“Why are these protesters so angry?”

“Why do they have to be violent and tear things down? I know they’re upset, but there are other ways to do things. This isn’t doing any good…”

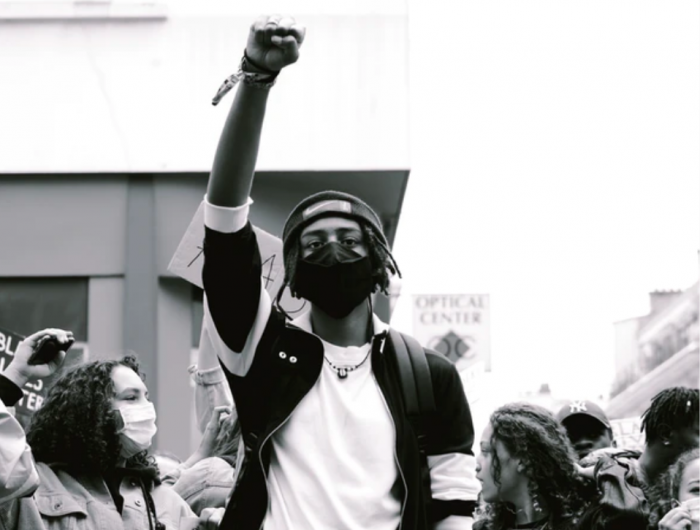

These are some of the sentiments that have been carelessly thrown around over the last month, since the killing of George Floyd sparked global unrest. The racial discourse surrounding these events has been extensive, and cannot possibly be summarized comprehensively here.

However, there is a central premise in the above statements that is rather misguided. Sure, people are angry, but aren’t they kind of overreacting?

Aside from its racial insensitivities, this kind of thinking exemplifies that many people simply may not recognize a basic distinction in the human experience: the difference between anger and rage.

I’ve heard many persons dramatically rant about their “anger issues” and how they’ve struggled with them for ages. Hell, I’ve had my share of them too. But in order to come to terms with these emotions, we must understand them in all their glorious ferocity.

Anger happens on a daily basis. It is often triggered by something in our environment and is usually fueled by other feelings, such as fear, hurt, or grief. But it exists on a spectrum of varying intensity and there is a marked difference between anger and its older, stronger brother, rage.

Anger is the parent who’s asked their kid to come to dinner five times already, but they still haven’t shut off their video games. Anger is being cut off in traffic when you’ve already had a long, difficult day. Anger is your boss passing you up for a promotion even though you know you deserved it more than the person who got it.

Rage, however, rage is raw, visceral, violent. Rage is the woman whose body has been violated by one who has no regard for anyone’s needs but their own. Rage is the parent whose child has been needlessly gunned down in the classroom where they were supposed to be nurtured. Rage is the brutally abused child, now grown-up and finally stepping into his own power. Rage is the onlooker witnessing a man being killed in the street and knowing it could just as easily have been someone they loved.

Rage is the demon who sits beside me on a leash, ready to fight for my right to exist and be seen. And the fire it breathes is all-encompassing, all-consuming, ready to engulf everything in its path. The fires of rage reflect the spark of the divine within us, the wrath of its destruction issuing justice in ways that our civilization’s flawed rules and regulations could not. It does not care what is procedurally or politically correct, and civility and decency are its casualties. Our collective rage has been unleashed, and the world is witnessing its repercussions.

But rage must be revered, for it is always borne of pain. It is the pain you feel when your humanity has been dismissed and disregarded. When your dignity has been stripped and your inherent worth stolen from you by one who abuses their power.

This kind of pain stretches beyond basic sadness or superficial anger. It touches us at the very core of our being, and leads us to discover the truth about ourselves: that regardless of how the world treats us, somewhere, deep down in the vast recesses of our souls, we know that we are supposed to be worthy. When that worth is stripped and that truth is disregarded, we can lose ourselves, either to the fires of rage or to the chasms of depression.

So where do we go from here? What can we learn from this? And how do we begin to address something as intense and primal as rage on a grand scale?

We have to honour the pain, grief, and suffering that arise from the loss of one’s humanity.

To do any less would make us inhumane. We have to honour this suffering on a personal level, hand in hand with brothers and sisters from the Black community. We have to honour it as a society, in our structures, systems, institutions, and language.

This is why political platitudes are not enough. Thoughts and prayers do not put out flames. Only acts of service and acknowledgement that are rooted in compassion and understanding, can begin to address the collective pain that whole communities of people have experienced. And a commitment to change must be demonstrated, not just discussed.

We also have to remember that what enrages us reflects what we value most. We forget that people are marching in the streets by the thousands because underneath all the rage, at the very center of the cause, is the value for human life in its every form and iteration.

We are enraged because we love. Because we know that George Floyd could just as easily have been my brother, uncle, partner, friend, or neighbour—and we want our neighbours to be loved the way we want love for ourselves.

So no, I’m not angry. I’m f*cking enraged.

~

Read 0 comments and reply