“There’s something very special about Himalayan children: their deeply rooted Dharma, their mindfulness, their caring and compassionate nature for all living beings, their capacity to open their hearts to others, and their ability to inspire others to do the same—all virtues embedded in their culture. And virtues we need more of in our modern world.” ~ Excerpt from A Story of Karma: Finding Love and Truth in the Lost Valley of the Himalaya

~

In 2012 my wife Chantal and I undertook an expedition deep in the Himalaya of northern Nepal, into a remote valley that had been closed off to outsiders for generations.

Our objective was to observe and learn through multiple lenses (photography, film, music, and art), capturing a moment in time from a people who had largely sustained themselves in much the same way for hundreds of years. Since the valley had been opened to the outside world, we were told that it would likely experience unprecedented and rapid change. With a dream to climb in the Himalaya since I was a teenager, I had a second objective to find and climb an unknown peak I had only identified in a photograph.

We understood that the area is a beyul (sacred valley), which according to Tibetan Buddhism, is a place of multiple dimensions where the physical and spiritual worlds coalesce. About them, the Dalai Lama has said, “From a Buddhist perspective [these] sacred environments…are not places to escape the world, but to enter it more deeply…Such places often have a power that we cannot easily describe or explain….[They] can encourage us to expand our vision not only of ourselves, but of reality itself.” Beyul or not, the experience in this Lost Valley of the Himalaya transformed my life.

After my plans to climb the unknown mountain were foiled and my dreams of climbing in the Himalaya shattered (we were caught in a snowstorm at 17,000 ft and my mule carrying my climbing gear ran off), I was forced to hunker down in the small village of Phu, one of the most remote village outposts in the Himalaya. It was here that a series of serendipitous events and choices began to unfold—events that would lead me to a little seven-year-old girl teaching English numbers to a group of students ranging from three to eight years old. Meeting Karma (the little girl) was the most profound encounter of my life—and one that would change the trajectory of both of our lives in ways we could never have imagined.

My new book, A Story of Karma: Finding Love and Truth in the Lost Valley of the Himalaya, recounts this journey, and the years that follow as Karma and her family, and Chantal and I have grown our lives together. In short, it is a story of human connection, love, and compassion amidst the complex dichotomies of our world.

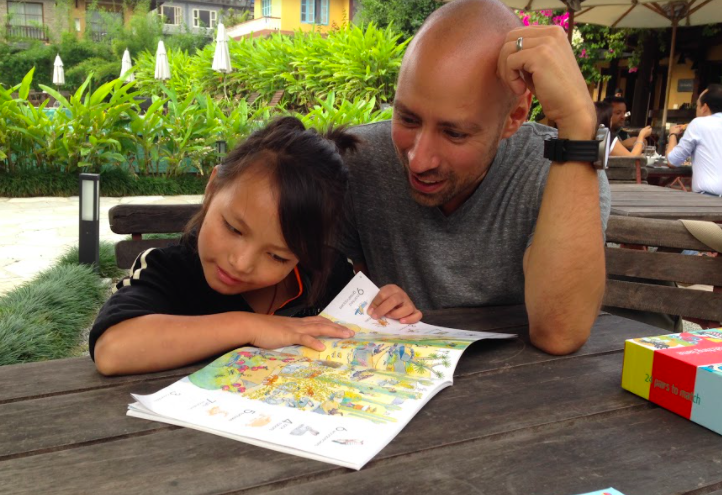

Following is an excerpt from A Story of Karma—part of a scene of one of our many visits to Nepal, or “family vacations,” with Karma, Pemba and their father Sonam. The scene speaks to several of the themes in the book—namely the influence of our modern world as it relates to traditional practices, and the values we’re nurturing in our children.

~

On our last day in Pokhara, we visited the International Mountain Museum. The museum has an impressive display of information about the history of mountaineering in Nepal, and about the geology and ecology of the Himalaya. Karma and Pemba found the display of climbing gear fascinating—the ice axes, crampons, heavy-duty mountaineering boots, oxygen bottles and masks, the thick down suits that make the climbers look like Martians, and all the other gear involved in scaling some of the world’s highest peaks. They’d lived among those peaks since they were born but never had any idea what was involved in climbing them.

The museum also has displays devoted to the people who live in the high mountain villages—people like themselves, in other words. As we passed one of the dioramas depicting village life, Sonam brought out his flip phone and began taking photos of the scene. It was a replica of a stone and clay house, just like the ones we saw in Phu and Nar, complete with an authentic mdong mo (a Tibetan butter tea churn), a dung-fuelled stove, and manikins dressed in traditional chubas. Sonam smiled at me and said, “My home.”

Something turned over inside of me at those words. It was hard for me to imagine what it would be like for someone to see his own way of life enshrined in a museum setting as something exotic—and possibly endangered. As we left the diorama and continued to look at the various displays, I couldn’t let go of this thought. I wondered what would happen to the semi-nomadic life that has sustained Sonam and his people for many generations, and to the village where they made their home. Once their children are educated and exposed to the outside world and its opportunities, will they leave their villages behind? Is their culture at risk of disappearing forever? Will their village become one of those abandoned ruins I’d seen on our trek?

Ever since my conversations with Sonam Dorje back in Phu, I’d been wrestling with these dilemmas, and they had become even more troubling to me once I’d met Karma and began helping her, and now Pemba, to get an education. But never had I been faced with them as forcefully as I was then, when I was confronted with the very real possibility their culture might be destined one day to be nothing more than a diorama in a museum.

However, what happened next brought a new thought to me. Near the end of our tour, we came upon a Tibetan Buddhist shrine hall, elaborately fashioned after that of a traditional gompa. Without any instruction or prompting, Karma and Pemba approached the shrine and with eyes closed placed their hands in prayer position, touched their hands to their temples, to their lips, and then to their hearts, while offering the Tibetan blessing, Namo Buddaya, Namo Dharmaya, and Namo Sanghaya (homage to the Buddha, the teachings, and the community). They remained there for a moment, in profound thought, with eyes still closed, before they stepped backwards from the shrine. I saw in that action that their culture and its traditions are something that will always reside within them. Then I remembered Sonam had said to me, the first time we met, that for him the most important thing was that his girls never forget where they’re from, never forget their Dharma, their way of being. I realized as I watched Karma and Pemba that, thanks to the way they were raised, they will not forget. It has become part of the very essence of who they are.

“There are some things that should not change,” I said to Sonam. I don’t know if he understood me, but his eyes seemed in agreement.

Through my experiences with Karma and Pemba, I’ve witnessed a deeper understanding of interconnectedness embedded in the culture and nature of Himalayan children; seeing themselves not as separate individuals, but as part of an interconnected web, helps inform their actions and behaviours, and fosters an overall greater sense of caring in the world. And even though we can find ourselves continents and cultures apart, I’ve learned that we can choose to foster the deep familial connections that run between us.

Honouring this connection is the greatest thing I’ve learned. No matter what happens, it will forever be a part of me.

~

Excerpt from A Story of Karma: Finding Love and Truth in the Lost Valley of the Himalaya by Michael Schauch. Copyright 2020. Published by Rocky Mountain Books. All rights reserved.

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 4 comments and reply