Author’s note: all details in this story—including names, ages, genders, and other specifics—have been changed to protect everyone except me, the author.

~

Sometimes, the reality of it all still eludes me, although it is less frequently so.

For one brief moment, I may wake up in the morning, stretch, and think about coffee, a run, and my dog—and then BAM! I remember there is COVID-19, and homeschooling, and the mask fighting, and on and on and on.

Still, I force myself out of bed (it is getting harder to do this lately), and I put on running clothes and get 45 minutes of mental clarity before donning one pair of nine scrubs that I own.

I head in to work, after scratching out a little note encouraging my sons to actually do some homework today instead of watching more TikTok. I include an afterthought, asking them to make their beds and do the dishes, then I rush off to work. I wonder if they will see my note.

Parking is not a problem these days. Our COVID-19 patients cannot have guests, and half of our hospital administrative staff now work from home, so whereas I used to have to hustle a spot a year ago, today I can literally park across the street and run in the front door.

I take my temperature with a thermometer that registers low every day, so I wonder if it is really helpful or if I am still cold from my Minnesota morning run. I answer all of my questions while I raise my eyebrow.

1. Have I been exposed to someone with COVID-19? (Only the 16 or so patients for whom I cared the day prior, half of whom coughed respiratory viral droplets all over me. But I was wearing my PPE.)

2. Is anyone I know sick with COVID-19? (Define “know.” Maybe. I mean, I know a lot of people, but I also know to stay away from them. However, my 16-year-old son is a variable, and I am not sure he cares, in spite of my lectures and pleas, so have I really stayed away from someone with COVID-19?)

3. Am I exhibiting any symptoms of COVID-19? (I don’t think so. I still taste, smell, and I don’t have shortness of breath or cough. I don’t think I have fevers, but I had a good menopausal hot flash that awoke me last night and saturated my sheets. I ache a little bit, but I fell on some ice the last time I ran. I opt for the answer “no” as in “no symptoms.”)

And, with that, I am off to the races.

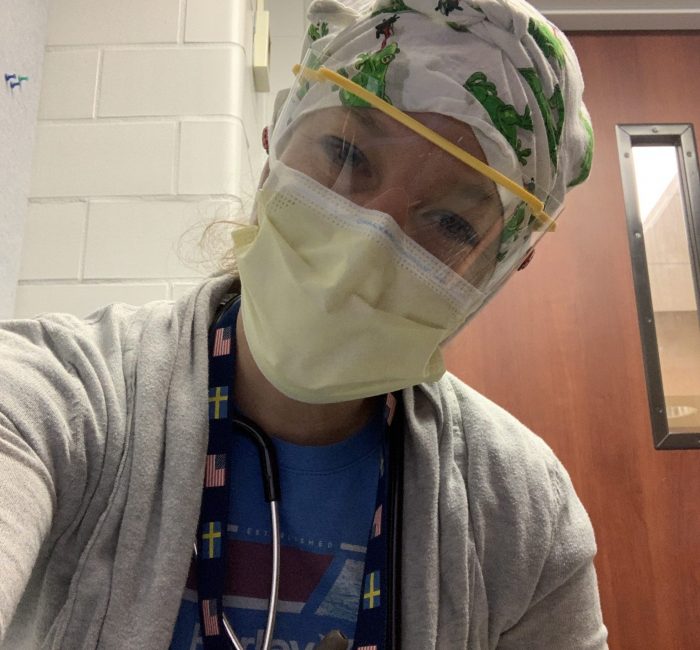

I avoid my shared desk on the 10th floor because it is excessively close to another doctor, less than two feet, a sweet friend of mine with a few small boys. I wouldn’t want to get him sick, just in case I am mysteriously carrying around the virus. I gather an N95, some goggles I had from yesterday, an extra surgical mask, and my plastic shield, which waits for me on the plastic shield tree at the nurses’ station. I print my list and I see that I have 15 patients today, a mercifully do-able number. I see the usual suspects and some new people, and I also notice that all but one is positive for COVID-19. I actually miss the days of caring for someone who has overdosed on heroin, and I wonder where all of those patients are.

I stop and greet the HUC (health unit coordinator) who happens to be a woman from my hometown. The charge nurse alerts me to some abnormal labs, and then mentions that Mrs. Johnson is requiring much more oxygen this morning, and maybe I should see her first. I glance at the list and notice that there are two other new ones in the ICU, so I decide to see Mrs. Johnson first and head to the ICU after.

