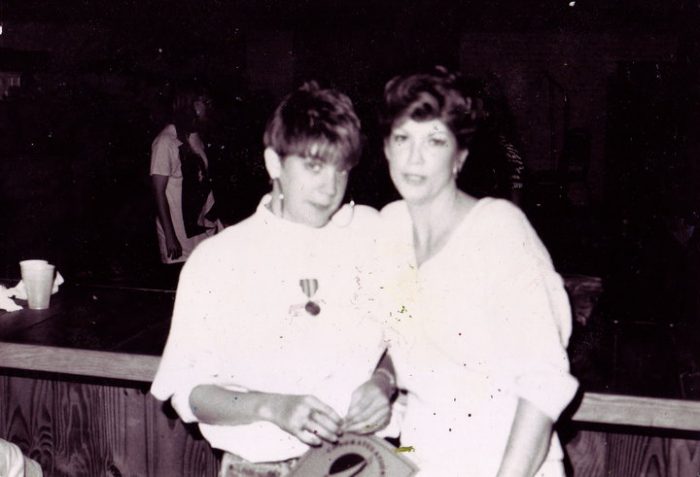

I thought that I knew the woman who was my mother quite well.

She had gone through so much in her own life with grace and strength. She had put up with so much from myself and my younger brother. She was encouraging and supportive of all of my obvious developing eccentricities.

She did not blink when I first shaved my head at age 14. She looked the other way as I took apart and reassembled my bedroom furniture the way I wanted it to look, and ended up finally with just my mattress on the floor. She did not balk at the huge bedroom wall mural in acrylic and spray paint, replicating all of my favorite album covers. I thought of her as the one person who only wanted me to be happy. Even when I attempted suicide, ran away from home, and eventually moved to another town altogether, all by age 16.

In 1997, she was involved in a bad car accident. It was a front-end collision that completely totaled her car. When the driver’s side airbag “exploded,” it released a powdery dust into the air that she inhaled deeply in her surprise. This dust not only would eventually be the cause of severe pneumonia going forward, but the airbag itself did not prevent the steering wheel from breaking a rib which then punctured her liver straight away. This caused some internal bleeding, and later, serious scarring.

Okay, I’m not a medical expert, but I will do my best to explain what happened next in the way that it was explained to me—or at the very least, the way that I understood it.

The scar tissue that formed in her liver became cancerous. I was told that she had cancer cells present in her bloodstream, looking for a place to attach and to grow. The scar tissue in her liver was the perfect small pocket for these cancer cells to attach, and grow they did. Diagnosed in October 1998, by February 1999 she was dead.

In August of 1998 she told me that she was sick. Her doctor had taken a biopsy of her liver. They found cancer cells there. She would soon begin radiation therapy. But I should not worry, because she felt fine. She would continue to work, and I should go on about my life as usual. She promised to keep me up-to-date on any new developments. By October, she was told that she was going to die. That the radiation along with chemotherapy would only make her last weeks miserable, and that the cancer had spread. She began to get her affairs in order.

I completely rejected this information upon hearing it. I absolutely refused to believe this was happening. I decided that my mother was nuts. Overreacting. A hypochondriac. Her voice sounded like her regular self on the phone. She was being dramatic. She was only 55! She had a head of bright red hair. Not a single grey strand to be found. She was going to live to a ripe old age. I was going to repay her for all that she had put up with. I was going to take care of her.

I finally flew home to visit her for Thanksgiving. We went shopping. She sweated a lot. She was high-spirited and had decided that she ought to just go ahead and max out her credit cards because she would not be around to pay off the balance. She found it endlessly amusing to tell the salesperson at the department store, the kid at the drive-thru window, our waiter, anyone whom she encountered throughout the day, that she was “dying, dammit, hurry up, please, I do not have all day.” She bought me a ring and called it an “heirloom.” On Thanksgiving day she did not get out of bed. I burnt the pecan pie. I took pictures of it. She wasn’t hungry. I flew back home that weekend. She didn’t feel well and did not come with us to the airport.

I should have gone home to visit her at Christmas that year but I didn’t. She still sounded well to me on the phone and somehow I was able to convince myself that she was. When I had left her a month earlier, she had weighed at least 140 pounds. I have a video that my step-father made of her opening presents on Christmas morning—if only I had known that she had become so gaunt, that she struggled to understand what was going on around her, that she was so weak. For her birthday on January 6th I sent flowers. I have photos of her smelling them, a walking skeleton holding a bouquet shaped like a birthday cake. By that time she was down to about 98 pounds and struggled to stand. No one in my family told me this. I saw the photos later. But if I had stopped to think about it for just one minute, I would have known. But I didn’t.

