Yoga is for everybody—let’s establish that right off the bat.

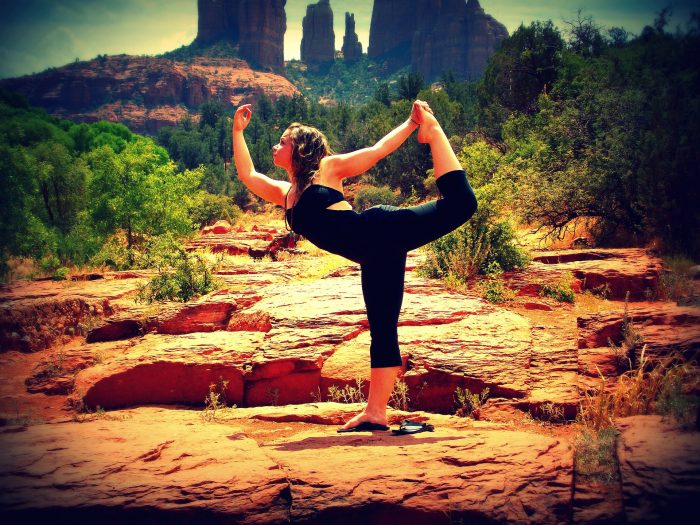

If you go through all the #yoga posts on social media, you’ll see a lot of perfection. Perfect bodies, perfect poses, perfect angles, perfect lighting, and so on.

While it’s great that people use their platforms to promote the practice, it can be a little intimidating—romanticized, even—and the emphasis on perfection almost takes away from what yoga is really about.

Yoga isn’t about perfection. It’s about harmony and taking a break from the pressures of daily life to reconnect with yourself and the universe. It’s about rejuvenation—mental, physical, and spiritual. That’s why it’s universal in its appeal.

By tracing its evolution over time, you’ll see that yoga is more than just an exercise. At its core, yoga is a spiritual exercise meant to help guide you to a higher state of consciousness and connect you to your innermost self.

The Origins of Yoga: A Brief History

Yoga, as a spiritual practice, has existed for over 5,000 years. According to myth, it originated with the god Shiva who, after attaining enlightenment, shared his knowledge with seven sages who then spread that knowledge across the continents. It rooted most deeply in India, where it was implemented into the culture and evolved over time.

The Mahabharata, an ancient Indian epic, tells us that the purpose of yoga is “the experience of uniting the individual with the universal Brahman,” and in a subsection called the Bhagavad Gita, explains how yogic action, devotion, and knowledge each play a role in attaining moksha—a form of enlightenment.

Enlightenment is a bit of a catch-all for various spiritual concepts, and its definitions range from self-realization to a release from the reincarnation cycle. Essentially, it’s a state of heightened awareness of one’s connection with the universe found through self-mastery and liberation from worldly attachments.

Around 400 BCE, an Indian sage named Patanjali compiled yogic teachings into a collection named the Yoga Sutras, consisting of hundreds of verses explaining its philosophy and practice. Patanjali reaffirmed yoga’s role as a spiritual exercise and went on to divide it into eight limbs, known as the Eightfold Path: abstinence, observance, yoga postures, breath control, withdrawal from the senses, concentration, meditation, and absorption.

While Patanjali formally introduces us to the asanas, yoga’s physical dimensions weren’t fully explored until the development of Hatha yoga, which dates back to the 11th century and is commonly believed to have been developed by a Hindu yogi named Gorakhnath.

Hatha yoga also began as a spiritual exercise, through which (it was said) one could achieve not only enlightenment, but also supernatural abilities known as siddhis. This is where the stereotype of the levitating yogi comes from.

Over time, Hatha yoga’s physical dimensions expanded to include bodily purification through proper diet, breathing exercises, and the performance of various positions known as the asanas.

At first, these exercises were seen as precursors to yoga’s higher spiritual goals, but eventually, Hatha yoga distanced itself from its spiritual dimensions, which made it more accessible and allowed it to flourish in India’s general populace.

As time progressed, various gurus and yogis continued to expound on yoga’s philosophy and practice. In the 15th century, a yogi named Svātmārāma compiled earlier teachings on Hatha yoga into a compilation called the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, which elaborated on various aspects of the practice—like the asanas, breathing exercises, meditation, and the flow of inner energies—in its four chapters.

