Sheri had deflected them, pushed the pain deep down inside and tried to move on. It was her only choice. Assigning the hope of possible change to my apologies could only end in additional pain. Hope and vulnerability are not options for the spouse of an active alcoholic. Self-preservation does not afford the luxury of trust.

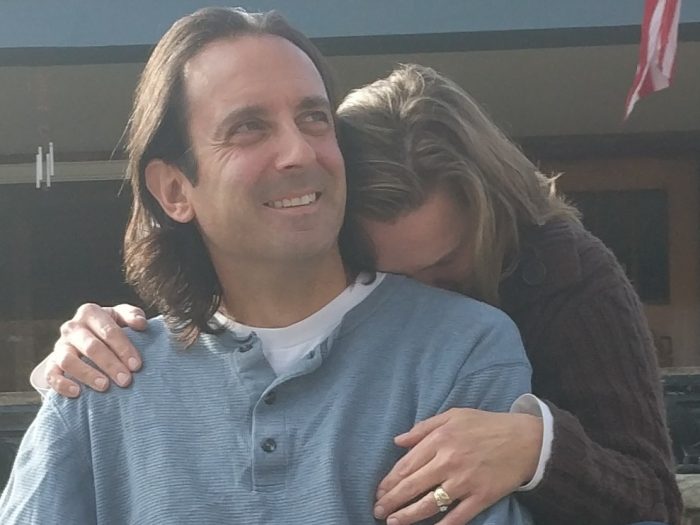

So there we were: a resentful woman and her newly sober husband. I was focused forward trying to muster the strength to defeat the beast that had brought me to my knees, and my wife was stuck looking back at the pain I’d caused her. I needed her to love me and trust me to help me find permanent sobriety, and she couldn’t begin to trust the man who had so often before let her down and crushed her soul.

Sometimes you have to move backward before you can ever hope to go forward. In a marriage in early sobriety from alcoholism, the first step to our recovery was to look back over our shoulders and deal with the aftermath of my two-and-a-half decades of drinking.

“I want a sincere apology for the devastating pain you have caused me. I want to believe somehow that it won’t happen again. I want to know the unknowable.” Those are the answers I wish my wife had given when I asked her what more she wanted from me when I quit drinking. I wish she had told me that. But she didn’t share that answer because she didn’t understand it, either. She was hurt. She was angry. To Sheri, my commitment to sobriety was like promising not to pour gasoline on the charred remains of our house after it had already burned to the ground. It was too little, too late. Sometimes you don’t get to rebound from disaster. Sometimes it just hurts too much.

I had to recover from addiction, and my wife had to recover from so many years spent in codependency and dysfunction. We both had an uphill battle, but on top of all of that—on top of what we thought were the greatest challenges of our lives—we had to try to recover our marriage. And we didn’t have a clue how to begin to do that.

So we didn’t. We argued in sobriety just like we argued when I drank. We retreated to the place we knew so well at the first sign of irritability or frustration. We argued over inconsequential things like eye rolls or dismissive looks. Our skin was worn so thin from years rubbing each other the wrong way that the slightest abrasiveness was enough to send us reeling. All questions seemed to be loaded, and even compliments seemed to carry an air of disapproval. How do you love someone you don’t like to be around? That question without an answer was paralyzing for a long time.

Everyone knows that alcoholism destroys marriages. I’ve read about a 20 percent increase in divorce rate when abusive drinking is in play. But I’ve never been able to find statistics about the divorce rate of marriages when the abusive drinker is in recovery. I don’t think that is a subset that’s ever been studied scientifically. But I’ve studied it. While my sample size is not large enough to publish the results, something like four of every five marriages I’m aware of where an alcoholic spouse quit drinking resulted in divorce. That’s an unscientific 80 percent, and I think it’s probably a little on the low side.

We had survived alcoholism and faced the extreme likelihood of our marriage dissolving in sobriety. Isn’t that just a kick in the ass. We were trying to get better, and everything was getting worse. Alcoholism carries with it relentless punishments. The destruction lingers long after we drink our last drop.

We didn’t know what to do. We read all the articles and talked to therapists and thought all the thoughts in an effort to make things better. None of that much helped. Like an optical illusion that you can’t see until you hold the picture at just the right angle, we had to let go to learn to hold on.

The answer was in the arguments. When we fought in sobriety, eventually, the resentments of our alcoholic past would bubble up to the surface and Sheri would be relitigating a dispute from years ago. I thought she had an unnaturally good memory. I thought she was stubborn and broken, and she was to blame for her inability to move forward. I thought we were doomed. We both did.

But then I listened.

I heard the pain of years old transgressions oozing from my wife as though the wounds were wide open. I had apologized. I thought injuries from the past had healed. My wife, on the other hand, was incapable of forgiveness because my apologies were so meaningless. The resentments remained. They festered and metastasized and wreaked havoc on our marriage. The past had come back for vengeance on the present, and the only way forward for my relationship was to fully resurrect the pain and tell my wife how sorry I was all over again.

This time had one fundamental difference. I had put down some serious time in permanent sobriety. This time, my apologies weren’t reminders of my inability to control my drinking. They weren’t promises that I’d make the same mistakes again. This time was different. This time, Sheri found the grace to forgive me.

We had to move back before we could dream of moving forward. We had to revive the terror before we could see a hopeful future. I had to apologize again—with the promise of permanent sobriety this time—before Sheri could figure out how to forgive. The survival of our marriage lived in that forgiveness. The seeds of trust sprouted in that forgiveness. Our marriage was reborn through the power of resentments forgiven.

The work required for me to recover from alcoholism was monumental, but it paled in comparison to the work we’ve done to recover our marriage. The odds are against us, and the journey is treacherous. But we’re making progress. We’ve backed up enough to be moving forward again.

Sobriety is not enough. Sobriety is never enough. But if you want it badly enough to listen, you can hear the solution crying out from the pain.

~

If you’d like to know more of the story of our alcoholic marriage and our progress in relationship recovery, please download our new e-book, He’s Sober. Now What? A Spouse’s Guide to Alcoholism Recovery for free.

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 41 comments and reply