Mrs. Johnson is a sweet, widowed lady, about 70 years old, who thinks she contracted COVID-19 from her daughter. She is a former smoker, but otherwise has a relatively small list of medical problems and a life outside of the hospital that includes a beloved dog, her daughter who works in a school, and a son who she doesn’t talk quite as much about. Yesterday, we talked a little bit about a ventilator, and she assured me that yes, she would want to be on one, should she worsen. In her words, she didn’t want to die yet, and she would like to see her children, who are in their early 30s, grow a little older.

I knock on her door this morning, after donning all of my proper PPE and foaming myself silly. Mrs. Johnson has changed overnight. This morning, her lips, chin, and fingertips are blue, her oxygen levels are dangerously low, and she’s on maximum heated high-flow oxygen therapy through white tubing and large plastic prongs, one in each nostril. She’s working hard to breathe, so I place my index finger up to my mouth area, the hush symbol, signifying that she need not try to speak if she’s not able.

“Hi, Mrs. Johnson,” I say. “Looks like it was a tough night.” I assess her breathing rate, and I ascertain that it is somewhere over 30 breaths a minute. I don’t think I can bridge her to stability with a forced air mask, and I think she is going to need that ventilator. “I am so sorry to have to tell you that I think we are going to need to have you rest on the ventilator, to give your lungs some more time to heal from this virus,” I tell her.

I hold her hand, and I assure her that she will receive excellent care. I tell her that we are not giving up on her, and she still may have a chance to survive this, although I know that her chances just became exceedingly smaller. I put my arm around her back, hoping this isn’t the final hug she will receive on this earth, and I hold my breath when I do so, because even though I am feeling compassion for Mrs. Johnson, I am scared for myself when I get too close to someone who is infected. I tell her that I will call her family, both of her children, and tell them that she loves them and she is continuing to try to get better. Out of the corner of my eye, I see her oxygen saturation is now less than 70 percent, and I know I must hurry.

I exit the room, doffing the PPE, somewhat excessively foaming my hands and my earlobes (they touched the stethoscope in the room), and I wipe my shield. I call for anesthesia STAT for intubation and then transfer to the intensive care, which takes two extra hours because beds are full and we’ve had to shuffle patients around.

When that is all accomplished, I finally sit down to call the family.

By then, I am fatigued and a little emotional. I feel as though I’ve run a race, and I worry that the deterioration of Mrs. Johnson might reflect something in my care, or lack thereof. I take a deep breath, because I learned that this helps to deactivate my sympathetic nervous system, which gets triggered any time I participate in a medical emergency. I dial her daughter first, and I am met with an exceptionally grateful, kind young woman who is afraid to lose her mom. She weeps as she speaks to me and asks how she can be updated throughout the day. I lamely end the conversation with a meager, “I am so sorry for your mom.” I also call her brother, and he says much less. I feel as though I’ve let them down, somehow, because I cannot fully understand how and why this virus works the way it does. Also, I have no guess as to how Mrs. Johnson will do—I can only state that she is critically ill and will now be cared for by our intensivists (I am an internist), and that they are very good at taking care of the very sick.

I finish my rounding and my notes and my day in the hospital, and I check on Mrs. Johnson before I leave, except she is now proned (in a kind of skydive position on her belly) in an isolation room in our intensive care. She is sedated, she cannot have visitors, and her nurse is busy with another COVID-19 patient, so I quietly leave the hospital.

At home, I throw the scrubs straight into the wash and I hop in the basement shower. I scrub and scrub and scrub my body free of likely one layer of skin, and maybe some microscopic virus that may have found its way onto my body today. My boys are at hockey, which is good for them, but a wonder considering school cannot be held in person. I dress quickly, then hurry to the gas station to make it to my oil change appointment. Because of the pandemic, I am overdue for this.

Two guys greet me and get to work on my car. I head into the building where there is a small waiting space. There is a woman there, with a child, and both are sitting quietly wearing masks, but there is not six feet between them and me, so I move on. Within the store, there is a back hallway where I can watch the driverless cars roll through the touch-free wash and try to escape live humans. Numbly, mindlessly, I watch the cars roll by, lost in the bliss of no thoughts—something I have little luxury of during my day.

I smell her before I see her.

I catch a distinct smell of a sweet vape, and then I see the smoke in the hallway. She looks tough—likely, she is about my age but has lived a harder life. No mask, lots of smudgy mascara, and typing fervently on her phone while holding her JUUL. She is pacing the hallway without regard for anyone else, and she passes right behind me. I hold my breath, exiting the hall quickly. I glance back again, and she is pursing her lips, blowing her vape smoke straight into the hallway toward another customer further down the hall. I head straight toward the clerk.

“Hi,” I say. “I wonder if you could enforce your mask policy?” He looks at me with dread. I explain that there is a woman in his back hall who is vaping and not wearing a mask, and I ask if he would encourage her to do so. He takes a disposable mask with him and he asks her to please wear it. She states that she “forgot hers in her car” and she puts the mask on. I feel a little relief, and I hope the message will stick with this woman in the future.

My car is almost done, and I really want to get home. I can almost feel my couch, and I think about whether I will drink tea, seltzer water, or whether I will splurge on a porter. I lean back and close my eyes, waiting.

About three minutes later, I again smell the vape, and I can hardly believe it. I look to my right, and there she is, wearing her mask around her chin and blowing her vape toward where I am sitting. I can’t stand the arrogance, the selfishness, and the flagrant disregard for others that she is exhibiting in a public space. I remember Mrs. Johnson, and any residual patience and discretion leaves my body.

“Excuse me.” I stand six feet away from this woman, and I am clearly talking to her. “Yes, you. Wear your mask. And stop vaping on all of us,” I say, with obvious annoyance in my voice.

She looks at me with blatant hatred, and she says, “It is my right. This is my freedom.”

“No,” I answer. “This is about everyone else’s right to health. Do you want to infect other people? Do you want to spread a real, deadly virus? Are you that selfish?”

She unleashes. “I’m so sick of you people. I’ve had enough. Stay home if you are so scared of the virus.” She is pulling at her mask and sits back, folding her legs and arms in a stubborn defiance.

My voice is loud now, and I am sure the entire store hears me. I really don’t care.

I am tired. I am physically tired of COVID-19. I am mentally tired of COVID-19. I am emotionally tired of COVID-19. Just like everyone else.

But I see what is going on from the inside. I see the suffering, the pain, the isolation. I am one of the last people some people see before they are put on a ventilator and later die of the virus. I hold hands, give PPE protected hugs, and I tell families that their loved one’s last words were that they love them. I hear their words when they tell me that they do not want to die, that they now understand how deadly this virus is, and they wish that they had been more careful.

They are scared, they are sick, and they are suffering.

And this woman cannot wear a mask. She cannot stop vaping.

“Do you know what I did today?” I start. I take a breath inside my mask, then I lean in. “I cared for a woman not much older than you.” My finger points at her, a gesture often mocked by my children when I am disciplining them. I go on, “She has a family. She lives in our city. She might have even used this car garage.”

“She got COVID-19, maybe because of someone like you. The virus is winning, despite every option available to her, and I’ve tried everything. So I put her on a ventilator today, just about seven hours ago. She might die. Maybe even tonight. And yet you want to sit here, blow your smoke at me, and talk about your freedom to walk around without your mask? You could be spreading the virus, and you don’t care! Look up the data—masks work. It is a scientific fact, or all of us who care about science wouldn’t be asking all of you others to please, please wear one. For God’s sake, start taking this seriously. Do your part. Because you know what…you might be my next patient. And you know what else? I will still take care of you, even if you are sick. So the very least you could do is have enough respect in the meantime to help take care of me, and all of the rest of us.” I gesture to the three others watching me. They are each wearing masks, but I know their mouths are hanging agape underneath.

I become aware that I need to leave. I honestly didn’t meant to lose it, but the vaping has unhinged me. I see that my car is ready, and I leave. I go home and I drink that porter. And I listen to some jazz music, talk to my friends, pet my dog. And I help with homework—algebra, to be specific.

I breathe deeply.

And finally, I meditate and pray for an end to this nightmare. Then, I go to bed.

I awake the next morning, forgetting for one blissful second that the world is in the middle of a dehumanizing, divisive, and horrific pandemic.

Read 15 comments and reply