There are kitchenettes on the oncology floor at Children’s Hospital in Boston.

They’re stocked with mini cereal boxes, Hoodsies, applesauce, juice, bread, and packets of peanut butter and jelly. Often parents have quick conversations about counts and cancer and the leftover McDonald’s in the refrigerator that we all share.

I can’t remember the names of these parents, but I always remember what kind of cancer their kid has. To me, they’re: the brain tumor mom, the Wilms sarcoma dad, and the leukemia mom who refers to her daughter’s cancer as “the garden variety” (I had to Google what that means because I wasn’t sure).

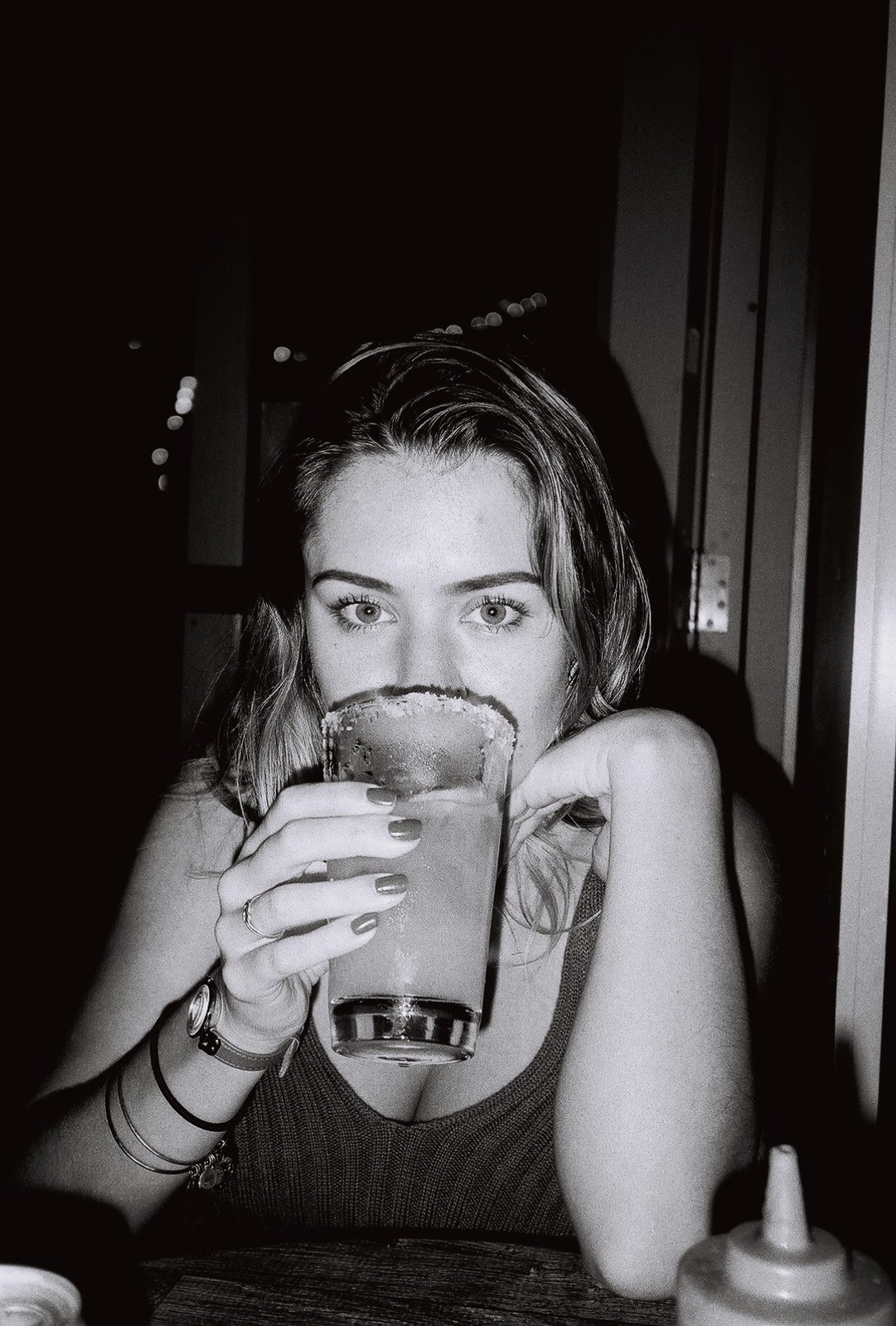

All day I looked forward to drinking vodka. Through the beeping machines, doctor visits, medicine attempts, and reactions to this drug or that, I comforted myself that at the end of it there will be vodka. I justified drinking as a reward for making it through the day. I told myself that I couldn’t “do cancer” without help.

Vodka helped. It allowed me to fall asleep. It allowed me to breathe without thinking about it. It allowed me to read books to my four-year-old daughter, Emily, at night and enjoy it. It signaled to my brain that it was the end of the day. It shut down the part of my brain that ran wild with thoughts of chemo, line infections, blood transfusions, and counts. It made me feel more like me, which I know wasn’t real, but I didn’t care because it felt real.

I waited until the nurses changed shifts at 7 p.m. and used their change of shift as my change of shift. I transitioned from a stressed-out-cancer-mom to a relaxed-loving-mom. Most of the time these two operated independently, so I was relieved when it was time to change shifts. I was careful to drink just enough to feel good and not too much to feel bad. A good buzz but not drunk. I had work the next day. Hospital mom work.

Once in a while, I thought about what someone from the normal world might say if they knew that every time I left for the hospital I packed water bottles filled with vodka. Her kid has cancer and she’s bringing vodka to the hospital? The thought was enough to keep my way of coping a secret.

I watched how other parents coped in the hospital. Some gained weight. Some lost weight. Some stayed on their phones all day. Some played solitaire. Some shopped online. Some walked the hallway. Some Googled their kid’s illness until they found research that allowed them to sleep at night.

I judged none of them. Because I understood. I drank vodka.

As I watched the moms and dads on the pediatric oncology floor, I felt guilt for the times I judged others during their time of crisis. Their divorce, their affair, their bankruptcy. I judged them as if I knew what they were going through. I would never…drink, gamble, shop, eat, or work in excess. I felt foolish. Foolish for judging them and their way of coping during their crisis. It was humbling. Cancer cured me of judging.

I didn’t want to need vodka every day. I wanted to be able to be present without it. I wanted to be able to snuggle with Emily at night and rub her back without taking little sips of what looks like diet coke. But the reality of what was happening was too much to process. She was so skinny that her bones popped out of her spine. And during her first transplant, the chemo she was given was so toxic that I had to wear a paper gown and gloves so the chemo can’t seep from her skin to mine.

On New Year’s Day, she needed emergency surgery to drain seven ounces of liquid from her heart. It seemed that something big happened every day. Vodka helped me overlook what I couldn’t when I was sober. It blurred what was clear.

Emily had cancer. She could die. It gave me fake strength and false assurances. I knew they were fake and false. But I didn’t care. Because when I was sober I had no strength; only painful assurances that made me unable to breathe.

Drinking fixed that. Except on big days. On those days, I had a tendency to drink more, because there was more pain. Drinking more makes everything more.

Emily was scheduled to be in the hospital for a round of chemo on the fourth of July. I was devastated and angry long before she was admitted for treatment. The fourth is like Christmas, only better in my family. My parents, three siblings, and their families, and friends gather for a day that we look forward to all year. My dad gets up in the middle of the night and puts chairs out for the town parade in the morning. We have lunch at my house. We go to the beach. We have a cookout with sparklers. Everyone gets along. It’s just about perfect.

When Emily was admitted a few days before the fourth, I brought my bad attitude and plastic vodka bottle with me. I reminded myself that I was helping Emily get better. That we’re exactly where we were supposed to be. That we would be at the parade next year. That next year would be the best fourth ever!

But then I immediately thought, We’re not supposed to be here! We are supposed to be picking out red, white, and blue shirts, and making Oreo bars! I wanted to change where we were and what we were doing. I wanted to do something to fix it. But I couldn’t.

