View this post on Instagram

I heard audible gasps around me as I glanced at myself in the mirror.

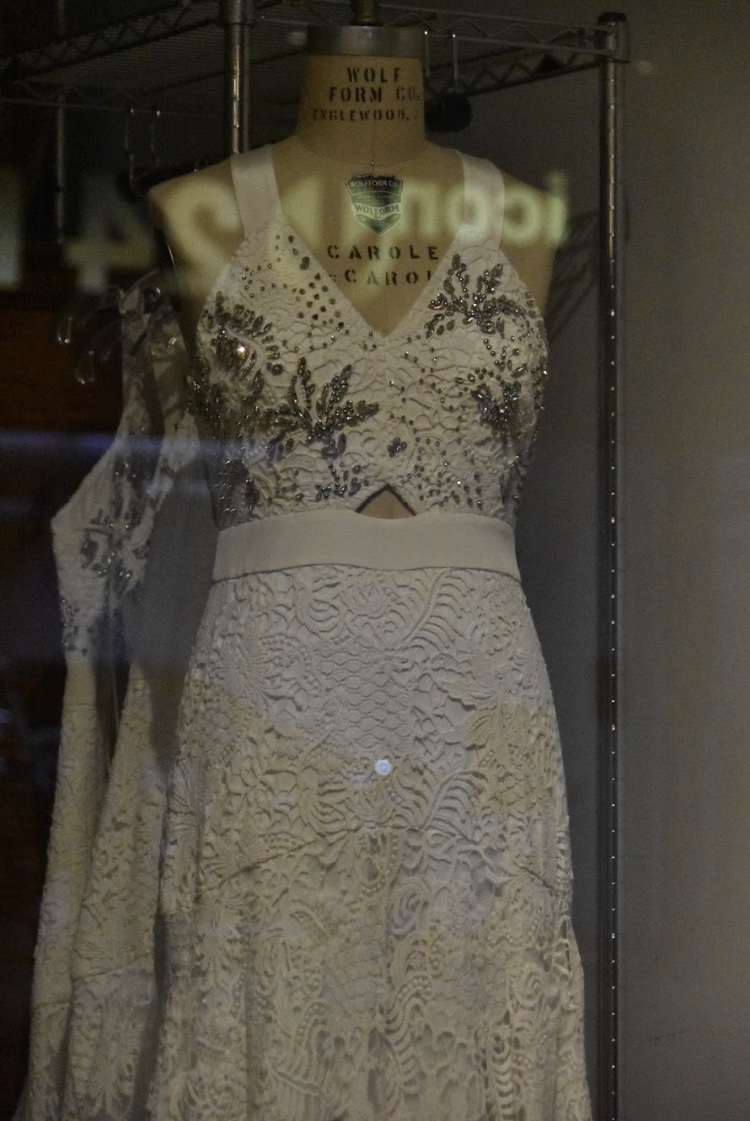

My eyes softened, and I held my own inhale until I could no longer bear the expansion in my chest. As I stepped from the dressing room of the vintage dress shop, the one of a kind lace and silk of the 1930s wedding gown cascaded around my body.

I followed the warm tingling of excitement in my skin, trusting that the occasion to wear this garment would inevitably follow, as it had with every other garment purchased at the same shop, in the same way.

From all the apparel acquired during that era of my life, it alone remains unworn.

Years later, wrinkles now apparent on my face, I was suddenly and commonly asked in retail shops, “Where is your husband?”

Strangers frequently asked me to explain why I had not been married or what happened in my life that had brought me to this unsavoury spot “at my age.” They sought answers in one singular simplified question, hoping to learn what was “wrong with me” for not upholding their normative expectations.

These questions unravelled me as I unexpectedly slammed into a wall of shame.

I remember staring at the floor-to-ceiling black silk curtains of my living room, the thickness of the fabric matching the texture suffocatingly lining my lungs. The wintry frost covering the windows bleakly transmuted to my heart as I coldly realized: I had failed to do what culture instructed me to do.

This is not an active choice of rebellion but instead a simple lack of ever doing it, yet I deemed myself unchosen and unworthy.

I wondered where I had failed. Dating narratives had trained me that love and subsequent commitment would happen when I would “least expect it” and that if I simply “live a life I love,” a man would notice the magnetism of my life, be drawn in, and eventually propose.

No person I knew lived out more of their passions than I did and no proposal had ever come. What had I done wrong?

In my head, to not be chosen equated to a tattoo reading, “no man must want her.” I was sure others were wondering in hushed tones if singlehood was my choice or if I was either too picky or too demanding. I wondered what they had concluded.

As winter passed, I picked myself apart: I was overcome with imaginary regret for what I did not know earlier in my life, obsessed with what decisions might have changed this bleak scenario, and filled with a fantasy about how a husband would now heroically save me from these feelings.

I hoped that the silence of solitude would combat the shouting in my head, and I withdrew from other people lest I infect them too.

Angrily, I removed the wedding dress from the hanger in my closet and stuck it in a paper bag on the floor so that I no longer had to see it.

What we fear most about shame is the darkness. We push the black feelings further inside to try to make them less visible to others, obscuring the truths we least want noticed into the deepest corner we can find.

Without my permission, my shame was visible: I wore no ring, and my marital status resided directly under name and birthdate on seemingly every form ever created. With no way to hide, I had to dismantle it.

Verbalizing our shame sheds a light into the dark crevices, diffusing the power of the imaginary ghosts screaming from within our hearts.

I started announcing my marital status with direct eye contact and confidence in my voice rather than looking away and muttering, “I don’t have a husband,” making the inquirer often more uncomfortable than I.

I diverted questions about my “divorce” by updating my dating profile, making it clear that I had no situation from which to divorce. I was surprised to learn that these inquiries were nothing more than idle small talk—when I volunteered the information, it ceased to be a conversation point.

At the core of shame is a fear of disconnection. We fear we won’t be accepted by others, believe that we are alone in our discomforts, and fear that we have nothing to offer.

I cultivated connections with other unmarried women, volunteering with an organization that worked with young moms—an endlessly rewarding role. It helped reinforce that others were in my situation, that we shared a common humanity, and that I had plenty to give.

We are afraid that which we are most ashamed of makes up the majority of our personhood, rather than a portion thereof.

I “perspectivized” my marital status, once dramatically escalated as my whole identity during a single moment of internal shame-flooding, now softening and representing itself as a mere fragment of who I am.

Shame is an inside job.

I started offering myself the same softer tones of loving-kindness that I would give to another during an emotionally difficult time. I would catch myself endlessly assessing, analyzing, critiquing, and doing the effortful work to change the tone of my response to myself.

We can always find validation of our flaws if we seek it out. Instead, if we can find compassion for ourselves by re-narrating the voice in our head; we can say to ourselves that which we most need to hear:

We are not alone.

We are not being rejected.

This is not the whole of us.

We can be as kind to ourselves as we would be to others.

As the year passed, the voices of the invisible ghosts shouted less loudly, becoming first a whisper and then a quiet hum.

On a white beach in Barbados, I blew out the candles on a red velvet birthday cake acquired to commemorate the occasion, and with it, a lightning bolt of awareness: my shame was extinguished along with the candles in a moment of celebratory awareness that the heaviness had passed.

The voices of cultural expectation were gone, and instead, I saw my marital status as something interesting and unique.

Author’s own

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 35 comments and reply