As a clinical psychologist, one of my tasks is to help clients understand feelings that arise as we make our way through daily life.

Living in these unprecedented pandemic times, though, is the first time I am coprocessing with my clients. They continue to awe me with their bravery at facing yet another day of challenges: emotional, physical, educational, familial, financial, and social. Together, we’ve discussed the initial feelings of shock, ambiguous grief and loss, then sadness and isolation, and helplessness, anger, and depression, just to name a few; all of which seem to be riding on a wave of chronic anticipatory fear and anxiety as we mull over our profound existential uncertainty.

It’s a lot. It’s almost too much, at times. And I am moved to tears as I listen to my clients juggle this tremendous time in our lives and in our country’s history. I am honored to bear witness. I am humbled. And I feel a profound sense of connection to them.

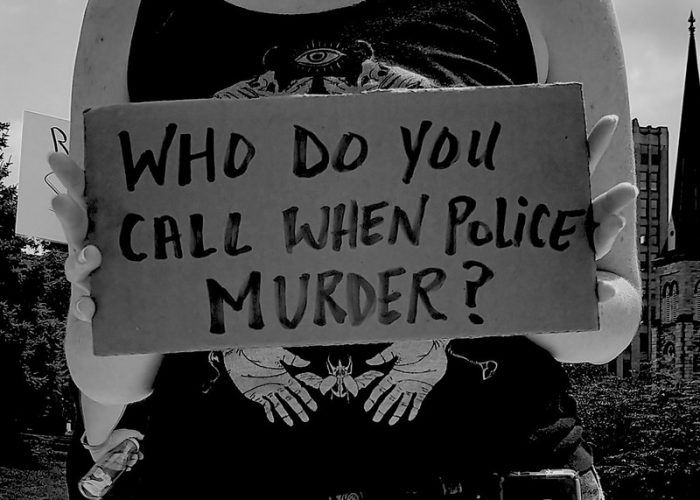

Over the past few months, we’ve all done our best to settle into living with the pandemic, and yet it feels as if these waves of emotions are swelling into an undercurrent of heavy emotions around the faltering state of our country. We are witnessing police brutality, violence, and marginalization of Black people and people of color, the rising death toll of our fellow Americans to COVID-19, the irrefutable global warming and the devastating impact it’s currently having on the people of our West Coast, as they battle five million acres of raging wildfires, and at least 35 have died.

And as if that weren’t enough of a psychological toll, our blood pressure rises with every word spoken from our president and his administration, as we fearfully contemplate the potential loss of our rights and freedoms for which our ancestors have fought unrelentingly hard. No doubt, we are feeling profound weariness and fatigue, as we move beyond our individual pain and hardships to the collective suffering of our communities, society, country, and planet.

What we are feeling is the hijacking of our integrity. We are feeling moral suffering.

In her book Standing at the Edge, Roshi Joan Halifax states that our integrity is made up of:

1. Morals: our personal values, dignity, honor, respect, and care.

2. Ethics: codified principles that guide our society and institutions, and with which we hold accountable.

For example, we consider ourselves to be moral and we value the care and respectful treatment of ourselves and one another. And we want to live in an ethical society where social and governmental institutions uphold human rights and equality, fairness, and justice; and are held accountable when these are broken.

Before I even finished writing that last sentence, I realized, blatantly, that historically and currently we do not live in an ethical society—we see unlawful actions by government leaders, our president, police officers and their departments, and our fellow citizens. This is a chaotic and perilous moment for us, as we collectively suffer the crumbling of our sense of integrity along with our country’s code of ethics, which rests on the democracy and the constitution.

What does our faltering integrity look like?

Roshi Joan Halifax describes three types of suffering:

Moral distress arises when we are aware of problems and a possible solution, yet we’re unable to act because of internal or external barriers.

Our current example of the Black Lives Matters and People of Color Movement is a collective feeling of moral distress.

One of the benefits of social media is the daily campaigning around these issues to raise awareness and action; and it also, justifiably, raises our moral distress. Our integrity may be called into constant questioning if we find ourselves working for organizations that condone racism or sexism, or we may have friends or family members who make comments that undermine the movement for equal justice, and we’ve uncovered the truth of our own racial biases.

Compounded by the fact that our government’s unethical and immoral actions, like perpetuating racism, and refusing to denounce white supremacy, ignoring the majority of our country in calling out for justice and human rights. Moral distress is an “edge state,” where we have fallen over the edge of our integrity of service, leaving us paralyzed and demoralized, feeling helpless and hopeless, if we are not aware of its presence.

Moral distress can devolve into moral injury, Halifax’s second type of moral suffering.

It’s the continuous and conscious engagement or witnessing of morally transgressive acts, such as racism, sexism, human and animal rights violations, or anti-climate change behaviors. These are psychological wounds that abate healing because of the profound guilt and shame that we feel as a result.

For example, many of us have witnessed firsthand brutality and aggression during the BLM protests, and the continuation of justice unserved in victims of excessive and homicidal police force. And, many of our healthcare workers have had to grapple with limited hospital supplies and resources which compromise their patient care, and the lack of government support in adhering to CDC guidelines, as they continue to battle against COVID-19.

