Warning: Spoilers below about Pixar’s “Soul!”

~

There are probably people I met in my 30s who, if asked what they remembered about me, would say, “She was passionate about yoga.”

They might not know or remember much else. Not my love of science fiction books, or that one of my favorite movies is “Bloodsport,” (Jean-Claude van Damme, sigh) or that once in a while, I crave (and eat) a bag of crunchy Cheetos.

They wouldn’t know any of these things because I probably wouldn’t have mentioned them. Instead, I would’ve talked nonstop about yoga—for yoga, I believed, was my purpose.

I don’t remember much about the personal preferences of the people I met back then, either. If we weren’t talking about or practicing yoga, or if the topic didn’t get somewhere in the proximity of finding our purposes, I didn’t invest much energy in learning or remembering the minutia of someone’s day or personality quirks.

I cringe, admitting these things. And I hope it’s not as bad as I’m telling it, that I’m being hard on myself, and that people do remember more about me than just my Downward Facing Dog.

But it’s the undeniable truth that for about a decade, I was so single-mindedly focused on teaching yoga and spirituality that I couldn’t see or hear much else. It wasn’t just a mere hobby or interest. Yoga was my purpose, what I was here on this planet to do. Nothing else, certainly not growing personal relationships that didn’t revolve around our mutual love of yoga, felt particularly relevant to me.

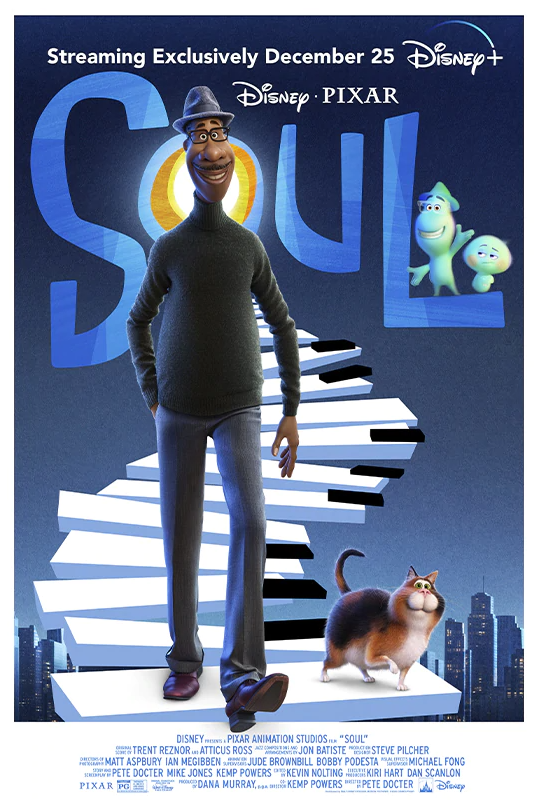

When I met Joe, the main character in Disney Pixar’s “Soul,” these memories from my 30s washed over me. I felt both compassion and pity for this younger iteration of myself.

In “Soul,” no one who meets Joe doesn’t know that his life purpose is jazz. In fact, it’s all he talks about. In his mind, jazz is his reason for living. The problem is, even with his talent, he is “stuck” in the role of a middle school band teacher. Because this role doesn’t match up to his idea of a fulfilling purpose, he feels incomplete, unsatisfied, inadequate.

I remember saying and believing similar things about myself when my yoga business ended abruptly in 2010, and my one chance (as I saw it) to fulfill my life’s purpose vanished.

For years, I had been building up my sense of value and worth through my work as a yoga teacher. Without that work, without my purpose, who was I, anyway? Just some human being taking up space?

It would be a long time before I would learn that my inflated sense of self was only an illusion, and that true self-worth could only arise from examining and accepting all facets of myself, not just the one in which I played the role of a yoga teacher.

Joe feels similarly let down by his lot in life, and deeply disappointed with himself. He doesn’t see the gifts he’s using and offering every single day. He’s squandering his life away while pining for a purpose.

Suddenly, just as he’s about to get his Big Break, Joe has an accident. He voyages not to the Great Beyond, where souls go after death, but to the Great Before, where souls reside before they are born.

In the Great Before, Joe, in soul form, meets a soul named 22, who has stubbornly refused to take on a human body again. She believes the whole thing to be a colossal waste of time. In this, she spotlights Joe’s inner negativity. Joe is assigned to mentor 22, but instead, Joe uses this opportunity to finagle a way back to his body, his life, and to his Big Break.

But something gets mixed up on the way to Earth, and, like a soul version of “Freaky Friday,” 22 enters Joe’s body, and Joe enters the body of a cat.

And so the adventure begins.

For 22, it’s the adventure of being in a human body—smelling, tasting, and feeling things again.

For Joe, it’s about taking on the uncomfortable role of observer of his own life (or what we would call his “witness consciousness” in the spiritual world).

People who might’ve played superfluous roles to his purpose suddenly become extraordinary teachers and mentors. For example, his barber.

He discovers that his barber did not originally intend to become a barber. It wasn’t his purpose. He had hoped to be a veterinarian until life guided him in a different direction. Joe jumps to the conclusion, based on his own perceptions about “purpose,” that this is a sad story and his barber is now “stuck and unhappy.”

But his barber quickly corrects him: “I’m happy as a clam, my man!”

During his hair appointment, Joe realizes, with a wash of shame, he’s learned nothing about this man who’s been cutting his hair for years. All they’ve ever talked about is jazz. Oh, did I relate.

Joe, in cat form, watches 22, in Joe’s body, engage in and immensely enjoy the minutia of life, things such as lollipops, pizza, and getting yelled at on a train.

22, waking up to the beauty of human life, exclaims to Joe, “Then you showed me about purpose and passion, and maybe sky watching can be my spark, or walking! I’m really good at walking!”

