Check out Elephant’s Continually-updating Coronavirus Diary. ~ Waylon

Last week, as I was waiting for my mother-in-law to die of COVID-19, watching the mounting death toll around the world, and holding space for others to experience their emotions, I became aware that my internal organs were roiling in a confused pattern of constriction and expansion.

I started tracking my inner sensations—besides the agitation in my organs, my throat was constricted, and a subtle vibration was becoming a tremble that spread from my inner core to my extremities and even my jaw. Every opportunity to shed tears was a welcome release. An inner voice told me: “Shake, sweat, tremble, and cry!”

My training in Somatic Experiencing® reminded me that this was the natural response of a nervous system that is becoming overwhelmed. I remembered the comfort I felt when I first learned that crying, sweating, and shaking were not something to be ashamed of. I decided I wanted to share this with the world at a time when we are collectively holding our breaths as we watch the tsunami that is COVID-19 (or SARS-Cov-2) and its global personal, societal, political, and economic ramifications.

We need to let go of the idea that we need to “hold it together” at a time when we should be okay with “falling apart.” I promise you, our nervous systems are resilient, and after every “breakdown” there is a reorganization into more physical and emotional capacity.

We are living in unprecedented times, not because the world has not seen a global pandemic or a sharp economic downturn before, but because we are hyperconnected and constantly flooded by information from all corners of the globe. Our natural physiological responses to this invisible threat, consequently, are heightened. Our nervous systems are primed to fight or flee, but we are told to stay home and socially isolate, impeding the completion of the threat-response cycle and the release of intense survival activation. This leads to an urge to shut down that leaves us feeling tired, but wired, unable to sleep despite extreme exhaustion.

Because the threat is “invisible”—meaning it is either microscopic, as in the novel coronavirus, or imagined, as in the images evoked by news stories of death and catastrophe—we cannot orient to it. We might get stuck in a startle response—our eyes fixed, our shoulders raised and tense, our breath constricted high in our chests, our pelvic floor and abdomen lifted and tight. Or we might feel frozen in defensive orienting—our eyes darting but not finding the threat, mentally confused and emotionally ashamed about why we feel so overwhelmed.

It is then that our minds and psyches begin to project threat where there is not one in order to fulfill a naturally occurring fight-or-flight sequence. We begin to feel strong emotions like fear, anxiety, panic or restlessness, irritability, and even rage. Because emotions are bundles of sensations that our minds have given an emotional name to, we might feel as if our bodies cannot contain or manage these intense energies.

We are afraid or ashamed of the natural way in which our bodies release this sympathetic nervous system arousal—tears, sweating, trembling, and shaking—so we shut these down. Because the energy needs to be released in some way, we may pick fights with loved ones or strangers, primed to fight because we cannot flee. Or we shut down—immobilized, unmotivated, depressed—because we cannot express.

Let us look at how these natural responses of flight and fight might show up, and how we might get unstuck and respond more wisely rather than being reactive.

A flight response might show up as restlessness, jitteriness, and tension or nervousness in the legs. The cortical interpretation of this limbic experience is fear, nervousness, anxiety, and even panic. A fight response might show up as a tight jaw, tights fists, and upper body. The cortical interpretation or embodied cognition of these states is blame, annoyance, irritability, anger, or rage.

All these sensations might be scary at first, but tuning into the body, and giving it a different experience, might help reduce activation so we do not engage in unskillful behaviors like yelling at a loved one or abruptly quitting a job. Our bodies are intelligently wired with a release mechanism, and some of the ways in which the nervous system releases excess activation is through tears, sweating, trembling, and shaking. Let us first and foremost normalize and befriend these responses, and look for ways to invite them to complete, so we can experience the relief that comes once we return to a homeostasis or balance in our nervous systems and psyches.

How can we feel all our emotions and maintain emotional stability?

Here are some ways in which we can honor our body’s intelligence and support the release of these intense energies.