And, there are many of our essential workers who are required to consistently confront people not adhering to the mask mandate. We see others, not social distancing, or unnecessarily contributing to global warming through excessive consumerism, plastic waste, and use of fossil fuels, or flat-out denying the existence of climate change.

Whereas moral distress may be more acute or isolated incidences, moral injury is a chronic state of our fallen integrity into an abyss of guilt and shame that is hard to climb out of. We are all a part of the greater societal problem, and we may individually be contributing to immoral acts when the stakes feel so high right now. And I believe that this sustained moral injury will require collective healing when there is a sense of resolution to these current and imminent threats.

And the third type of suffering is moral outrage.

Halifax describes it as a reaction from a place of anger, disgust, and aggression when we witness someone behaving against our code of morality and ethics. We’ve seen this with people’s unwise hostility toward essential workers who enforce a mask mandate, continuous exposure of systemic injustice to victims of police brutality, the unlawful violent attacks on peaceful protestors, the continual and the dangerous disregard of climate, inhumane treatment of immigrants, and cruelty toward animals because we feel like we are part of the problem, individually, socially, and as an American.

And now, our president and many staff persons in his administration have contracted COVID-19, leading to more distress and concern over the health, safety, and security of our government and country. I can easily tap into my moral rage with this president and his administration.

Moral outrage was deeply planted in me after my sister’s murder 13 years ago; and no amount of yoga or meditation will extinguish it. Yet, I commit to these daily practices because they keep my integrity in check, for the most part, and they also hold me accountable when I don’t. For many of us, our outrage and disgust can be expressed through self-righteousness and indignation, shutting down our listeners, creating a stalemate, and ultimately derailing our social cause and acts of service.

Rebecca Solnit refers to this as “recreational bitterness”—when arguing and ego satisfaction become addictive and self-serving, more concerned with proving how “right” we are and “wrong” they are. It takes extraordinary courage to not drop into our moral outrage; instead, hold others and systems accountable, moving toward justice and peace, and less hatred. Joan Didion called it “moral nerve”—the “non-negotiable virtue when standing on the abyss of harm.”

Balancing our integrity from falling over the edge into suffering is much like imagining a continuum with moral sensitivity on the one end—where we are present, aware, and grounded in service, to moral injury on the other end—where we are in a state of despair and helpless and hopelessness, no longer of benefit to ourselves and others.

So, the next time we see someone not wearing a mask, not social distancing, viewing voting as optional, overconsuming plastic and gas, energy not turning off lights or wasting food, to the more egregious human rights violations of racial violence and incarcerated immigrant children, let’s ask ourselves these questions:

What do we want to achieve?

Who do we want to be?

Maintaining a healthy state of integrity means we continue to rise to the call of service by voting, encouraging others to vote, educating ourselves and others around racial justice, donating to BLM causes and human rights organizations, volunteering at social service agencies, especially food banks, and we take very good care of ourselves, and frequently check in on where we are at on that integrity continuum.

And, we practice, practice, practice:

1. Expanding the Circle of Inquiry (S.O.S.; adapted from Joan Halifax’s book, Standing at the Edge)

Self-Awareness: When we find ourselves confronted with a moral issue that threatens our integrity, we get grounded in our body through breath awareness, notice emotions rising, thoughts and beliefs—and ask ourselves with compassion and curiosity:

What is happening right now?

What am I believing?

Other-Awareness: We expand the circle of inquiry to others across from us and increase our capacity to practice perspective-taking, which allows for flexibility of mind and compassion and ask ourselves:

Where are they coming from?

What might they need?

Systems-Awareness: We expand our circle of inquiry to include systems that may be at play here, within ourselves, and between each other. And we ask:

What does it need from me to improve upon it?

2. Establishing vows: the daily practice of opening our hearts, our life to others, and expanding our capacity to serve.

Vows are who we truly are with ourselves and each other and how we choose to meet the world. For example, we can draw from the Buddhist five precepts:

Revere all life

Practice generosity

Practice respect, love, and commitment

Speak truthfully and constructively

Cultivate a clear and sober mind

Like Gandhi’s 241-mile, 24-day Salt March to peacefully protest independence from Britain, to the 1963, 250,00 peaceful protestors at the March on Washington that lead to 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act, to the peak of the BLM marches of 500,000 people across 550 US cities on June 6, 2020, we will continue to march with our hearts, our voices, our hands, and our feet because we are life’s peaceful movement with integrity, and no end.

An excerpt from Cornel West’s graduation speech at Harvard Divinity School (5/31/2019)

“Last but not least, in celebrating you, I want you to never, ever forget that you have the capacity to preserve your revolutionary joy. We live in a culture with a joyless quest for insatiable pleasure. Whole lot of titillation and stimulation possible, but when it comes to that which endures—the deep stuff, the joys that are beneath the pleasures—don’t let anything or anybody take your joy away. I told the undergraduate class at the Black graduation yesterday, I said: Don’t let anybody take your funk away. They want to deodorize you and sanitize you and sterilize you and make you just another example of Harvard graduate and success. No, don’t confuse success with greatness.”

~

Read 23 comments and reply