The nurses on the floor tried to make the holiday more festive by handing out red, white, and blue beads and small flags. I could find nothing festive about a day spent in the hospital when everyone else was at the parade or the beach, and we were supposed to be with them. I felt guilty for my resentment toward Emily’s cancer. I’m a horrible caregiver. I’m an even worse mother. The good mothers are putting on beads and making flag pictures to hang on the windows. I was sulking.

We shared a double room with a girl who’s Emily’s age and has leukemia. Her mother was sweet and friendly. She apologized for everything. None of which she has any control over.

She asked if I wanted to join her on the rooftop to see the fireworks that night. She told me it’s one of the best places in the city to see them. Part of me wanted to go because it seemed celebratory and possibly fun. But a bigger part of me wanted to be miserable, so I declined. I told her that I didn’t want to leave Emily alone because she had a rough day. That she needed me and I didn’t feel comfortable leaving her. Part lie. Part truth.

I ordered Bertucci’s, took a shower, and pulled out my water bottle of vodka while we read. I didn’t dilute it. I took sips from the bottle. I was aware that this was risky but the voices in my head screamed that they didn’t care. The first few sips allowed me to accept that we were in the hospital on the fourth. The next few sips make me question, What was I so upset about? So I drank a little more. And more. And then passed out next to Emily in her bed with the TV on.

The next morning I was dizzy and nauseous. We were told that as soon as Emily’s labs came back and looked good that we would be able to go. The normally lengthy and tedious discharge routine felt uncharacteristically efficient.

I wasn’t sure how I was going to drive home. I drank water and ate pita chips. I popped four ibuprofen. I laid next to Emily trying to muster the will to get up and put our suitcases in the car. My head hurt. I was annoyed at myself. I almost threw up on the way home. I rolled down the windows for fresh air, but Emily yelled at me that she couldn’t hear “Sleeping Beauty,”so I blasted the air conditioning.

My parents were at the house when we got home. I told them nothing. I went for a walk. I didn’t ponder drinking. I pondered cancer. I wondered how long it was going to be a part of our lives. And how long I would feel alone. I wondered if I’d feel this desperate forever.

After my awful day, and all of my thinking, I drank again that night—because that’s what I did. But this time I drank just enough to make all of my ponderings go away so I could fall asleep.

My plan was that I would stop drinking when Emily finished treatment. It will be easier to stop drinking, because everything will be easier. With everything easier, I would not need to cope. I would be happy and free from cancer. Our lives would be almost perfect.

But this didn’t happen, so my plan fell apart.

Our lives after cancer are harder. I have anxiety that her cancer will come back. I want to be doing something to keep the cancer away, but I’m told that there’s nothing to do. Just wait. The days we wait for her scan results take years off of my life. The projection of what her life will be like makes me angry. Her physical therapy, speech therapy, hearing aids, damaged kidneys, leg braces, medicines, IEP concerns, and social well-being make me weak.

I needed to be strong to stop drinking, so I waited.

When I was home I didn’t add diet coke to my vodka. I preferred to consume it straight-up. I kept a bottle of vodka in the freezer and poured it into a glass that the girls used for juice. My vodka didn’t need a disguise when I was home. Disguises are for bad guys. Vodka was my good guy.

One night I noticed the amount of vodka in the glass. It was a lot. “You build up a tolerance,” my husband said. “Don’t feel bad about it.” But I did feel bad about it.

My god, am I an alcoholic?

I ran through a mental checklist of what makes an alcoholic. You need it to get through life, it’s very important to you, you can’t stop, it’s in excess—check to all of them. It was easy to ignore the checklist when Emily was sick, because she had cancer and it was justified. But now she doesn’t have cancer so it was harder to justify. There will never be a night for the rest of my life that I don’t need to drink. The reality of this was sobering. But not enough to make me change.

I saw memes of moms who drink wine every night, so I didn’t feel as bad. They drink and they didn’t even have a kid with cancer. I felt some shame that hard liquor was my drink of choice. There’s something more virtuous about drinking wine. More social. Less desperate. I didn’t talk about vodka to my best friend, my therapist, or anyone else because it was nonnegotiable and I was embarrassed that I continued to self-medicate. They wouldn’t understand anyway.

