It was a Sunday evening.

I sat at the kitchen table reciting the Serenity Prayer on repeat as if it was some ancient incantation that had the power to bridge the insanity I felt in my mind and body with peace and serenity that seemed utterly unreachable in that moment. “What is this f*ckery?” I wanted to scream instead.

I had just gotten off the phone with my mother. It did not go well. Once again, the old story of not being seen, heard, or understood played out, and I felt like the jet fuel of rage had been mainlined into my nervous system.

“God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,” I said aloud, my eyes shut in an attempt to calm myself. Another wave of rage crashed through me as I swayed in my chair, praying to all hell for this emotional tsunami to pass through.

Stay with it, said the internal voice.

I am! I thought. I’m staying with the f*cking feeling!

“The courage to change the things I can.” The next verse of the prayer unspooled.

Four months ago, I had started a 12-step recovery program, and right now, the damn prayer is all I could remember.

The rage and hate that flooded my body were akin to Katrina pushing against the sandbag levees that offered no guarantee of holding back the intensity of my emotional storm.

Breathe, said the voice. I started to rock back and forth, like the Jewish do when they engage with the Torah. “And the wisdom to know the difference,” I said out loud…and again.

“I hate you!” I shouted at nobody. “I hate you!” I screamed at the night sky beyond my living room windows. I wrapped my arms across my chest and hugged all those inner children who were raging. It felt like an army inside. F*ck! F*ck! F*ck! This hurts!

As a child, I learned that staying quiet in reaction to loud, domestic arguments would keep me safe. I’d curl up into the tightest ball possible in an attempt to protect myself from the rage monster that lived between my parents. I’d often pray to my guardian angel to make Mom be quiet so that Dad wouldn’t be so angry with her for saying things he didn’t like. I took seriously the task of being a good girl under all circumstances as not to provoke anger in my parents.

As an adult, sifting through these traumas as part of my recovery from codependency, I look back and imagine that my dad felt trapped. He and Mom got married because she was pregnant. It’s how things were handled back then. I never knew what dreams were thwarted by my arrival. He drank excessively and the rage showed up after his visits to the pub. Alcohol meant anger and anger meant violence.

Mom, I imagine, felt powerless about being a mother at 17 while married to a man who she could not trust to treat her with decency and respect. From her, I learned the value of hypervigilance. I became adept at noticing the pulsing of the tiny muscle in her jaw when she clenched and unclenched her teeth, took note of how much force she used to shut the kitchen cupboards and drawers, honed my hearing for loud sighs along with the rubbing of temples—all those were signals to make myself invisible.

I get it! The 54-year-old me gets it, but the inner children living inside me revolt each time I repeat my childhood programming and push down my feelings of anger.

Until this night, when the courage to feel it all found me and would not let go.

I continued to sit at the kitchen table holding space for my inner brood of children, the way I had wanted my mom to hold space for me during our telephone conversation. I wish I could write that I walked away calm, cleansed, and free of the sticky anger, but that is not what happened.

For the next six days, the echo of that rage showed up in my body as a burning sensation between my shoulder blades, shooting pains down my left leg, and a constricted diaphragm, all wrapped up in lethargy.

I know that unprocessed emotions leave an imprint in my body. This is no news to me, and yet, I resisted letting this one go. I actually appreciated the anger energy. It’s something I had never given myself permission to stay with because in my past, anger led to violence and that terrified me.

I negotiated with the Universe to let me hold on to the anger a little while longer. I wanted to be unreasonable; to let myself feel the unfairness of it all, to lick my childhood wounds within the safety of my rage. I wanted to take the low road, just this once; to have a temper tantrum, stick my tongue out the way I wasn’t allowed as a child, to kick the bedroom door, throw toys across the room, to jump up and down, and roar like a rabid animal.

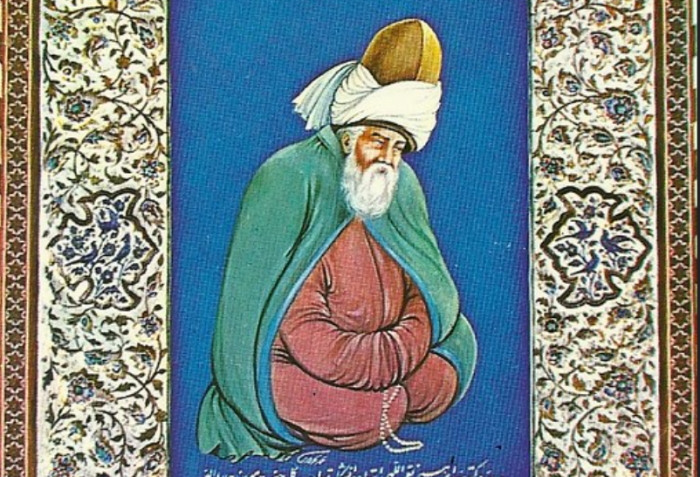

I stayed with the anger, self-righteousness, and indignation for five days and on the sixth morning, I began to sense a softening in my solar plexus. Tears came; sadness came; sorrow came; acceptance came—all the makings of grief made an appearance as I sat in meditation. I hugged the little ones inside me and remembered Rumi’s poem, The Guest House:

This being human is a guest house.

Every morning a new arrival.

A joy, a depression, a meanness,

some momentary awareness comes

As an unexpected visitor.

Welcome and entertain them all!

Even if they’re a crowd of sorrows,

who violently sweep your house

empty of its furniture,

still treat each guest honorably.

He may be clearing you out

for some new delight.

The dark thought, the shame, the malice,

meet them at the door laughing and invite them in.

Be grateful for whoever comes,

because each has been sent

as a guide from beyond.

Rumi writes of surrender, of allowing all that arises within us—whether light or shadow—to be given the same treatment of gratitude. The anger I had finally let myself feel at my mother was the explosion necessary to take care of my need to be seen, heard, and understood. Anger was the catalyst. It cleared the way to practice selfishness in the noblest of ways—by paying homage to my emotions as if they were guests sent to guide me.

When we find the courage to stay with our uncomfortable emotions, we are parenting ourselves in the most loving and accepting way imaginable. To be able to say: Yes, I feel hatred and I still love me. Yes, I feel angry and that’s okay, is practicing self-acceptance. We are listening to ourselves, seeing ourselves, and understanding ourselves in our totality. It is from this place that we begin to glimpse the peace and serenity that only self-love can bring.

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 37 comments and reply