“Feminism isn’t about making women stronger. Women are already strong, it’s about changing the way the world perceives that strength.” ~ G.D Anderson

~

We women often lose a lot before we finally get it back.

Some of us never get it back.

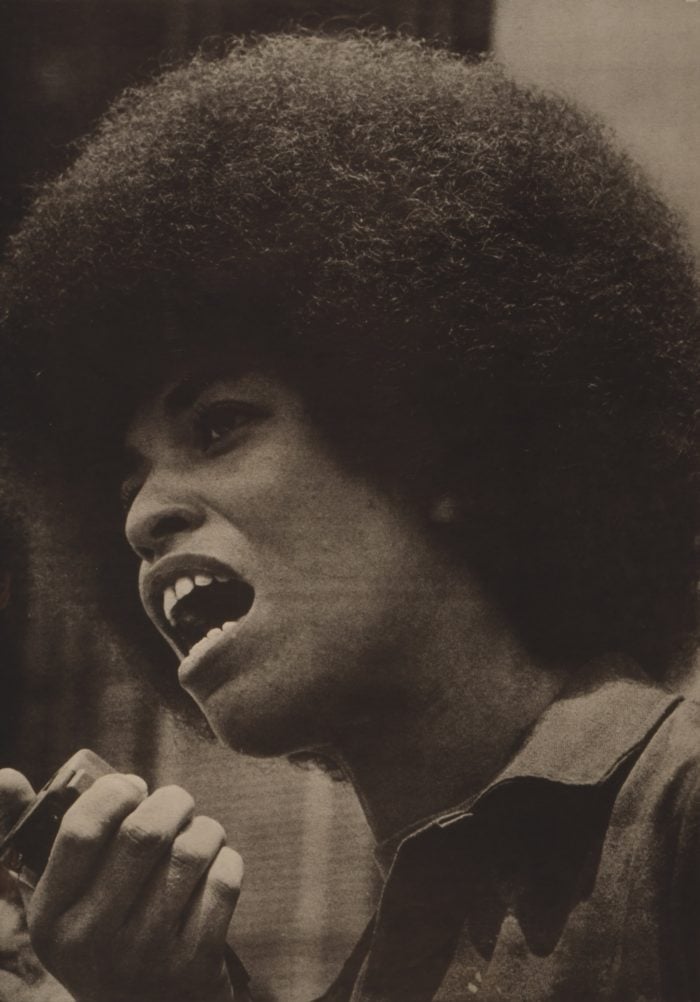

Who can forget the news story that cycled a few years ago—Maxine Waters repeatedly asserting into a microphone, “reclaiming my time” during a House Committee Meeting?

The phrase struck a chord with me. It’s used in the arena of political debate, but when that statement comes from a woman’s mouth, it’s a powerful one.

What was she saying, really? To me, she was saying: “My voice and my question matter. I will not allow you to twist, pontificate, gaslight, or filibuster your way to a non-answer.”

When exactly did I lose my time, my place, and my space? When did I allow myself to be steamrolled into submission? I can tell you for sure that it wasn’t in one fell swoop. It happened over time, slowly, from cradle to adulthood, and like trying to toss buckets of water out of a sinking ship, it was difficult to keep from going under.

I was sexually assaulted as a child. It’s a longer story for another time. No, I do Not Have Proof—but I lost my time, place, and space in the world in that instant. For years, I buried it by staying mute and shoving my true self to the side.

In first grade, I let a boy punch me in the arm on the playground. I “let” him do it, because I didn’t fight back. I allowed it to go unchecked, because when someone is violent, the person who endures the violence often internalizes fault, especially if it’s not the first time. To make matters worse, I accepted my friend’s explanation of the situation. She told me, “oh, that just means he likes you,” which is another way of saying, “it’s your fault for being here.”

My little friend meant no harm, but that event and her words pressed into my psyche the idea that because I was hit, I was “chosen” and the violence, disguised as attention, should not only be waved away as nothing to worry about, but permitted—ensuring its propagation.

In middle school, the father of the children I babysat made a pass at me on the ride home. He didn’t apologize for his behavior, or think it was wrong. He persisted, backing off only when I scrambled from the car.

And, he got away with it. I didn’t tell anyone that story until I was well into my 40s.

I knew that my firsthand account of what happened would have been met with denial and claims of a misunderstanding. Most likely, I would have been labeled a “liar.” The thing is, it never dawned on me to actually tell anyone, because of my ingrained awareness of what that result would be—and that is a powerless feeling. It’s a feeling that shrinks a woman into believing her voice doesn’t matter and holds no consequence in the world.

In high school, a teacher made lewd comments under his breath about my legs and breasts when I passed by him in the hallways. It was covert and creepy. Telling the administration would have been a can of worms, so I just accepted it as part of my day, and something to “put up” with. This perpetuated the idea that “grown men can’t help themselves,” and solidified my honed, internal coping mechanism—making sure I let it pass without “complaining.”

Out of sight, out of mind, and nothing to see here.

Make no mistake, the “men can’t help themselves” argument has always been a cleanup tool for people who don’t want to confront or rectify the problem.

In college, at a “T-shirt party” (where we women wore white T-shirts so the men could write anonymous messages on our backs with a sharpies; messages like “I want to f*ck your brains out,” and “please suck my cock,” and “grade-A meat”), I learned how to feel dirty, small, and expendable. Yes, I participated, but the thought process indoctrinated since childhood was: women are here for pleasure and procreation, so just play along! Men are in charge of who’s f*ckable.

As a white woman, I can only imagine the degree to which oppressive culture is—and has been—applied to women of color in my country, the United Sates, and throughout the world. The infringements I’ve endured are minor in comparison, but they are still relevant. The climb for women living under archaic sexist thumbs, or racist, religious rules is excruciatingly steeper and longer, not to mention fraught with peril and punishment.

Those who do not understand this climb, the ones who have us believing that inequality between the sexes no longer exists (or that we’ve done enough), are square pegs to the round, spiraling revolution that begins anew the moment a woman utters the phrase, “reclaiming my time,” which is to say: they do not fit.

Finding our place relies on our ability to rise, persist, and make our demands known. We can do this both quietly and in numbers. We can take back what we’ve lost in smaller, everyday moments, and we can “go big” in marching loudly alongside our sisters (and brothers) with picket signs and megaphones. We can continue to vote for the people who push for equality from top to bottom.

“Reclaiming my time” is about social change. It cuts through deflection, denial, lip service, excuses, and placating platitudes. The phrase is a power grab for women especially, and it works beautifully in just about every circumstance.

Women are people. Feminists are not a special interest group.

Often, when we reclaim our time, we’ll endure a slew of labels. “Bossy” and “b*tch” come to mind. President Trump himself refers to Congresswoman Waters (currently in her 15th term) as “wacky,” “crazy,” and “low IQ,” because he can’t contain her.

As a woman, I’ve had to learn repeatedly that in order to “reclaim my time” and place in the world, I must never acquiesce my power by letting sexist, suppressive ideologies go, just to keep things light and comfortable for all.

We must take command and right our own ships in order to create new narratives for women across the globe.

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 4 comments and reply