“The only certainty is that nothing is certain.” ~ Fortune Cookie

~

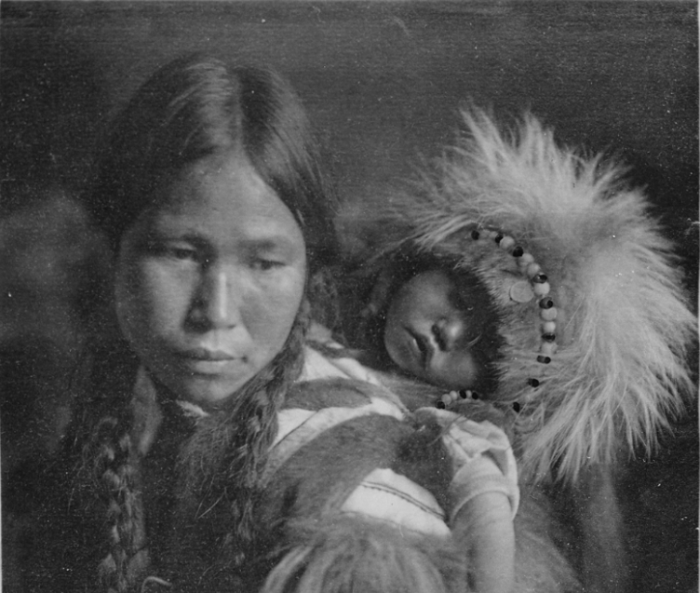

Reflections on Native American Heritage Month as a Non-Native to this Country

I sit at a Taoist meditation gathering, legs crossed, balanced on a plastic folding chair.

My Qigong teacher has just given a lecture on the Tao, and I expect now to sit in silent meditation and take in the familiar sound that always ends these nightly talks: the music of the gong.

“The gong” is what my teacher calls it, anyway. What I call it is a crystal singing bowl. The diameter of a beach ball, it’s a half-cut oval of frosted white glass that rings when struck and sings when stroked. When a musician sits down to play the bowl, gliding a wooden dowel around its outer edge in unbroken spiral after spiral, the crystal begins to sing. It starts quiet and scratchy, and builds to a crescendo of expansive song so loud and wide that it penetrates the air of the room and and cancels all other information inside.

The loudness of the gong silences everything in its wake.

The music of the gong is one of my favorite sounds. It’s a mystical sound, a sound seemingly from another world that somehow crosses into this material world and touches spirit to ground. Its ring expands through space like dust of a galaxy, enters my ears, and rings into my brain, echoing and bounding inside my skull. Every time I hear it, the song cuts through my consciousness so completely that it clears away everything in its path: any residue of thought, any dust of impure emotion.

I’m left afterward contemplating pure sound, hearing it recede, feeling my own self floating halfway between worlds. I myself feel momentarily both in this world and in the world of the unseen, the gong having transformed even my own energy into sound. I am left clear, renewed, with a sense of seeing and hearing again for the first time.

The clarity lasts for a few minutes, maybe a few hours. Then, inevitably, whatever is inside my psyche and experience will begin dropping its litter into the pristine fields of pure mind, and my neural highways start to become congested again. Life traffic builds up and starts honking.

I once told my teacher, “I love the sound of the gong. It opens me up like the sky.” He replied with a nod, “The gong is a great teacher.”

Tonight, back on my plastic chair, I once again await the gong. But tonight it doesn’t come. Instead, the voice of my teacher reaches into the dim light of the room, announcing that instead of meditation, tonight we’ll be gifted a unique presentation from some special visitors.

In the fall, we celebrate Native American Heritage Month in our country. As I ponder the meaning of that celebration, I think of a comment I heard recently from philosopher Noam Chomsky, remarking on a review of a book by someone he calls a “major American historian.” He said, the book’s author mentions that when early European explorers came to the Western Hemisphere there had been approximately one million native people living up and down the length of the continent. But the historian was far off in estimates of the true population, which Chomsky says would have been closer to 60-70 million.

Why the discrepancy? How did a historian miss 59 million-or-more people and instead only report one million?

Answer: by failing to count the millions upon millions of indigenous people of those lands who were killed—by disease, famine, and war—in the wake of the European settlers’ arrival. Why were those people either not counted, or dis-counted? Did the European settlers (or historians) of that time not see those many millions of people? Did they see them, but not see them as people? Did they see them as people, but following some narrow-eyed convention of the day, presume the native people of the Americas literally did not count? Or, did they see it all and just decide to cook the numbers to hide any blood that might be on their hands?

Back at the Taoist center, the special visitors arrive.

The troupe from the Centre for Indigenous Arts enters into the space. They slide in like shadows, silent, barefoot, carrying feathers and drums and strings of twinkling lights. Surrounded by statues of Kuan Yin and Taoist warriors, red and gold brocade yin-yang adorned tapestries, the indigenous dancers sit in a circle on the floor with branches of pine and juniper at their feet. They begin to chant.

The Taoist seekers of ancient times aligned themselves with the natural world. Taoist mystics climbed mountains to heaven, divined their destinies in numbers and geometries, shape-shifted into animals, contorting their bodies into deer, tiger, crane, and monkey. The energy lives on in this room, now. The indigenous visitors breathe their own offering to the space. The drum sounds, evoking bear, buffalo, eagle, and wolf.

A voice speaks from the darkest corner. A woman’s voice—strong, settled, confident. She gives a prayer in an indigenous language, a tongue my ears don’t understand. She shifts to English for a moment, calling on the ancestors for protection, honoring them, and thanking them for all life. She prays for the waters, the sky, the rocks. She prays for the people, to be at peace with one another and with all our relations, to live in joyful communion with nature and spirit.

