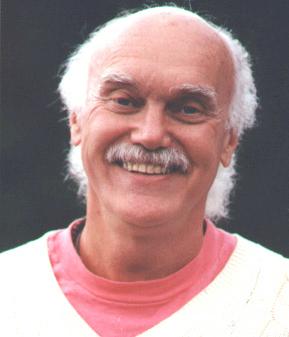

Ram Dass, the beloved pathfinder, wayshower, and teacher, died on December 22, at 88. As most readers know, in the early 1960s, when he was Harvard psychology professor Richard Alpert, he and Timothy Leary were the Sundance Kid and Butch Cassidy of psychedelic advocates, provocateurs, and outlaws. Then, in 1967, he went to India. What follows are excerpts from the section on Ram Dass in my book, American Veda.

One day in Katmandu, Alpert, then thirty-five, met a long-haired beanpole from Laguna Beach, California, named Bhagavan Das. . . . Bhagavan Das took his new friend to meet his guru. The highlights of Alpert’s encounter with Neem Karoli Baba are now part of spiritual lore: the aging sadhu who owned nothing blew the mind of the spoiled Ivy Leaguer by knowing things about him he couldn’t possibly have known; the scientist fed the guileless guru a huge dose of LSD and watched incredulously as nothing happened; the ice of scientific skepticism melted in the white heat of unconditional love. Instead of leaving India two days later, as scheduled, he stayed five more months, soaking up his guru’s darshan and learning about Vedanta and Yoga.

He returned to the States in 1968, bearded, beaded, berobed, and redubbed Baba Ram Dass. Ram Dass means “servant of God,” and he served God and guru as a kind of Pied Piper, turning on the turned-on generation to an ancient path of liberation, spinning tales, cracking jokes, and expounding Vedanta-Yoga (with generous servings of other wisdom traditions) at satsangs and retreats. Many of the young seekers treated him as a guru, and like most mortals, he probably enjoyed it. But by all indications, the adulation wore thin after a while. “A teacher points the way, and a guru is the way,” he once said, “so I guess I’m not a guru. I’m a teacher.” It was probably for that reason that he dropped the paternal Baba from his name.

A Ram Dass road show materialized, complete with tour manager and kirtan band. Part Himalayas, part Harvard Yard, part vaudeville, it was a huge hit, and not just with the hippies. “It was as if the whole culture was waiting to be turned on by the East,” Ram Dass said. His academic credentials made him a perfect crossover figure, especially among psychologists. Despite all the hoopla, or maybe because of it, he made regular visits to his guru for “heart-to-heart resuscitation.”

In 1971 Ram Dass published the iconic Be Here Now. It contained an autobiographical overview, a how-to “cookbook” with a variety of yogic practices, cogent quotes from the wisdom traditions, advice for living more consciously in the world, a fourteen-page list of recommended books, and the famous brown pages. Read by turning the book sideways, it’s the print equivalent of an extended jazz solo, with the lyrics, so to speak, juiced up with decorative fonts and lines that circle and curl, and a rhythm section of pen-and-ink drawings.

. . . .

He made sure everyone knew that he, like them, struggled with how to integrate spirituality and “real life.” He wrestled with his ego, his relationships, his sexuality, and all the rest of it—all grist for the mill, he said, and made that the title of his next important book. He was not a bhagawan or a maha anything or a such-and-such-ananda. He was just a guy who knew more than most and could explain it exceptionally well—and get laughs in the bargain, making everyone feel like they were in some cosmic sitcom together. That mix of expertise and self-honesty made him not just respected but beloved among seekers who wanted to identify with someone more like themselves than an exalted guru.

. . . .

Ram Dass had promised his guru not to tell anyone who or where he was, but he couldn’t help himself. From the time he returned to India in 1970 until Neem Karoli Baba’s death three years later, a few hundred Westerners found him. They went to India for reasons ranging from a passionate search for the divine to hippie narcissism, but a remarkable number have made a mark on American culture, inspired by the old man whose motto was “Love, serve, remember.” His emphasis on service produced living counterarguments to the criticism—not entirely erroneous in the 1970s— that Indian teachings led to social detachment. [Among the youngsters who tagged along with Ram Dass in those days were many who became influential figures in contemporary spirituality, e.g., Krishna Das, Jai Uttal, Jack Kornfield, Sharon Salzberg, Lama Surya Das, Daniel Goleman, Larry Brilliant, and Mirabai Bush.]

. . . .

By shifting into responsible service with the Seva Foundation, an international public health organization, and the Hanuman Foundation, which served prisoners and the dying, Ram Dass was once again modeling the course that others would follow as they matured. Quite likely, he did it again when he suffered a stroke in 1997. That too was grist for the mill. “For me to see the stroke as grace required a perceptual shift,” he wrote. “I ended up looking at the world from the Soul level in my ordinary, everyday state. And that’s grace.” . . . .

When I interviewed Ram Dass in 2007, by phone from his home in Maui, his stroke-impaired speech was much improved since the time I had heard him lecture a few years earlier, but he still had to pause at times to wait for the words to crawl into his awareness “from the lobby.” I asked him to assess the role he played in conveying Vedic teachings to the Sixties generation. There was a long pause, either because of the stroke or because he wanted to find the right image. “I was an uncle,” he finally said. Uncle was the right word. He was a trusted elder and a believable guide, like your parents’ cool kid brother—older, but not too much older, with Ivy League authority and the cachet of having left the establishment. Before he hung up the phone, he deferred to his guru. “I was just playing with Maharaji’s energies,” he said. “I was Charlie McCarthy”—the puppet of ventriloquist Edgar Bergen.

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply