How a fearful day turned out to be my catalyst for reinvention.

It was the early morning of January 6th, 2014 when my brother called. Seconds in and sobbing uncontrollably, he painfully pushed out the words, “Mum’s dead.”

No doubt some fear the prospect of hearing these words, whilst they might be expected or even welcomed by others. In my case, my mum’s biosuit shutdown was sudden and unexpected, and this particular event found me entirely unprepared. Of course, there’s no way I could’ve known at the time, but her death was actually one of the best things that’s ever happened to me.

People die

Grieving is different for everyone. Just like everything else in this wondrous dimension we call the human experience, there’s no right or wrong way to do things. There is only your truth. Anyone who tells you different ought to know better, and to coin a phrase: what others think about you is not your business.

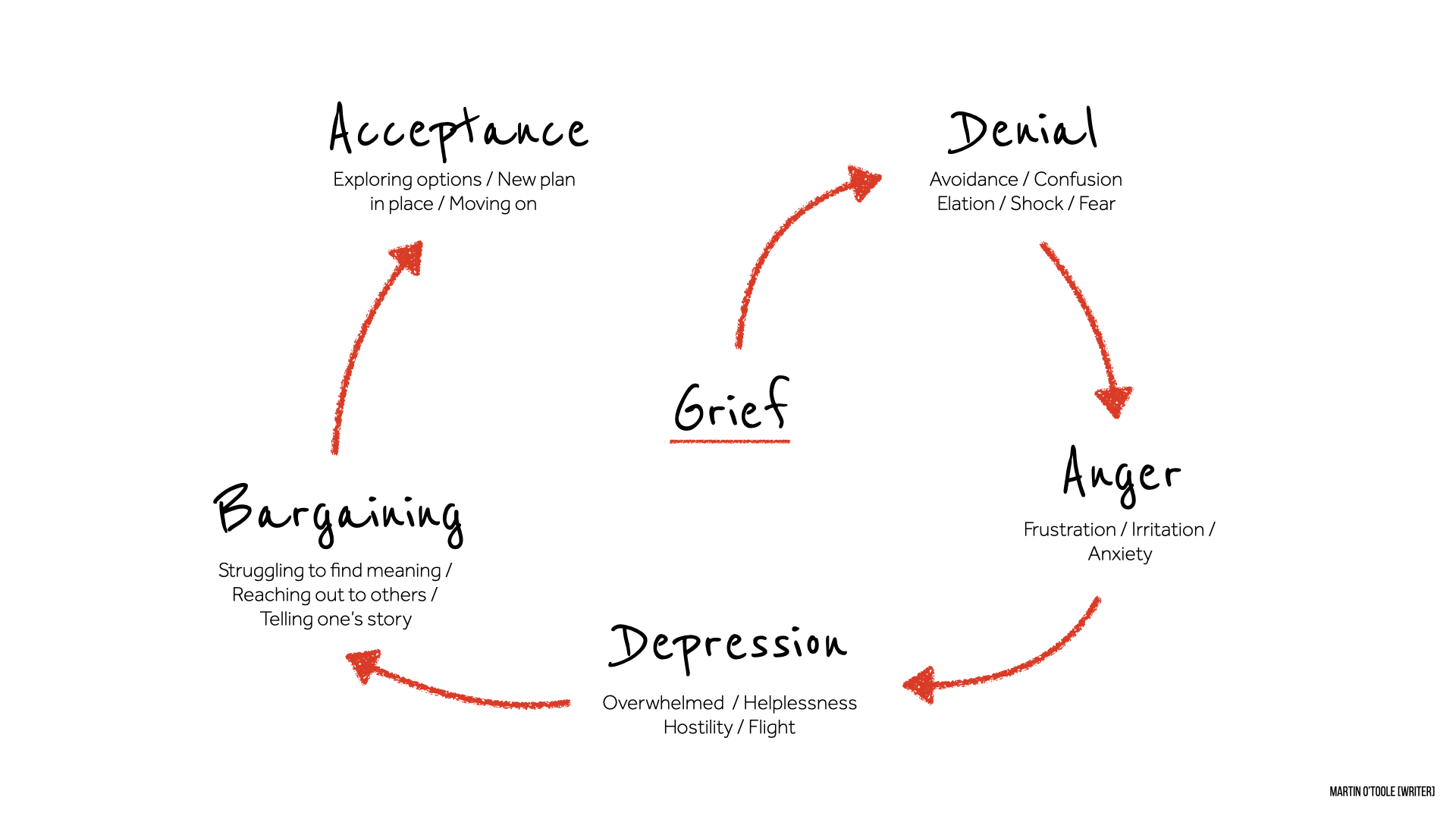

Psychiatrist and author Elizabeth Kübler-Ross knew a bit about death. She famously created the “Kübler-Ross model” that outlines the Five Stages of Grief. Perhaps it’s not news to state that when someone you’re close to dies, you’re going through a process whether you like it or not. Or rather, the event and your reaction to it will most certainly invite a process.

Any good therapist (my own included) will tell you there’s an exceptionally good chance that the death of a parent may well stir up suppressed emotional memories. If you’re open, good things can actually come from it. Unsurprisingly, when my mum died, a lengthy churning mess of grieving did indeed ensue. The maelstrom creating a monstrous rise of sedimentary pain and suffering from my very core. Countless traumas and unprocessed feelings that I’d spent years cultivating a fortress around began to spit and pop like a haphazard and bilious fireworks display.

“Pain is inevitable; suffering is optional.” ~ Buddha

Amidst all the anger and self-loathing, I was presented with a wondrous opportunity. I could smash, f*ck, and drink my way through fight-or-flight mode as I’d always done, or I could learn to surf the great wave of change that was hurtling toward me. I’d love to tell you about how I mindfully hopped onto that wave and Zen-rode it into Happy Cove for a barramundi steak and margarita, but that wouldn’t be honest.

In fact, I went well and truly off the rails. You see, my mum was an alcoholic. I’d turned out a first-class emotional mess. Not that I realised at the time, but I was an alcoholic too. Thus it was preordained I’d have to go the long way around this lesson—through fight, through flight, and as it transpired, through a near-suicidal event and lengthy self-loathing depression, which caused a great deal of dirty cloud of damage to those around me. Oh my, what a chirpy story this is turning out to be! Stick with it. There’s a happy ending.

My mum

In learning to heal myself, I now see past events and my relationship with mum with complete empathy and forgiveness. This wasn’t always the case.

My mum was a primary school teacher with a wicked wit, a terrible temper, and a penchant for sarcasm. She also had a love for words. As a kid growing up, I’d inquire about the schmancy vocabulary my parents used, and she’d always respond with, “You know where the dictionary is Martin; look it up!” Since this was a regular occurrence, I spent a fair amount of time with the Oxford English Dictionary, and undoubtedly these early interactions turned me on to the wonder of words.

At school, mum was loved, feared, and respected by children and parents alike. She taught a number of underprivileged kids, many of whom suffered abuse at that the hands of their parents. I never fully understood what it must’ve been like for her to care about those broken kids more than their own families did. Nor did I have any way of knowing that all the while she was broken too.

Mum’s having one of her turns

When she behaved oddly (which was often), my dad would just say “your mum’s having one of her funny turns,” and so, my brothers and I grew up believing our mum was just different. Scanning back, I have fragmented memories of those “turns.” Every day during the drive home from school, we’d have a brief and chatty ride whereby we shared tales from our respective days. Then we’d stop by the local off-license (liquor store) in the English market town of Pocklington, where we lived. She’d always park the car right outside, leaving my younger brother and I sitting patiently in the back. It was always a quick affair—in and out fast with a white plastic bag containing cigarettes and two extra-large bottles of Lambrusco wine. Home then, where my younger brother and I were plonked in front of the TV with a couple of biscuits each. She’d leave something slow-cooking in the oven and then slope off to her bedroom.

As cigarettes burned and the cheap wine flowed, she would sit in silence, or perhaps with the TV on. Often she would rant and hiss real vitriol. Or she would simply sob uncontrollably. I’d sometimes creep upstairs and kneel outside her room—silently spying through the gap in the door, as she sat in the dark with the curtains drawn even though it was still light outside.

In the early days, I was just a kid incapable of fathoming the complex emotional and psychological problems my parents had. I had no way of knowing she was a chronic alcoholic. As I got older and we saw less of each other, I used to wonder whether I could’ve been kinder, showing more empathy for her condition. Could we have had a better relationship if she’d truly opened up about her pain?

We had a strange relationship. There was a vacuous gap of understanding between us, created by her combined lack of availability and intimacy. My disdain was amplified by her dishonesty. Sometimes I loved her, sometimes it was pity. At points, my feelings grew to a livid pulp of unspeakable hatred. Now, as I consider her story with a heart full of love, I understand there were so many things I don’t (and didn’t) know about my mum. Which is okay.

The cider apple never falls far…

Ask anyone with an alcoholic parent how adamant they were about never following suit. Then ask about their later relationship with alcohol and other substances. I suspect their accounts will be far less black and white.

Whether you’re for nature or nurture, I know I inherently acquired my mental health issues in my childhood home. I was preprogrammed to have issues with intimacy and confrontation. Aggression, insecurity, and a wholesale mistrust of womankind were standard for me. Sure, I went on to cocreate all the drama in my adult life, but that was naturally never my aspiration. I vowed never to become anything like the role model I was then so “disgusted” by, but learnt how to drink to black-out anyway. By my early teens, I was a regular at police stations and hospitals, having some very close shaves with serious injury and even death. So as the years went by, my relationship with alcohol and drugs became noteworthy.

Aged 38 and in the throes of a colourful life story, I’d got used to my life’s dramatic and chicaning pace. Throughout those years, although life continued to present me with opportune lessons, I chose to ignore them as well as the people delivering them. If I’m honest, by the time my rampage was over, I’d caused way more damage to others (including my younger brother) than mum ever managed in her 73 years.

Little did I realise though that her death would mark the beginning of an entirely new journey. It would eventually become a wonderful journey of self-healing and reinvention. A journey inward.

You have two choices

Even though I unequivocally can state that death is a part of life; that all things are impermanent; and that refusing to consider this fact is at odds with the reality of the Universe…Despite all of that, for many, the idea of losing a parent remains absolutely unimaginable.

If you’re lucky, you and your mum (or dad, or both) are the best of friends. Perhaps they showed you love from the day you were born; listened to you, openly, and calmly communicated and invited the same, whilst teaching healthy lessons in boundaries and interaction. Perhaps, in this case, nothing ever went unsaid between you, leaving you with few to no regrets.

On the other hand, perhaps you didn’t have the picture of perfection I just painted, and so you still bear pain, which might well be resolved if you love yourself enough to share it.

Either way, the choice remains: say all that you ever wished to say, or do not. Fear the consequences of such honesty, or do not. Choices.

Woulda, coulda

There was a great deal I wished I’d said to my mum before she died. I wanted her to know how sorry I was for being so angry about her addiction. How sorry I was for saying so many foul things to her; how inconsiderate I was to wheel my suffering around like I was the only person in pain. I wished I’d had a better understanding of mental illness at a younger age—a better understanding of her illness. I wished I’d hugged her more instead of feeling disgusted by her. I wished I’d shown her more compassion during her cancer treatment. I wished I’d calmly and compassionately explained what her neglect had done to my brothers and me, and how the impact of her addiction had shaped our lives.

“Grief is just love with no place to go.” ~ Jamie Anderson

Alas, I didn’t do any of that, and then she was dead. So I had no choice other than to deal with all that was unsaid and unanswered, all on my own. Whilst I now realise how perfect my route and its lessons were for my growth, I can categorically confirm it was by no means for the fainthearted.

I’ve written about grief before. I’ve written about suffering too. My healing journey taught me that events are just events—neither good nor bad. How we respond to them is our real opportunity for growth.

I also learnt it matters not that I didn’t say any of those things to my mum. Just like the future, the past does not exist. All that truly matters is the present—the now.

Breaking the cycle

So August 9th, 2020 will mark two and a half years of my sobriety. Notwithstanding the miraculous effects this has had on my physical and mental health, the additional mindfulness practises I’ve adopted have completely changed the way I think, feel, and communicate.

My mum and I didn’t talk. None of us did. We learnt to keep secrets and to bury pain. Yet these days, I’m so happy to share my vulnerability that I write unfettered tales about my human experience and post them on the internet in the hope they might help others.

I’ve changed. I overcame my fear of loss and my focus on attachment. I surrendered to change and thus to the flow of life—a process that brought with it a wonderfully unburdened feeling of freedom and reinvention.

Giving up the ghost

No one’s healing journey is the same. For me, it all started on that rock-bottom day in 2014, then meandered and evolved from there. The biggest milestone was when my younger brother and I repaired our friendship, which had been stone-dead for eight years. He forgave me for things that others never could. In spite of the harm I had caused my younger brother, he went on to become a deeply considerate and loving mentor to me. Perhaps the best way to summarise this series of events is to remember a time in late 2018, as I thanked him for supporting my aspirations to change. His simple response was “Healing you is healing me, Martin.”

