Always, I carry the weight of not writing.

Moments seem to perpetually be not what they could be because of a niggling in the back of my mind, sometimes in my chest, often in my stomach. A pang that’s subtle enough that I can be distracted from noticing it, but present enough that if I look for it at any given time, it’s always there.

It’s the knowledge that no matter what I am doing, if I haven’t written that day, then I should be writing.

No matter how beautiful the sunset, how engaging the conversation, how hilarious the movie, something is always just sorta kinda off.

But, let’s be honest, writing is the worst. It’s hard, embarrassing, and awkward. I don’t want to have to do something every day that isn’t going to reward me in some way.

And there it is, that’s the crux of it: doing something for nothing.

If it’s not going to bring me money or accolades, then what is the point? I’ve asked that question, I’ve avoided writing for weeks, I’ve been obstinate and refused to budge. But here’s the thing, when I do it—when I show up to the page—that nagging feeling that shadows every single day goes away for one.

The difference between how I’ve shown up for my yoga practice and my writing practice is likely why writing seems so much harder than yoga: because I thought I had to be good at writing. I thought I had to produce something of value, something worthwhile, something great. I’ve never felt such pressure with yoga—if I get myself to the mat, I consider it a win regardless of how the following 90 minutes are spent. With writing, I thought I had to make something happen, make magic, so of course that kind of pressure would make anyone want to run and hide.

I was right to avoid it if the only way it could have any value was if I wrote something great. But if I take greatness out of it and assume most of it has nothing to do with me at all, then it gets a whole lot easier. The only part I need to concern myself with, then, is the showing up part.

