If you’re lucky enough to have someone in your life who exemplifies the best of human qualities and shines with spiritual depth without trying to, I urge you to cherish that person while you can—and remain grateful for them when they’re gone.

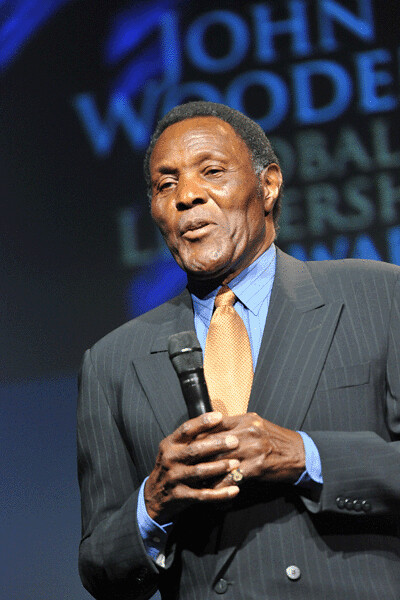

I was blessed to have such a great soul as a friend and collaborator. When Rafer Johnson passed away on Wednesday, he was properly celebrated in the press as one of the 20th century’s greatest athletes, a precedent-shattering public figure, a civil rights activist, the stalwart who wrestled the gun from Bobby Kennedy’s assassin, the majestic lighter of the 1984 Olympic flame, and an all-around admirable human being. If you’re too young to remember Rafer, Google will fill you in. Meanwhile, here is my personal homage.

I first met Rafer Johnson in 1995, over lunch in Santa Monica. My agent, Lynn Franklin, had arranged the meeting because Rafer was looking for a writer to help with his autobiography. He had chosen Lynn to represent him because she was Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s agent—not unlike his earlier choice of colleges: UCLA, in part because it was Jackie Robinson’s alma mater.

Before our meal was served, a middle-aged woman came up to our booth and, somewhat shyly, asked Rafer for his autograph. I assumed she recognized him as the athlete who, at almost 50, had thrilled the planet by circling the LA Coliseum track, climbing 99 rickety steps, standing like a Greek statue with the Olympic torch held high overhead, and lit the flame to open the 1984 Olympiad as 100,000 spectators roared. He happily obliged.

When the woman looked at the signature, she had an odd look on her face. After she left, Rafer said, “She probably thought I was Sidney Poitier.”

“Or Sammy Davis, Junior,” I said. Davis, of course, was about half Rafer’s size and looked more like a Black Woody Allen than Sidney Poitier.

It was the first time I heard Rafer’s laugh and saw the light of amusement in his eyes. There would be dozens of moments like that in the ensuing years because Rafer was a jokester, and it saddens me deeply to think it will happen again only in my memory.

Rafer heard me laugh over coffee that same day. I’d asked him what he most wanted to convey in his book. His immediate response was to talk about the importance of family. He told me about his wife, Betsy, his brothers, his late parents, and most of all, his children, Jenny and Josh. The saddest he’d ever been, he said, was the day that Jenny, the oldest, left home for college.

I asked where she’d gone to school. “UCLA,” he said.

I cracked up. The Johnsons lived in Sherman Oaks, 15 minutes from the UCLA campus. Rafer knew why I was laughing, and he chuckled along with me, but he hadn’t been joking. That’s how important his family was; nothing was even a close second.

At our first working meeting, we each said we had an idea about the book’s structure. They were identical visions: 10 chapters, each representing an event in the decathlon, which was Rafer’s specialty as a gold-medal-winning, record-breaking world champion. We divided his life chronologically into 10 segments, and, without any contrivance, related them to the decathlon events in proper order.

I’ve written or cowritten more than 25 books now, and that was the only time an original chapter outline remained unchanged. It’s also one of the few times a working title ended up on the book cover. Rafer wanted to call it The Best That I Can Be, which was the guiding principle of his life. No other title was considered.

I spent countless hours picking his brain and sorting through dusty boxes of clippings and memorabilia. I scoured old periodicals and spoke to significant people in Rafer’s life, from family members and business associates to well-known figures like John Wooden, Tom Brokaw, and Gloria Steinem.

When someone contradicted something Rafer had said, he would laugh about the tricks memory played and usually deferred. There was never an unpleasant moment. If he didn’t like something I’d written, he’d say, “I wouldn’t say it that way.” The word gentleman was made for men like him.

I learned a great deal from Rafer, not just about his life but what it was like to be UCLA’s first Black student body president and the first Black captain of a U.S. Olympic team; what it was like to carry the expectations of a country that treated people of color as second-class citizens when competing with the Soviet Union’s best at the height of the Cold War; what it was like to be hailed as the World’s Greatest Athlete and have people sneer when you dined out with a white woman.

I also learned about coaches, colleagues, fellow social activists, and pals who always had Rafer’s back, including the Kennedy family with whom he’d grown close when campaigning for his friend Bobby and remained close through the aftermath of the assassination and decades of work with Special Olympics.

Mostly, I learned how one good man can make a lasting mark on the world, inspiring millions and making no enemies. I learned that it’s possible to gracefully balance humility and pride; to champion social justice and yet harbor no malice; to be supremely self-confident and at the same time self-effacing; to abide in a deep faith without ever broadcasting it.

If not for COVID-19, hundreds, perhaps thousands, would show up to memorialize Rafer in LA. He was not only the best that he could be, he represented the best of what any of us can be.

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply