The oldest continuing human experiments regarding affect, or how things feel, have been recorded for us in the annals of religious confession.

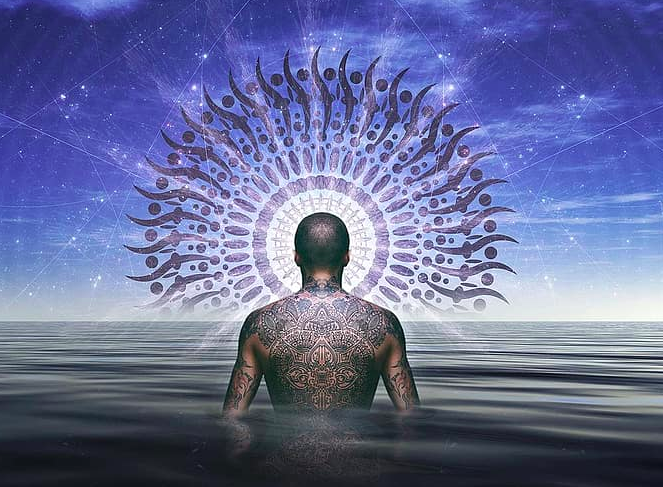

For that is what religions do: they cultivate feelings. Whether by the sudden uplift of one’s attention and spirit achieved within a Gothic church or by the unity of cosmos and self-experienced during the beating of a Sun Dance drum, religions exist to cultivate particular affects, which themselves are organized to bring the feelings of healing, orientation, and fulfillment.

Conceived this way, spirituality can be understood as the original forum for therapy before scientific psychology existed. When I first thought to explore this idea, I never expected to find profound, radical, and even subversive therapeutic theories and practices among the great religions. My book, Making Peace with the Universe describes the harrowing personal backstories of some classic works of spirituality in order to understand how therapeutics once operated, and also to see if these might still contribute to personal well-being today.

To be sure, there have existed a wide range of spiritual affects and feelings. Yet most have shared in their articulation of one feeling in particular: gravitas. By this, I mean something like spiritual weight. The world often feels as though it has weight. People are born and die; things are created and destroyed; the world evolves and devolves, and typically, these changes feel as though they matter. When one does slip into a mood of believing that nothing really matters, even that view can come with its own feeling of gravitas, an unbearable lightness of being.

Somewhere along the way, the geniuses whose spiritual crises I explore came to realize that recognizing and facing their personal feelings of spiritual gravity was an essential element in learning to live with themselves. They began taking such feelings seriously and exploring them. Like many others, these hurting people found themselves pulled toward spirituality, the forum in which so many had been considering the weight of the world for so long, and the place where people tried to align their own actions with this gravity.

Why did they all bother? What was the point? They discovered that, for them, turning toward gravitas felt orienting, integrating, and grounding—as opposed to disorienting, scattering, “lite,” and empty. That is to say, turning toward gravitas felt therapeutic. It felt healing. It felt edifying. It felt good in the weighty sense of the word. They report becoming suddenly clear-minded and justified when finally abiding by this suprarational orientation, often when reason warned that they were just being naive. If I may suggest, the gravitas affect is the higher power articulated by these spiritual masterpieces, the mysterious inwardly felt tug to return to one’s own right way, despite all sirens.

Noticing gravitas (spiritual weight), and orienting oneself to it, achieved for these masters the affect that William James called, “enthusiastic assent” and “a mood of welcome.” The mechanism for coming to this state rested precisely in directing attention to some larger concern when one’s private energies (whether conceived of psychoanalytically as id, cognitively as the Jamesian emotions, or neurologically as the limbic system) had become problematically self-obsessive, even self-destructively so.

Put another way, the pains and frustrations of the private appetites became tempered by contextualization beyond themselves.

The means of spiritual therapy then had two levers:

>> One felt the weight of the world. One experienced gravitas, an unseen but discernible orientation toward some larger concern beyond the private appetites—a higher power, as it were.

>> One discovered a therapy of commitment. One found that personal welfare could best be addressed by giving oneself to this gravity.

Across diverse cultures and irrespective of historical moments, geniuses I describe such as Socrates, Muslim legal scholar turned mystic, Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali, Mongol emperor, Genghis Khan, and jazz composer, Mary Lou Williams, each did this. Each discovered his or her own common cause with a looming universe. This seems to me to be the very means of spiritual therapy as it has been practiced classically for millennia: noticing the weight of the world and giving into gravity.

In so doing, each one managed to change the quality of emotion from that of grudging consent to worldly circumstances, and found a position of “enthusiastic assent” to those very same circumstances. For those of us with similar spiritual curiosities, we too may come to make peace with the universe and also with ourselves.

~

Adapted from Making Peace with the Universe: Personal Crisis and Spiritual Healing by Michael Scott Alexander, © 2020 Columbia University Press. Used by permission.

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply