Before September swirls to a close, I’m sharing something for craniosynostosis awareness month.

Pretending I don’t know what my young daughter is talking about when she expresses concern about her facial difference will deny her experience. That phrase, “deny her experience”, is cliche now, but it is profound. Pretending that differences and suffering don’t exist is not reassuring. It confirms that we are not available, no matter how many boxes of munchkins we splash out for.

It’s hard to write about differences, facial, racial, or otherwise in September 2020 without writing a sermon (with myself in the front pew).

My daughter was born with bi-coronal craniosynostosis. It is a rare condition that requires skull surgery in the first year of life, surgery which protects the brain but leaves asymmetry in the face. It is sometimes accompanied by syndromes that affect sight, hearing, and breathing. She wore a cute orthotic helmet from the age of eight weeks (thank you brilliant neurosurgeon and committed orthotic expert!) to one year. She has grown into a feisty young lady.

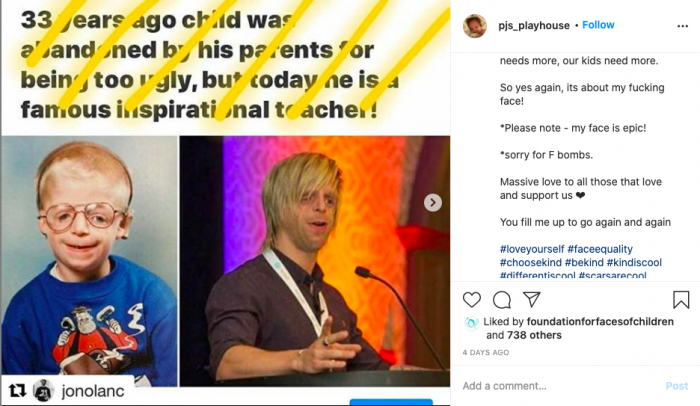

I can’t tell my daughter’s story because it’s unwritten. It’s hers to tell. Will she find mentors and inspiring teachers to uplift her and help her avoid naysayers and stereotypes? Her faith in herself and in life will be seasoned by not fitting in with the norms of appearance.

We assess visually what is a threat, who is an ally, who needs our protection. Even beyond the cruelty of the playground, adults find it hard to know how to act when people look different. One way of responding to visual cues that are complex like racial difference or other physical disparity such as craniofacial difference is to simplify things for ourselves with stereotypes.

I think this arises from impatience, a kind of aggression, which makes us want to know immediately whether someone is worth our time, worth our investment, deserving of respect, confirming our current understandings. Impatience to assume we can know other people within minutes of coming into contact with them is “comfort-zone” thinking.

Does my comfort zone require that I can assess other people’s income levels, their intelligence, their political party?

What happens when I don’t know what’s in front of me when I am on shifting ground? Honestly, we never know what’s in front of us, because “we cannot enter the same river twice.”

If you can become “comfortable with uncertainty”, with “don’t know” mind, yes, it’s weird and scary, but also freeing and beautiful, like my daughter’s approach to life:

“Well, there’s always gonna be people who are going to make fun of you if you’re different, or they’re going to wonder about you. It’s harder than people say just not to pay attention to that. Only people who have had the experience can really know what it’s like, and if someone suggests just ignoring it, you know you can’t talk to them about it; they don’t understand. Our bodies aren’t the most important thing about us, and even if they are, people have so much more to them that we should care about.”

As the saying goes, “In a world in which you can be anything, be kind.”

Ariel Henley, a 26-year-old writer with syndromic craniosynostosis, has a book coming out Winter 2021 from Farrar, Straus, Giroux/Macmillan called A face For Picasso: Coming of Age with Crouzon Syndrome, for anyone who would like to deepen their awareness of this condition.

Read 3 comments and reply