Well, I went on to make those huge changes. Having begun with my diet, I then considered my environment. Amidst it all, I discovered the unequivocal beauty in daily meditation. In the past year, I’ve added yoga, sound healing, plant medicine, and breathwork to the list of regular healing therapies. There’s a story I must one day tell about Holotropic Breathwork, but it’s not for now. Last year, during one such session, I came face-to-face with my mum. We stood together in peaceful unity and she smiled at me. As I forgave myself and asked for her forgiveness, she told me there was nothing to forgive and that she was proud of my reinvention. Then as we hugged, my cathartic sobbing released decades of pain. It was beautiful. It was my “goodbye.”

“Every time I meet more of myself, I can know and love more of you” ~ Yung Pueblo.

Of course there’s no exclusivity in losing a parent or dealing with alcoholism or an abusive upbringing. We all have a story and we all carry emotional baggage as a result of the story’s events. Like all other life events, even the most cataclysmic come hand-in-hand with opportunities for growth. Zingdad says: “If you can’t see the perfection, then you’re standing too close to the picture.” I get that seeing this perspective might be easier said than done, so perhaps for now just trust me when I say that everything is perfect.

I’m change; I’m kind of inevitable

Continued suffering in the Drama Triangle is the preference of some (and I respect their choice). For others, a different story calls, as it did for me. There were so many good reasons to leave my old life behind, yet there were none to argue against spreading my wings like a phoenix, around this amazing blue theatre of experience we call Earth. So I’m currently residing in Bali. Part of this massive life transition involved me following my dream of becoming a writer. Funnily enough, I’ve just finished my first screenplay, which I’m very excited about sharing with the world.

We have a curious relationship with death and loss. For me, it was linked to fear and a deep lack of acceptance. Even though I know what I know now, I wouldn’t do it any other way. Sure, as things worked out, I had to make the tougher choice of reconciling our relationship without mum being around. Though in that painfully deep shadow work, I met aspects of my self I never would’ve met otherwise.

Parents die. Pets die. Friends die. We all die. Impermanence is the one Universal constant. I suppose the only real question is: how ready are you for the inevitable wave of change?

It’s the elephant in the room for most of us. That social taboo we’re discouraged from discussing. For me though, acceptance and overcoming my fear and loathing of change at this level was what transformed my life forever.

I used to see everything as a battle, as a race or competition. I’d constantly compare myself to others, constantly berate myself for not having achieved this thing or not having done that. And because my heart was so closed to love, this focus on doing became all that I had. Funny how I finally worked out the point was to be—by being human.

I read this quote (author unknown): “It’s a journey. No one is ahead of you or behind you. You are not more ‘advanced’ or less enlightened. You are exactly where you need to be. It’s not a contest. It’s life. We are all teachers and we are all students.”

Perhaps this resonates? Or perhaps not! Choice.

We are at various points of our journey home. Some of us are at the beginning, some in the middle, and some, closer to the end. Our experience and perspectives reflect where we are on that journey. With this in mind, everything is as it should be. Everything is perfect.

Change brings lessons if we’re open to learning. That’s just it, I suppose. One cannot be willing to hear this without first accepting there is more to learn. That’s a beautiful aspect of the human experience. We are here, in this realm of separation, to learn to love. If we can grasp the concept of unconditional love in a world full of suffering individuals, then I suspect we can do truly anything, anywhere.

And the more places we go, the more people we meet, the more stories we subsequently interact with. Each of those people living their own story, each of them at their own perfect point of understanding; each of them with something to teach us—if we are willing to learn.

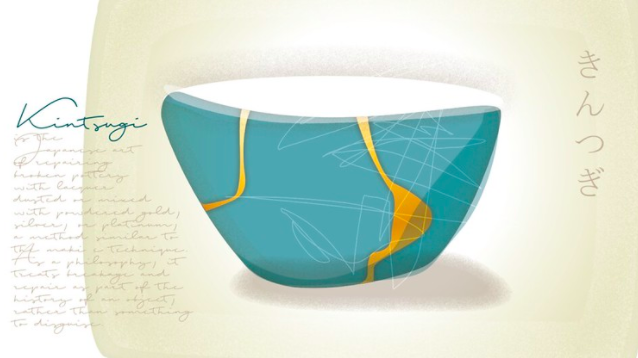

There’s no avoiding the fact that pre and post my mum’s death, I caused a lot of pain to others and to myself. Those events were lessons for all of us though. I suspect we’re all different as a result—I know I am. I put myself back together differently this time.

For me, it was a simple choice, and one I’m grateful to myself for making. You see, I’m only 44 years old, and I got another chance at life! I can’t tell you how invigorating it is—how excited I am to embrace such change. All of which began that cold January morning when my brother called. That event which I once considered to be bad.

Read 6 comments and reply