But Joe quickly corrects her developing (yet correct) assumption about purposes: “Those aren’t purposes 22, that’s just regular old living.”

Joe, as stubborn as I was, takes a while longer to learn his lesson.

Ever since I was a child, I can remember feeling the need to prove my worth through my actions in the world. Just being myself, just staying present, was never enough.

So I related to 22 when she admitted, “Truth is, I’ve always worried that maybe there’s something wrong with me, you know? Maybe I’m not good enough for living.”

I became wholly obsessed with finding my purpose when immersed in the New Age world. I soon believed that all souls come to Earth with a specific purpose and that it was our job to find it and claim it. I believed that a failure to do so or to take too long to do so would be catastrophic. This all translated into a belief that everything I did unrelated to finding my purpose was a waste of time.

I know now that I talked about yoga back then, rather than about more personal things, to cover up my sense of inadequacy. I was on a mission to prove my worthiness. I needed to show the world that it needed me. All that neediness drove me to block everything else out.

Ten years and a lot of spiritual guidance later, I have completely dropped the whole idea of a life purpose. Instead, I simply follow my curiosity, wherever it leads, and whatever it might be about—from the minutia of daily life to the mysteries of the cosmos.

So I laughed aloud when in “Soul,” one of the mentors from the Great Before remarks, “We don’t assign purposes. Where did you get that idea?”

Where indeed.

We can probably all name or find hundreds of books, seminars, and teachers who talk, perhaps in their own branded way, of finding not only meaning through purpose, but joy, satisfaction, and even belonging. In fact, we can find dozens of articles, right here at Elephant Journal, promoting this idea as well. (And here, and here, too.)

But to blame the New Age world isn’t really fair. After all, it didn’t just pull these ideas out of a void. They were adapted from our mainstream culture, and all the stories and lessons that portray a protagonist who overcomes all the odds to find their “one true gift” and lives happily ever after.

Especially in America, where we have a strong belief in the hero archetype, we know that a hero cannot be a hero until they have found their purpose.

Through popular culture, as well as our upbringing and education, we learn in both overt and subtle ways that humans must earn the right to take up space: You need goals; take this test and figure out what you’re supposed to be; no, don’t take those classes they won’t further your ambitions; you have to do something with your life; make something of yourself; be worthy; make us proud.

We believe, whether knowingly or unconsciously, that finding our purpose will mark the true beginning of our lives. Our purpose must be nameable and understandable and it must contribute to the world in an obvious, direct way. None of this “good listener” B.S.

This powerful belief in purpose and the tangential beliefs that sprout from it constantly shape how we feel about ourselves, how we spend our time, and what we value.

This is illustrated perfectly when Joe (through 22, it can get a bit confusing!) admits to his mother that he’s “afraid that if [he] died today, then [his] life would’ve amounted to nothing.”

Can you imagine this pain? Maybe you can. I know I can.

Meanwhile, we find 22, a soul who couldn’t even find a spark in the Great Before, eating pizza, star watching, and walking, all the while amazed, curious, and living each moment to the fullest.

Joe eventually does get his Big Break chance. Finally, finally, he believes he’s landed in his purpose! And for those of us raised on the steady diet of purpose culture, we are likewise prepared for this moment to be his happy ending.

He relishes in the moment, and we do, too. It is a beautiful moment.

But when it’s over, and “normal” life returns, he looks dumbfounded. He asks the woman who gave him the opportunity, “What do we do next?”

“We come back tomorrow night and do it all again,” she replies simply.

Joe reflects, “I’ve been waiting on this day for, my entire life…I thought I’d feel different.”

She then tells him a story.

There was a fish swimming in the ocean. He swims up to an older fish and says, “I’m trying to find this thing they call the ocean.”

“The ocean?” says the older fish. “That’s what you’re in right now.”

“This?” says the younger fish. “This isn’t the ocean. This is water.”

It is then that, finally, Joe looks back on his life and sees all the little joys and special moments. Things that he’d not seen or appreciated before. He even realizes that he loves teaching middle school band.

Over the course of the movie, Joe reassesses the whole idea of the “meaning of life,” something that, at the end of 2020, seems particularly important that we all do.

Every teaching—no matter if it is taught in our shared society generally or in the New Age world specifically—comes with both light and shadow.

The light of the purpose teaching: the idea that we all came here with a purpose can give us focus and drive in our lives. It can inspire us to search deeply within ourselves for our deepest passions, beliefs, and motivations. It can keep our eyes open, our curiosity sparked, our energy youthful.

The shadow: we can easily get stuck believing that nothing else matters but our purpose, and until we find our purpose. In the Great Before, we meet “lost souls” who are described as people who “can’t let go of their own anxieties and obsessions, leaving them lost and disconnected from life.”

If we aren’t mindful of the power of this belief in purpose, we too can become lost souls, disconnected from life, engaged only in the activities and interactions we believe will further our purpose while missing everything else.

As someone says in the Great Before, “Oh, you mentors and your passions. Your purposes. Your meanings of life! So basic.”

It might not be easy for us to move from a belief in purpose to a belief that there is no purpose other than to feel and be human, as 22 shows us. It’s difficult to unlearn ideas that are so deeply instilled in us. The ego doesn’t easily give up these kinds of things. But, we can trick it: Rather than letting go of the belief in purpose, we can state our purpose in terms such as these: To grow, to evolve, and to expand our understanding of ourselves through experiences that can only be had in a human body.

Whether this happens for us through taking one particular view on life or dozens, whether we try out one way of living or a million and one, gold (happiness, joy, meaning) can be mined from wherever and whenever we are paying attention.

If that’s not yoga, I don’t know what is.

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 23 comments and reply