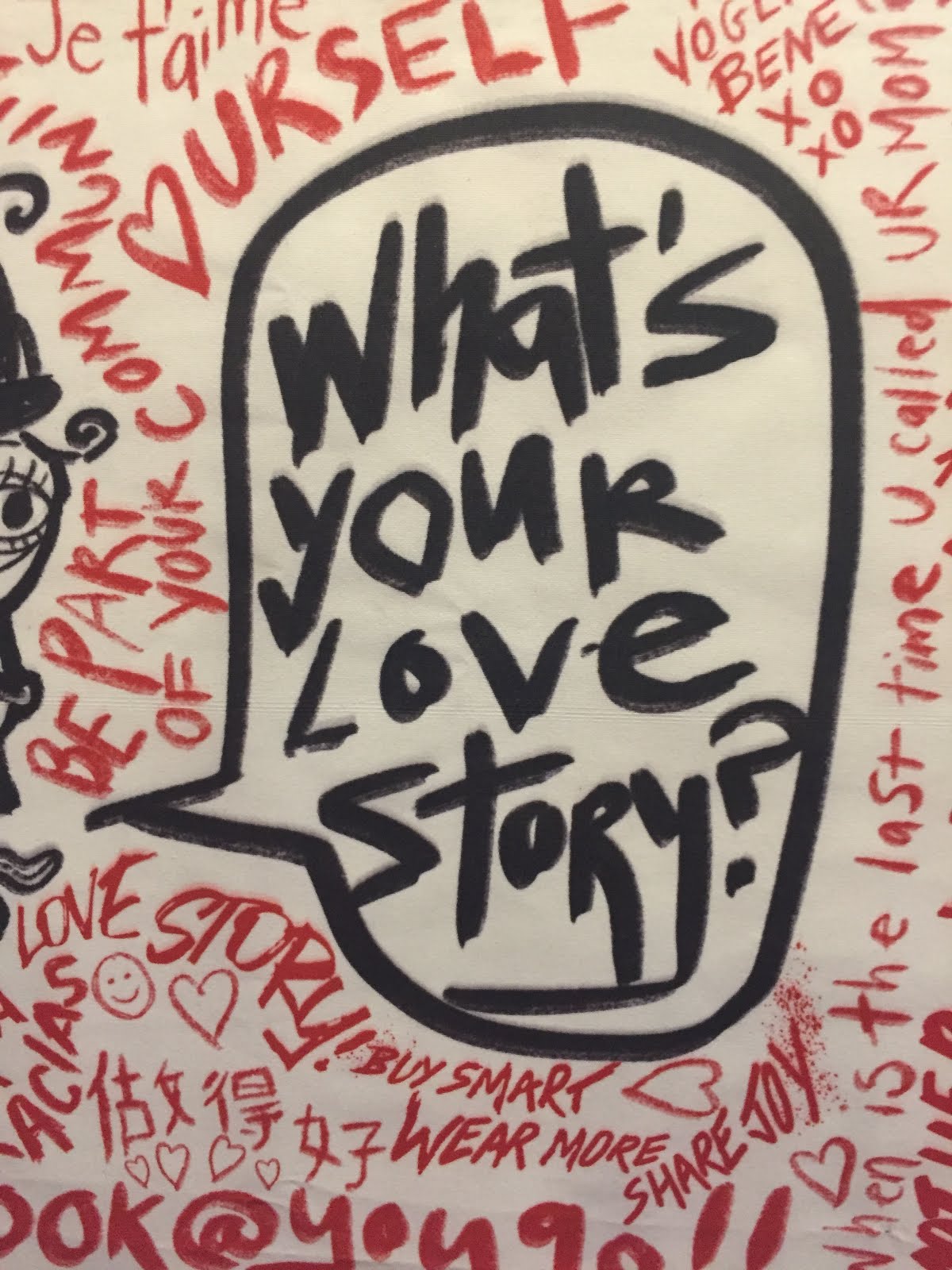

Create (bad) art if your soul is asking you to. You’ll know it’s asking for it if it feels like a low-grade fever, a low-level irritation where something is always just a little off no matter the situation. Nothing is identifiably wrong, but something just feels off. It’s like a mosquito in the room—not all that close to you, but present and getting closer, and you know it’s going to be hard to sleep because of it.

I was at an amateur comedy show the other night. I’m not a huge fan of stand-up comedy, but sometimes the energy of being in the room is fun and the humans on stage get it right. Some of it was good, and the MC was pretty funny.

And then one guy got up and he sucked. I was pissed.

“Who do you think you are? Getting up there, not being good, and wasting my time?”

My anger surprised me. It was, of course, a projection. I’m a performer and often my fears and insecurities about being bad or wasting the audience’s time are what keep me from doing it more regularly. I resented his ability to go up and do what I’m too afraid to do—show up and be imperfect. Once the wave of anger passed, I felt pity for him, “Oh you poor thing. You never should have gotten on stage, I’m embarrassed for you. I’d like to protect you from this.”

He did not need my protection. It was I who needed him.

I believe that art needs an audience. Pieces often aren’t complete until released into the world to be viewed by the masses’ eyes, but the value artists give society is greater than the gift an audience gives to artists. By getting up there, whether he sucked or not, he was contributing to the conversation. I, as an audience member, was participating, perhaps, but only by reacting. I was not propelling us forward by being there; I was merely responding to someone else’s efforts to do so.

All an audience can offer is (potentially) steering the course, but it is the artist who propels us by their own creativity, bravery, and force of will. No courage is required to sit in an audience; sh*t-tonnes of courage are required to step onto a stage, and even more so to step onto a stage alone (regardless of what form that stage takes).

Art, good or bad, propels us forward as a species, culture, tribe. Critics and audiences react to those beings brave enough to create, reveal, risk; critics can act as our course correction by reeling us in when the artist has gone too far or pushing when the artist hasn’t gone far enough, but it’s the creators who actually move us along and take us toward our potential.

Create (bad) art and release it into the world—the reaction is not your responsibility.

Your responsibility is to get back into the studio, kitchen, or computer and create more art, good or bad. It’s always worth it. It’s worth it for your sake because it frees up space within you, forces you to grow, and detaches you (hopefully) from the outcome—and it’s for the sake of the rest of us because we’re invited to see something we were missing.

Art gets us feeling, which gets us moving. Our fear of vulnerability, of revealing something about ourselves that risks getting us kicked out of the tribe is real and evolutionary, but it can be overcome when witnessed, appreciated, and sidestepped.

So create, because I promise you: it matters.

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 2 comments and reply