Vodka helped me cope with two things that I had no control over: cancer and my thoughts.

It had magical powers that made both go away while I was under its spell. It’s that good. I was convinced that nothing could make me feel better than vodka. Not therapy, or socializing, or meditating.

But there is something that made me feel better — something other than vodka — I just can’t see it every day.

Time makes me feel better. Every minute, every day, every year helps me feel a little bit better.

I’m unaware of this because I’m in a rush to get “it” all over with. The cancer, the anxious mind, the fear. I’m not patient and time requires patience. It’s not measurable from day to day, but it adds up month by month, and year by year. The gift of time allows me to resist thinking that Emily has relapsed every time something on her body hurts.

I remind myself, “Sometimes kids get headaches and it’s not a brain tumor.” I react. Not overreact. This is big for me and a gift of time. I stopped believing that it’s up to me whether Emily lives or dies. That I’m not poisoning her if I feed her a pepper that isn’t organic.

Time helped me realize two things: I want to protect Emily from pain. I cannot protect Emily from pain. It’s terrifying and oddly liberating. But I continued to drink because the thoughts and the cancer are still there.

One day, I got sick. Gradually, I got sicker and sicker. My stomach hurt. I had headaches. I couldn’t get enough sleep, or I couldn’t sleep at all. My face was puffy. I became frustrated at doctors who told me I was fine. I cried in my room.

Every night, I debated whether or not I should drink, because I knew it wasn’t helping me heal. But I also knew that the thought of not drinking made me panic.

For months, I continued this nightly battle of should I or shouldn’t I? But on a particular night near Christmas after taking four ibuprofen for a headache I’d had for days, I made the decision. I am not drinking tonight.

The voice in my head that usually cheers for booze whispered that I needed to be kind to my body. Drinking every night is not kind. I was furious at this voice. How dare she? And yet I knew she was right.

In the shower, I was cranky. When I went downstairs, I was even crankier. This is it? I just eat dinner now? Nothing to look forward to? I pacified the racing uncertainty by reminding myself that it wasn’t forever—just tonight. That I’d make a decision about tomorrow night after I see how tonight goes.

I fell asleep with no vodka. I was shocked. And hopeful.

I reminded myself that it takes two weeks to break a habit. So for two weeks, I did not drink. I was miserable. The best, most exciting part of my day had been stolen. I wanted it back. I tried to make up for the thing that had been there for me every night for eight years. I ate lots of chocolate. I read. I went to bed early, because I was cranky and didn’t want to be around myself.

Physically I didn’t feel that much better. I considered that maybe drinking didn’t hurt my health. That I was denying myself a pleasure that I could be enjoying. But then I paused. I didn’t want to undo my hard work. I was proud of myself for doing something that I never thought I could ever do.

Some people train for marathons. I stopped drinking.

A month passed. And then another. I didn’t drink one night. It was anticlimactic. Surely not drinking would be a bigger deal than this. I thought that I would be elevated in status. Or that I would be a better person. More virtuous. More in touch with my feelings. That something would shift, and I would change. But none of this happened.

No one notices or cares. Except for me. The only one who’s proud of me is me, which is disappointing because it’s hard not to drink vodka, and I want people to praise me for it.

With reluctance, I accept that I need to be proud of myself. That I ran the marathon but no one is there to celebrate with me. And that’s okay, because I did it for me. Yes. I did it for me. I keep telling myself this.

During this pandemic, I’ve found myself thinking about vodka in the shower—my mind telling me that it would help me feel better. And that everyone is drinking so I should join them. A couple of drinks here and there isn’t a big deal. Right?

But I’ve held out.

Mainly, because having to stop drinking later seems harder than resisting drinking now.

If I’ve made it this far, I can make it until the end. I can ignore the cheers in my mind that encourage me to pull out the vodka.

I’ve learned that there’s no end date to my streak of not drinking. Just like there was no end date for my streak of drinking.

I did what I needed to do then. I do what I need to do now.

And that’s how we get through a crisis.

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 16 comments and reply