I lost my younger sister to a rare genetic disorder called MELAS syndrome.

It’s a progressively fatal one at that. Six months lay between the time she was diagnosed and when she died. A mere six months. She’d declined rapidly; the last month of her life was far more rapid than the five months leading up to it. It wasn’t easy watching it happen so fast.

She was 24 years old at the time of her death. She’d spent her 24th birthday recovering from the surgery to “officially” diagnose her even though the spinal tap basically did the same thing. They just wanted more money. Money we didn’t have. Her life was full, her death was tragic, and what she left behind is what meant the most.

Her death also left me, my family, friends, and assorted other factors with a void only she could fill. A void that would be forever left unfilled.

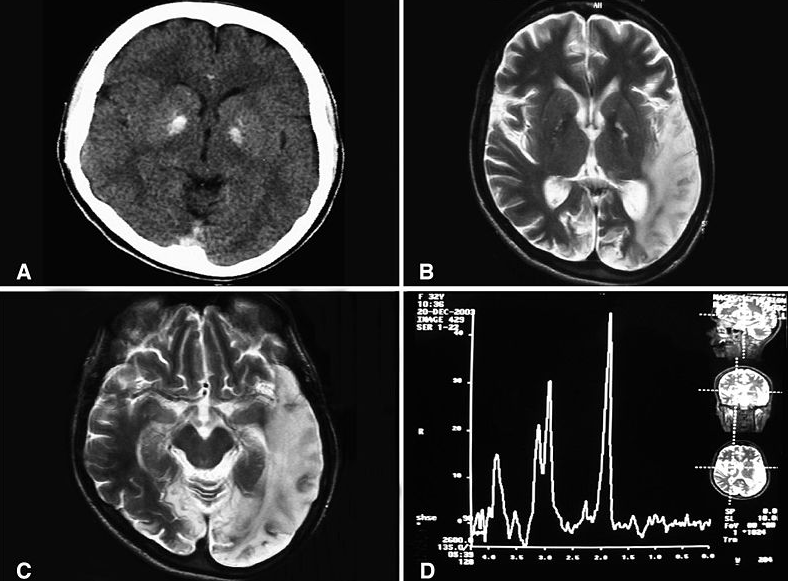

Mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, stroke, or stroke-like symptoms are the characteristics of MELAS syndrome. My sister had a total of three strokes as well as one bout of encephalitis. She hadn’t had anything related to lactic acidosis. Mitochondrial comes from the MtDNA, which comes from the mother. It’s ironic, considering our mother died from a heart attack and a brain stem stroke on September 1st, 2002.

At the time, she was a mostly healthy 43-year-old female. She had some health problems, none of which were fatal. She’d woken up on August 25th, 2002 not feeling well. By the end of that day, she was feeling far worse. She went to sleep that night and never woke up. She was declared brain dead the next day after our dad found her unresponsive and near-death. She died six days later on September 1st. It left my 13-year-old self as well as my eight-year-old sister without a mom. We’d spend the next 17 years having no answers as to what happened—until Rachel got sick.

Rachel encountered her only bout of encephalitis in March 2018, where she spent a week in the hospital. That July, 12 days prior to her 24th birthday, she lost vision in her right eye while driving home late at night from seeing some friends in Gainesville. She was in the hospital by that Sunday, July 22. It took three days for the neurologist to have an MRI done—she’d been going off a four-month-old MRI. The spinal tap, along with some digging from an interventionist, revealed Rachel had MELAS syndrome. The surgery was to “officially/formally” diagnose her.

Her death sentence had been sealed two weeks later on August 13th, when she had her second stroke. She’d had a seizure that morning. Her boyfriend had taken the car after dropping my dad off at work to go to a friend’s when I texted dad and told him what was going on and that I was calling 911. He’d told me not to because of Tyler coming to get him and that they’d take her to the ER. I told him we didn’t have time. Still, I waited and they whisked her off to the ER. They stabilized her and rushed her off to Shands in Gainesville.

The next six months was a harrowing journey of her decline. We watched her deteriorate every day. She had dementia by the end of October. By Christmas, she was sleeping most of the time. She couldn’t function anymore. I knew the day was getting closer that I’d find my sister long gone.

It was the annual family gathering at Christmas that was a test of sorts. We were there for more than two hours, which was her functionality limit. I knew she was worn out. I knew that the rest of the family likely knew this was going to be the last one by her demeanor. She was far weaker than she’d been in recent weeks. In many ways, I knew they knew.

Her time with us was limited.

Then it finally came: the day we found her. She died while everyone else was asleep. There wasn’t anything we’d have been able to do. Her death was an eventuality. I no longer had that shadow with me—not physically, anyway. Heartbroken and devastated doesn’t come close to the feelings I’d felt then, and now. My world ended when she died. I was lost without her. I’d been feeling lost for a while by the number of deaths I’d been through to this point, but I’d been thrown into a darkness that was darker than night with her death.

It’s been nearly two years since her death. I’ve felt lost the entire time. I’ve talked about her daily. I’ve had to tone it back because people feel uncomfortable with me talking about her so much. But she was part of my life for most of her life. So instead, I channeled all of it into writing about her.

I’d lost myself when she passed, and in writing about her, I found myself again in unique ways. I found that I can have a life without her and that being myself is something that’s possible. She had helped me along the way—like she often did in life. She always helped me see that I was going to be okay, in time, anyway. Even she knew it was going to take me some time to live with her not being there.

I found myself again by writing about myself and the things I’d been through with her transition. I let go of what I thought had to happen in life and just let life lead the way at times. I’d also found myself connected to life as a more fluid person—a person who wasn’t dictated by typical standards of society.

A shift happened when she died. Another shift happened the day I stopped letting societal standards dictate my life.

Even though it’s been a year and a half since she died, she’s told me more than once that it’s okay for me to go on with my life. That she’s always going to be with me. I’d lost my sister to something that was no one’s fault—not hers, not mine.

I’d lost myself that day. But in time, I’d found myself again.

~

Read 0 comments and reply