In the mid-19th century, an Indian scientist named Nobin Chunder Paul published a Westernized study on the science behind yoga and the benefits provided by the asanas and breathing techniques after spending decades observing yogis.

Around the same time, an Indian prince in the Mysore Palace composed the Sritattvandhi: a compilation of 122 asanas, complete with detailed illustrations. Though it wasn’t found until the late 20th century, the Sritattvandhi dates back to the 19th century, suggesting that yoga had been established as a physical exercise well before then.

Yoga made its way to the Western world when Swami Vivekananda, a spiritual leader of wide renown, brought his teachings to Europe and the United States. His wisdom resonated with the populace, and yoga grew increasingly popular over the following decades. Following Swami Vivekananda’s example, many gurus and yogis migrated to the West and placed heavier emphasis on the asanas after being inspired by Western gymnasts.

Yoga’s Migration to the Western World

While Vivekananda was one of yoga’s biggest proponents, he rejected Hatha yoga’s emphasis on its physical aspects. Yoga’s asanas weren’t introduced to the Western world until an Indian guru named Yogendra created The Yoga Institute in New York in the early 20th century.

Yogendra sought to overcome the bias against Hatha yoga by collecting scientific evidence of its many benefits. Other yogis and gurus followed his example, like Swami Kuvalayananda, who published the first scientific study on yoga in 1924, and his student Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, who’s known as the father of modern yoga.

To promote yoga, Krishnamacharya spent the 1920s performing feats of physical prowess, like slowing his heartbeat and picking up objects with his teeth. After impressing the Maharaja of Mysore with his displays, Krishnamacharya was invited to teach yoga in the Jaganmohan Palace, where he was introduced to wrestling, Western gymnastics, and the Surya Namaskar. Finding inspiration in these practices, he implemented them into his own style of yoga.

Krishnamacharya spent the rest of his life passing on his teachings to various students, some of whom followed his example and helped promote yoga in the Western world. Two of his students are especially recognized for their contributions: K. Pattabhi Jois, whose development of Ashtanga Vinyasa yoga led to the creation of modern Power Vinyasa yoga; and his brother-in-law, B. K. S. Iyengar, who founded Iyengar yoga. Together, with Krishnamacharya, these three yogis (along with many others) popularized yoga as a form of exercise in the West.

As yoga spread throughout the West, it continued to distance itself from its religious sentiments. Critics denounce Western yoga for its departure from its spiritual origins, but these changes made it more accessible. Few of us are committed to the pursuit of enlightenment, and even fewer are willing to sacrifice our worldly possessions and desires. Many of us prefer to take solace in its practicality, and yoga feels much more inviting when we highlight its accessibility.

Critics also denounce Western yoga for its perceived superficiality—the same emphasis on bodies, lighting, and angles that we discussed earlier—but yoga (in part) has been about perfection from the very beginning, from pursuing enlightenment as the perfect state of being to the preciseness of the asanas.

Today’s yoga culture is simply a modern expression of the same sentiment. Like Krishnamacharya, Instagram yogis promote the practice by embodying the heights it can lead us to.

Looking beneath the surface, you’ll see that Western yoga still adheres to the original yogic sentiments. Enlightenment involves accepting one’s place in the universe, which is a precept of modern practice. Most sessions include time for meditation, with some instructors offering guidance on how to let go of stress, center ourselves in the present moment, and connect with the Self.

Western yoga continues to evolve along with our culture. Some practitioners include aspects of body positivity—further emphasizing the importance of acceptance.

By blending physical and mental practices, Western yoga still serves the same transformative purpose: striving for self-realization through mastery of the mind and body.

Instead of reaching for godliness or supernatural abilities, we try to find healthy ways of coping with our daily stressors—allowing us to operate from our higher ideals.

Too often, yoga is downplayed as just another exercise, but it’s deeper than that. Tracing its evolution over time helps us understand the philosophical pillars behind the practice, but it also gives us insight into the human condition.

Throughout history, people have looked for ways to both improve themselves and relate to the world around them. Time and again, yoga has proven to be one of the best tools we have to do so.

Next time you’re doing yoga, reflect on the multitudes of people throughout history who have walked down the same path you now find yourself on.

In this way, yoga becomes a tool to help us better comprehend not only ourselves, but the world around us.

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 6 comments and reply