Just as I wonder whether this woman might be asking too much of human beings, she utters something clear and wonderful that catches my attention:

“We are all indigenous.”

She repeats it again, and again. We are all indigenous. We are all indigenous. We are all indigenous to this Earth.

“I am indigenous to this land. And so are you,” she says. “I am indigenous to these waters, and so are you. I am indigenous to this soil, and a child of Mother Earth, and so are you. All of us—all of us—are indigenous to this world. We belong to it. It is our home.”

She continues, “If we are to find peace with one another, we must understand that this planet is our mother, and we are all brothers and sisters. We were all born from the same womb. There is no such thing as my land and yours, unless we say it is so. And if we don’t care for the land as our mother, if we don’t care for our shared home together, we are in danger of destroying her. Please, join with me.”

The room falls quiet. The only light comes from strands of twinkling bulbs strewn across the floor, and their reflections in the many mirrors that circle the room. Blue and white sparkles surround us all like stars. For a moment, a shared understanding fills the room that we are all one, of the same mother, praying under the same sky. And then the dancing begins.

I understand there’s a danger in making the statement, “We are all indigenous.”

It would be naive at best, and inflammatory and disrespectful at worst, to make this claim thoughtlessly. The land we call the United States was native land for hundreds of generations before any “modern” European set foot on its shores. And I admit, only because it was a native woman who spoke those words—“We are all indigenous”—did I feel some sense of permission to repeat it, as though it was anything I should possibly be allowed to say.

As a woman of European ancestry, why do I feel I need permission to say such a thing? Where does that come from?

I have an herbalist friend who is Irish by blood. Sharing the ancient ways of the Irish warrior goddess is her life’s work. She teaches herbal classes rooted in Irish traditions, healing, and spirituality. She leads a mystery school of indigenous wisdom in the tradition of ancient European mystery schools.

This friend, who lives in the United States, far from her ancestral home, wrote once that she sometimes feels like a woman without a land. She knows she doesn’t “come from here,” yet here is where she is. And she must dig some roots where she is, yet knowing that someone else long ago dug here first, and still holds the ground sacred.

So this wild-skirted woman plants one foot in this land, and the other in the rhythms and seasons of her lost home. From here she teaches the trees of the Celtic year: Hawthorne, Ash, Birch, Willow. She shares recipes passed down through the generations of mothers and daughters before her. She weaves her stories, not beside the warmth of a peat fire on the rocks of the Irish Burren, but through the smoke of burning mugwort in the arid mountain west. Wherever she is, she must tell her stories.

I can relate to this. As a woman with a bloodline threading back to the British Isles, just the names of the Celtic trees tug softly on something inside me, calling me out to sea. They speak longingly, “You know us. We are yours. You are ours.” Yet, I was born here. Where do I belong? What does it mean to be indigenous to a place when inside me flows the black blood of forested island lochs, while I was birthed through my mother, from my mother’s mother, on the sagebrush lava flows of the high desert? In both places I feel equally at home.

It would be untrue to say that we are all indigenous to this land. Each of us has roots in some land. We can call ourselves indigenous to somewhere. If this land is not the land of our recent ancestors, we can find beauty in that recognition, and take care to honor the indigenous heritage of the place we are.

And if our roots were uprooted from somewhere else, somewhere far away, we can grieve for that loss of place. Maybe we can have compassion for others who suffer the same loss.

Recognizing that we are all indigenous to this earth, sisters and brothers to each other and all of creation, is not meant to ignore the pain of genocide, the devastation of colonization, or the loss of self and identity that comes with separation. We live in a world of borders and nations, a world that has split people from their native lands in many places, many ways. This is our reality. We can’t go back and undo the damage that was done, not fully, despite reparations and best intentions.

So I wonder, couldn’t the words “we are all indigenous” be words of healing? If we are all indigenous to this planet, and all in need of a home, could that understanding be a source of empathy, a path of reconnection for those who have lost connection to their lands, all around the world?

I would be interested to know what others think of this idea. Because to me, it brings peace, hope, possibility. What would the world be like if we could all know that we are already home?

Back to the sound of the gong. I am not Chinese. I am not indigenous to any Taoist tradition. Yet the gong sings to me, empties me, fills me with wonder. I can only assume the gong does not discriminate, that it offers its song of clarity to all of us equally, wherever we may be from.

My intellect is not certain of any of this, because my intellect is afraid of being seen as a colonizer who does not have a right to say such things as “we are all indigenous.” I’m not certain about my land, about my permissions. I’m not certain what my place is, my place to live, my place to speak.

But my heart is not afraid, and I trust my heart.

I am certain that I am indigenous to this planet, and I am certain that you are too. I pray for the day none of us feels like a woman without a land, a man without a land, a child without a mother. We should never need to feel that way, not when we are all already home. I pray that is something we can work on together.

So, no gong tonight, but still some clarity. Another good teacher, and teaching that will echo through my consciousness, in a different way, for more than a few hours.

A tall and strong native woman emerges from the darkness of the corner, and enters into the circle of light. It is her voice I heard in prayer. Silver hair flows over her shoulders and cascades down to her hips. Her skirt is laced with leather and fiber. Feathers adorn her hair. She dances a spiral, hands high in the air.

Dear wise woman teacher, thank you for speaking your prayer. Thank you for giving me permission to stand tall in this land with you. Thank you for sharing your strength with me so I can confidently say, “I am indigenous to this world. We are all indigenous.”

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 16 comments and reply