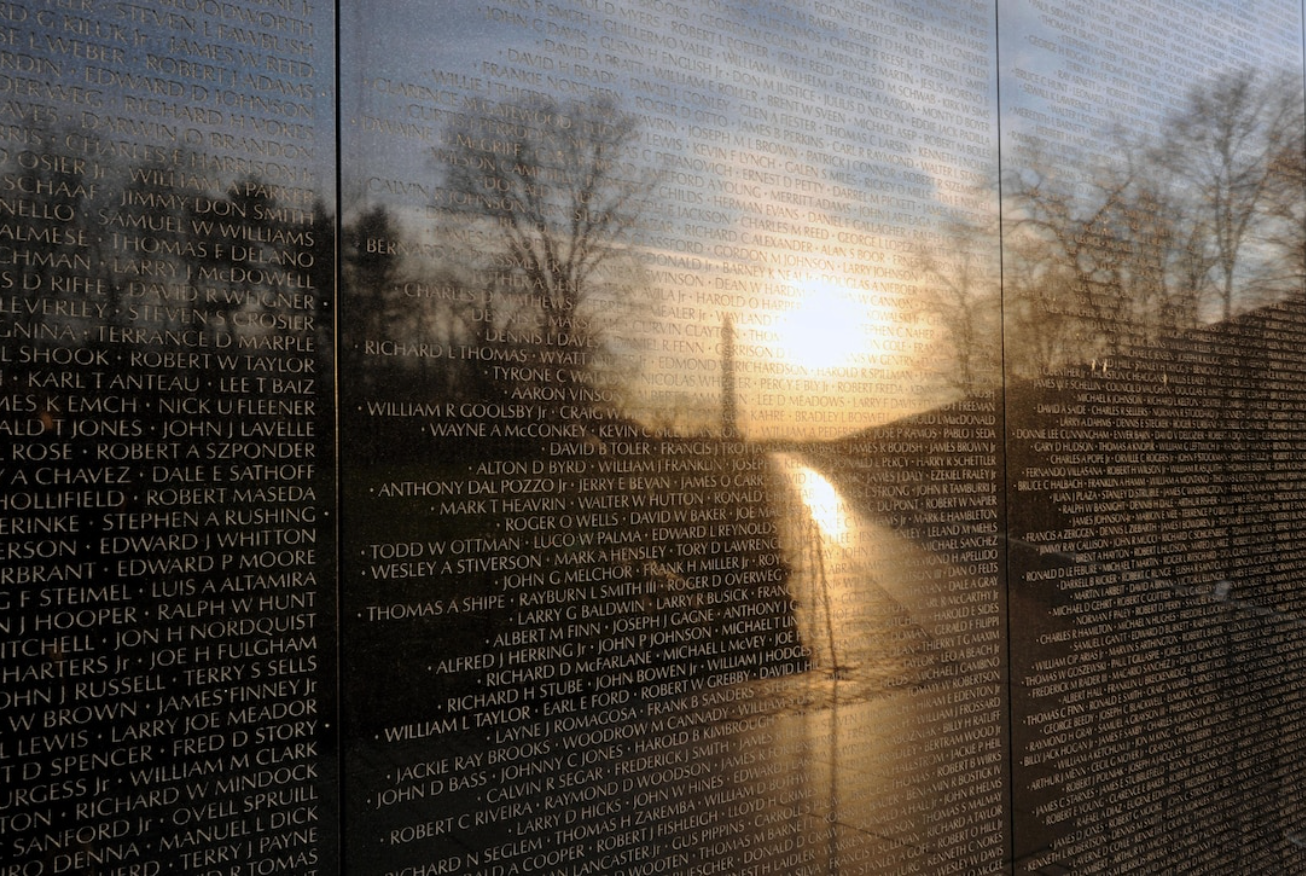

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial and the National September 11 Memorial & Museum were constructed with postminimalism that allows emotional content without forcing an agenda.

The visitor can feel the loss of life and choose for themselves how to reflect on the meaning they find.

Monuments are not only commemorations of historical facts on a timeline, or proof of who won, but like churches and cemeteries, present themselves to us in stillness, for us to integrate our shared grief.

