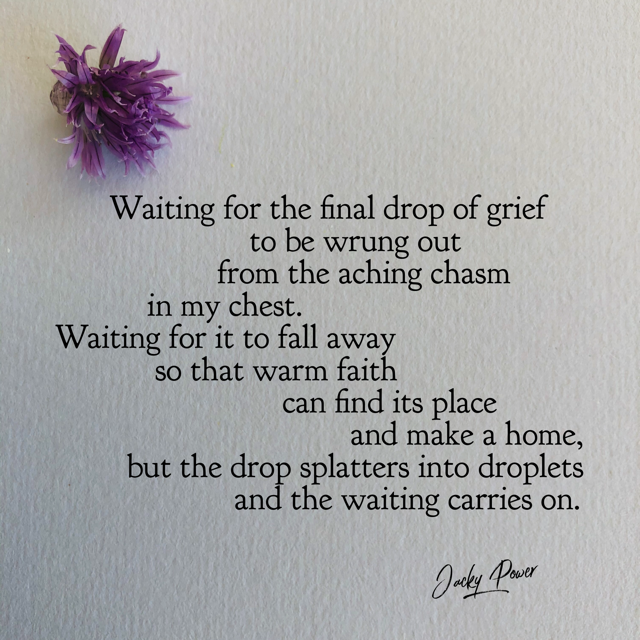

I didn’t realise it at the time, but when I wrote this I was writing about ambiguous grief.

Given our normal understanding of grief this can seem a bit of an oxymoron.

When we think about grief we often think about a definitive event that has been the cause of our loss – nothing ambiguous about that.

Yet sometimes the loss can be unclear, uncertain. Ambiguous grief is a term that was coined by Pauline Boss. It can be experienced when there is either a physical absence but a psychological presence (such as a missing person or divorce) or a physical presence but a psychological absence (such as loving someone lost to the throes of addiction or suffering from Alzheimer’s disease).

I wonder if it doesn’t just apply to people but to situations. Is it possible that Coronavirus has thrown us into collective ambiguous grief? Grief is certainly a term that is getting bantered about a lot as people share their feelings about the current situation.

I am not, of course, talking about those who are currently experiencing traditional grief due to the passing of loved one because of Coronavirus.

Even if we haven’t experienced this first hand we can anticipate the devastation of losing someone we love through death because, unfortunately, it is one of the solid guarantees in life. Whilst each loss will be particular in detail and depth, there is a collective sense of empathy for knowing that that will be tough and painful.

Ambiguous grief around Coronavirus though? What are we grieving?

So many small, individually insignificant but collectively pernicious losses:

The freedom of dropping my kids off to school and getting on with my day.

The spontaneity of popping down to the shops when I have forgotten an ingredient in the recipe I am cooking, or deciding to pop out to see a friend.

The sense of predictability, of planning things to look forward to

I’m no longer sure of what is expected of me. Now I’m a teacher to my kids, I can’t say for sure when I can do Zoom calls with clients as I need to balance it amongst what else is going on in the house. Should we stick to a routine or give ourselves some slack?

I’m not sure of what I expect of others: energies are low, so it’s not easy to know what people can handle.

Familiarity – I knew what to be worried about – my kids’ wellbeing, climate change, Brexit… Now there is another layer of concern and angst that is tipping my capacity to beyond full.

A time when I did not have to be vigilant around washing my hands, standing two metres apart, how many times I hear the word ‘unprecedented’ in a day.

Part of the troublesome impact of ambiguous loss is the way in which it is handled in society compared to traditional grief.

Ritual

When someone has died in ‘traditional’ circumstances there is the possibility of a ritual to help process the loss, bring in an element of a sense of control through the preparations and a sense of connection as such rituals are often done in groups. The structure provided by funerals, memorials or wakes gives one a sense of order, helps to regulate emotions and gives a sense of purpose in an otherwise anchorless time.

When we experience ambiguous loss this sense of ritual is absent. What is more disheartening is that this lack can increase the sense of fragmentation, shame and confusion.

I wonder if the ‘Clap for Carers’ that we engage in on a Thursday night is more than just an appreciation of those on the front line. I wonder if it is also not an unconscious ritual to process our grief. Whilst clapping itself is a sign of appreciation, and undoubtedly boosts wellbeing as it helps us to express gratitude, what about the ritual of us all going out at the same time on a Thursday night? Collective participation increases our sense of shared social identity.

Perhaps the Clap for Carers has spread so easily not only because we want to express gratitude but because it has become a way for us to process our ambiguous grief. A small moment where we can come together (socially distanced of course) and feel part of something again.

Norms of social acceptance

David Kessler, an expert on grief says:

‘Each person’s grief is as unique as their fingerprint. But what everyone has in common is that no matter how they grieve, they share a need for their grief to be witnessed. That doesn’t mean needing someone to try to lessen it or reframe it for them. The need is for someone to be fully present to the magnitude of their loss without trying to point out the silver lining.’ (Book: Finding Meaning: The Sixth Stage of Grief.)

With ‘traditional’ grief there is a social norm around what is expected of the grieving, even though the circumstances of death may be different. Elizabeth Kübler Ross identified certain ‘charactersitics’ of grief that have been well documented. These are denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. David has added to these characteristics with a more hopeful sixth stage of ‘finding meaning’.

These ways in which we process and seek solace in our grief may be blocked when this grief is ambiguous. The sense of loss may feel shameful, such as that experienced by addiction, or normalised, such as divorce. This type of loss is less likely to be tolerated by companions, friends and even family members. There may be a level of privacy to it that cannot be shared easily without the fear of judgment or fixing. It can mean that people get ‘frozen’ in their grief.

Doesn’t that ring true now? Don’t we secretly censor ourselves from sharing our sense of loss about things that seem trivial compared to those who have lost livelihoods or loved ones? Yet doesn’t that loss still hurt?

I’d argue that there has to be a space for it. David Kessler says: . ‘Every loss has meaning, and all losses are to be grieved—and witnessed.’ Appropriately, mindfully, sensitively, but grieved nonetheless.

Validation

Traditional loss is often legitimised by society. There is a collective consciousness around death and grieving.

Ambiguous loss results in changes to families, relationships, self identity just as traditional loss does, however, there is a lack of a collective narrative about how this loss is experienced and the impact that it can have.

When I wrote the poem above it was to process the shame I felt about the loss of a relationship. The reasons for that loss were private and complicated and when I had tried to share about it with people I felt misunderstood. It was a loss that could only be validated privately amongst a few select friends who understood the circumstances and my truth, but not a loss that is validated by society as a whole. The poem was a coded way of seeking that societal validation without giving my game a way so that I could process my feelings around it and gain some sense of closure.

So this is the point of this post. To invite a collective narrative about what appears to be a collective ambiguous loss. I know the impact of ambiguous loss. It is pervasive, shameful and confusing. I don’t wish that on anyone so I hope we can open up a conversation about our collective ambiguous loss. One which, hopefully, can be approached with kindness, generosity and understanding.

Read 0 comments and reply