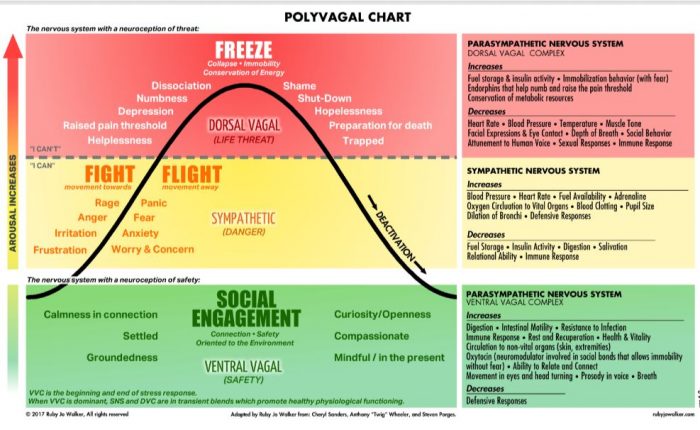

The polyvagal theory of the autonomic nervous system tells us that a human being’s first go-to when facing a threat is to socially engage. That portion of our vagus nerve that rules emotional communication is called the ventral vagal or social engagement system and connects to nerves in our face, ears, and vocal cords.

Social distancing may be limiting face-to-face contact, but we can still speak to a friend on the phone or via video. Tell a trusted friend how you feel—and feel free to shake, tremble, and cry! This vagal nerve engagement slows the heart and breath, reducing fight and flight.

Additionally, you can engage the ventral vagal system by:

- Vocalization: Om, chant, hum, sing, roar, laugh, growl.

- Facial expression: make faces playfully, half-smile, to reduce fixed expressions.

- Orientation: allow your eyes to scan your environment, let your neck follow your eyes, let your eyes find something pleasant and stay there, letting your eyes receive the pleasant image.

- Create a Zoom meeting with trusted friends to chat, do a joint activity, move, dance, express!

Reducing the flight response:

- Move your legs, feel the movement if you are walking, or make walking motions while seated.

- Do jumping jacks.

- Bounce on a physio-ball.

- Imagine yourself running in a beautiful setting, feel all the sensations in the image, and notice how your body responds.

Reducing the fight response:

- If your jaw is tight, gently open to where you feel the resistance, and then close your mouth; do several rounds of this until you feel your jaw is more loose.

- Grab a hand towel and twist with your hands going in opposite directions, feel the tension in your arms and shoulders, and feel all their strength go into the motion.

- Open and close tight fists; squeeze a tennis ball or other item that provides resistance.

- If an animal could express your irritation, which animal would it be? Roar and growl or just observe the image of the animal expressing what you feel unable to express.

Most importantly, as you engage in any of the above suggestions, allow any tears, heat, or trembling that arise! Let that release complete. Just track the sensations until you feel a completion, which is usually marked by a deeper breath or sigh. And then enjoy the state of balance, equanimity, freedom, or spaciousness.

Any of the above will move you out of a deep parasympathetic freeze response, but there is a time to honor the immobility response without fear, which is our rest-and-digest parasympathetic system. After all, our fight response to a microscopic virus is our immune system, and immunity is enhanced by rest and restore periods that do not require a lot of energy expense.

What can you do? Meditation, mindfulness, restorative yoga, and yoga nidra come to mind. But you can also color, knit, or engage in any other mindful artistic activity that calms and soothes you.

Our facial expressions and postures communicate to the cortical areas of our brain whether the environment is safe or unsafe. We experience limbically and interpret cortically. Let us be aware of what our bodies are communicating to our brains. Conscious changes in facial expression or body posture can—even if only temporarily—communicate that all is well in this one moment. Increasing heart rate variability, through shifts in breathing, goes a long way to enhancing our resilience and ability to bounce back from difficult moments.

Vagal flexibility translates into emotional flexibility, and we no longer need to get stuck in fight, flight, or freeze. A mind that can observe all these responses, without making a shaming story that perpetuates the freeze state, is the key to success.

So, shake, sweat, tremble, and cry! Do not feel ashamed to do so. You have a right to “fall apart.” It is a bleeping global pandemic!

~

Relephant:

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 2 comments and reply