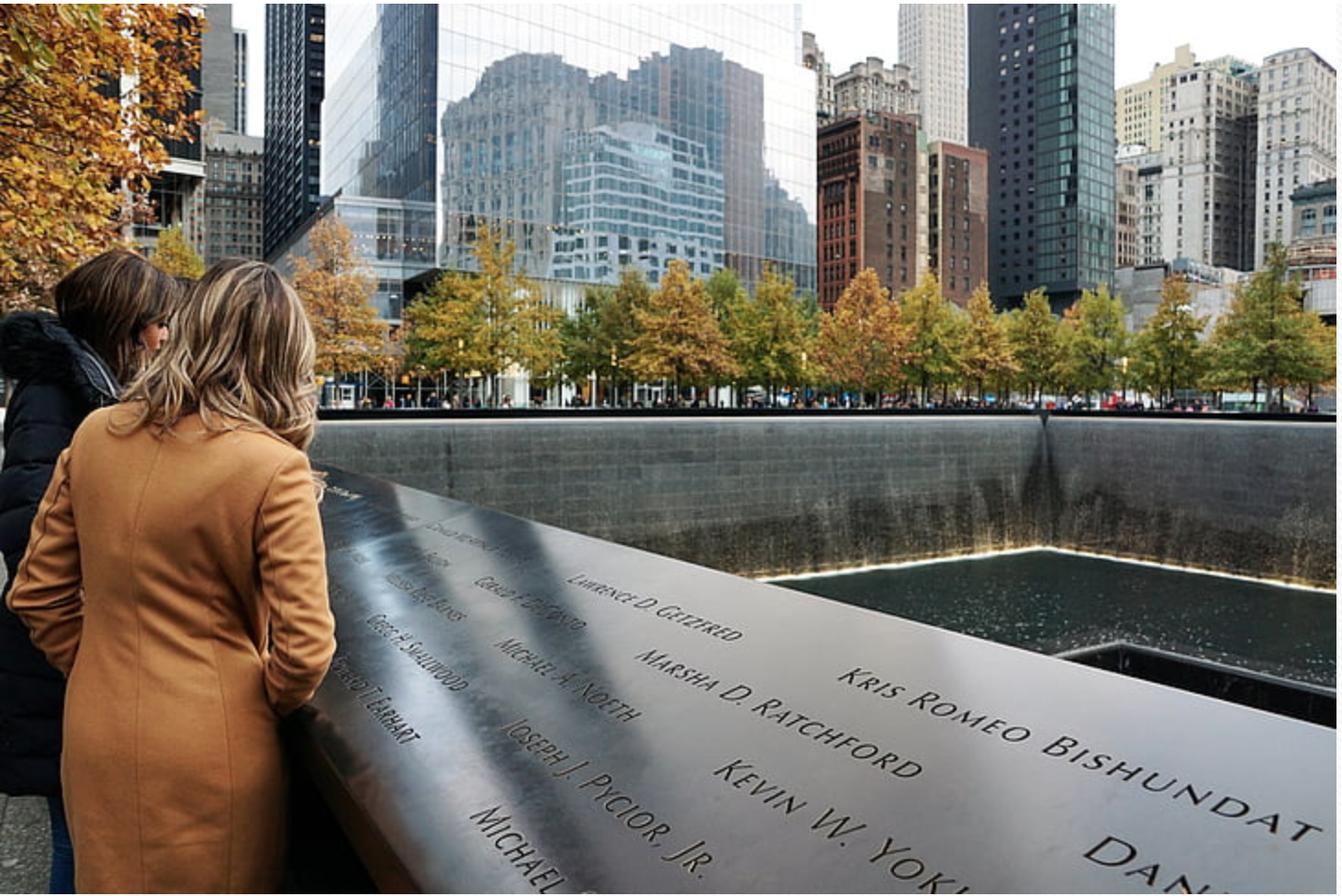

Michael Arad, the architect of the September 11 Memorial, intended it to be “stoic, defiant, and compassionate,” a complex intention, to say the least. The process of pushing against commercialization, of attending to the wishes of the deceased families, and of letting go of the initial vision, led the architect Arad to conclude after eight years, “I learned that you can accept some changes to its form without compromising its intent.”

We seem to need monuments—it is a dignified response to atrocious occurrences.

The Lincoln Memorial, which may be the most beloved American monument, was a response to the grotesque reality of the Civil War, the American experiment coming close to collapse soon after its beginnings.

But if we allow the stone architectural monoliths to do all the work of remembering, then we will be taken unawares by the sweep of history and perhaps folded into it as graceless and mindless dullards.

The United State of America can longer be called an ungainly child. She is, at least in her teenage years, energetic and brooding—dangerous, but still not without beauty.

These monuments draw our attention to intentional loss of life which seems to always caused by anger.

Anger can be a passion for justice; anger can be rage that the whole world is not conforming to one’s own desires.

Can we be living remembrances of the good spirit that built the Lincoln Memorial? Of such beauty as the Vietnam Memorial? Of such dignity and respect that built the September 11 Memorial & Museum?

Can I hold myself so that life—with which we are all animated most delicately—should be my primary observation and value?

In 1975, my grandmother experienced a fatal stroke beside me, on the day I turned eight. My father said to me, “She loved you very much, and she was a wonderful person. Now you can be like her and carry that on.”

By saying this, he assigned me to be a living monument, an honor to my ancestress. With his passing last year, I recognize the goodness in those ancestors as part of what animates me.

One way to experience the monuments from wherever you are:

Pull up an image of the National September 11 Memorial & Museum that touches your emotions—the Survivors’ Staircase is evocative.

Hold your gaze upon it lightly, and ponder without analyzing.

Offer words of intention, prayer, or connectedness.

Remain in silence for a desired time to hold the experience close.

Survivors’ Staircase:

Slurry Wall:

9/11 Memorial:

Lincoln Memorial:

Vietnam Memorial:

For me, the sound of quiet skies or an airliner overhead will always be a reminder of 9/11, a reminder to be grateful for peace, a reminder that not everyone wishes for peace, and a reminder to care for life while we have it.

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 3 comments and reply