I finally flew back home again the first week of February. And as I arrived, I caught her last hours of consciousness. I went to her bedroom, where she laid on a rented hospital bed with bars on the sides. She was hooked up to a respirator. There was almost nothing left of her. The way that her teeth looked in her skull, her eyes had sunk so far back into their sockets that they were almost not there, her ears seemed to hang loosely backward as if the only thing holding them onto her head was the bright red hair that she still had, flowing beautifully over her pillow like pureed carrots. She looked at me and I tried to hug her, but it hurt her to be touched. I told her I loved her. She fell asleep, and within an hour, she was in a coma. She would stay in this coma state, mostly, until the day that she died two weeks later.

When someone is this ill, and in this much pain, the goal of those around them is obviously to make them as comfortable as possible. My Mother’s coma was not like the ones I had seen on television or in the movies. She moved a bit, squirmed around subtly in her extreme discomfort. She whined quietly or winced when touched, she sucked on small sponges of water on sticks that we touched to her lips, never opening her eyes. Morphine patches were eventually doubled, one on each shoulder blade, one on her chest. She slept in diapers, we changed them, cleaning her with a warm washcloth.

We, myself and the many extended family members who stayed in her home those final weeks, were instructed what to watch and listen for. A “wheeze” a deep whine in the lungs is a “death-rattle”—the sign that the end is near. And when it finally arrived the witness was to write down the time of death for her records. And so we set about waiting. We waited in shifts, taking turns sitting vigil beside my mother, around the clock.

My shifts were from 4 a.m. to 8 a.m. and some days 4 p.m. to 8 p.m. The early mornings sitting there next to my mother’s bed, listening to her breathing, trying to make her comfortable, offering her water, talking to her—or what seemed to be left of her—a body, a nothing. That last two weeks was like some sort of sensory deprivation tank. That room, her breathing, the soft music playing, the hum of the respirator, the dark.

One early morning she began to make a moaning sound, as though she might be irritated by something unknown, so I thought that perhaps she wanted some water. I pulled the stick with the small pink sponge on the end of it out of a glass of water on her bedside table, held it toward her mouth. Suddenly, and with amazing strength out of nowhere, she sat straight up like a shot and with her toothy skull, bit down as hard as she could onto my hand, pink sponge and all. She held her thumb and forefinger in her mouth, and in that split-second bit down as hard as she could. I was in shock, and yelled “mom!” She startled, and looking right at me as if to say “what?” she suddenly had complete clarity in her open eyes. And then, just as suddenly, she laid back down on her pillow, and was gone again. I burst into tears.

Morning after morning, coffee after coffee, talking to her and at her, crying, yelling, begging her to finally go. The hospice nurse kept coming to the house to check on her. She would often say something like, “I think she may just have 24 hours left” and then wouldn’t you know it, two more days would pass. The cancer that had taken over her liver was huge now, grown to an enormous size compared to the rest of her body. Taking all of her energy, draining her life force. My mother was starving to death, and we were supposed to make her comfortable while her cancerous liver essentially ate her alive. For what seemed like forever we held her hands, stroked her hair, wiped her bottom. We talked about what it might be that she was waiting for, what she knew or didn’t know. Was there someone not here who she was waiting to arrive? Some unfinished business?

The day that she died it happened at 2:00 in the afternoon. The time was logged. At her time of death, I was ironically outside, smoking a cigarette. My younger brother’s girlfriend was with her when she passed. My cousin came out to tell me. We undressed her, and bathed her. We washed her body in her own soapy scent and dressed her in her favorite cotton nightgown. I did her hair for her, pulling it up onto the top of her head in a neat bun. It occurred to me that the bobby pins that I had used were going to burn and melt into her beautiful hair when she was cremated. My brother went to his bed and crawled under the covers, his knees pulled up to his chest. And then they came to get her. We all followed the guys from the funeral home out to their van, my mother on a gurney under a white sheet. A small gathering of family and friends silently watching as the van drove away.

I stayed one more week after that as a memorial service was planned. I received a small container of my mother’s ashes. I flew home, holding it in my lap.

I never said goodbye, or got a goodbye from her. I felt sorry for myself about that for a long while afterward. I never got the chance to say how sorry I was for so very many things. I was angry with her for taking so long to go, for putting so many through so much. I was angry at her for not leaving a note behind for me, telling me that she was proud of me, that she loved me. I was angry at her for biting me. Angry that that was her last communication with me. I need her. I need to be able to call her on the phone. To tell her what I am up to. I miss her. I miss who she really was, and I miss the woman who I thought that I knew.

~

Read 3 comments and reply