There is a cognitive bias we refer to in the cognitive sciences as Choice Supportive Bias (CSB).

It happens when we make a purchase, and we justify our choice by creating reasons for why we chose A over B, and why B just wasn’t that good.

When this happens in our lives—from why we turn left and don’t turn right, why we chose who to marry, why we’re an atheist, or why we become religious—it is an attempt to avoid regret. This all happens in the premedial orbital cortex—an area of the brain where we connect emotions to decision-making.

CSB is a form of penance that gives us a sense of useful remorse that we learn from—in hindsight. It allows us to sideline a feeling of guilt and make sense of why we didn’t make the decision we’re regretting in real-time. It’s a post-event form of letting us off the hook.

A Safety Mechanism

Think of it like a mental safety mechanism. As a rule of thumb, consider that humans often say to themselves: “I chose this option; therefore, it must have been the better option.”

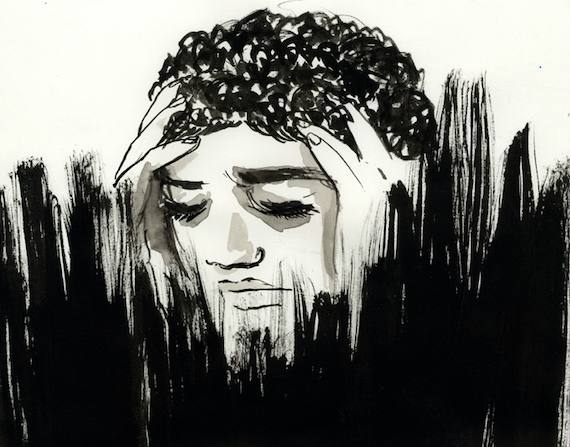

In doing so, it helps reduce regret and generally promotes well-being. Imagine being constantly plagued by doubt over every single decision you ever made. Your ability to make future decisions would most likely be severely impaired, particularly under pressure.

By the way, this is also pretty handy in making us feel pretty successful about decisions that didn’t actually go so well. But, what drives us to do this? It’s connected to how we see ourselves, how we define our values, and how we defend a specific view of our personalities.

We make it fit into a narrative that serves us. We don’t like to fail, make mistakes or allow others to judge us, so, we do our damndest to make sure the image we hold of ourselves is consistent with the actions we believe we need to take.

Choice supportive bias is part of a much larger suite of biases that reinforce the idea that we always make the best decision possible. But, we know this, that just isn’t the case. It’s because we live in a society that has normalized mistakes as wrong and unhelpful to our growth. So, we build a cognitive cosmology that ensures we hide these necessary blemishes from others. It’s called Atelophobia: a fear of getting it wrong.

“As with any phobia, people with atelophobia think about the fear of making a mistake in any way; it makes them avoid doing things because they would rather do nothing than do something and risk a mistake, this is the avoidance.” ~ Dr. Gail Saltz

Choice supportive bias immobilizes us in such a way that we feel confined to the choices we make and the desire to justify them. Rosy retrospection is another bias that attempts to remember past events much better than they actually were. A simple example of this bias at work is historical nationalism, where someone might attempt to remember events in a country’s history in a much more positive light than the events themselves actually were.

When trying to develop new habits, the tendency is to assume that the habit we have adopted is serving us as comprehensively as possible. So, we employ the choice supportive bias that acts more like tunnel vision, keeping us from exploring other possibilities. It makes change uncomfortable and seemingly unnecessary. However, the important thing is to keep an open mind. To invite humility into our decision-making processes, and to create a safe community who will support us and wake us up to our own biases.

Doing these things will ensure that our choices are not working at the same level as our biases.

When the choices are informed by our biases, regret is a natural aftereffect. In fact, the regret is derived from the bias. How so? Because for us to justify the choice we chose (whether it turns out the way we want or not), we have to fill a gap between the choice we didn’t choose and the one we did. That gap acts as cognitive dissonance between choice A or choice B. When we make a decision between two or more objects, we tend to rely on our filtered biases, which act as a form of absolution and we then feel less of a need to justify ourselves.

“….When we recall a past decision, we distort memories to make the choices we made appear to be the best that could be made… As a result, we feel good about ourselves and our choices and have less regret for bad decisions.” ~ from Changing Minds

One way out of such a deadlock is to take time and weigh our options. To seek out advice from those who are not a part of our situations. Another important technique is to be honest to ourselves (and others) when we don’t make a decision that leads to the best-desired outcome. This honesty will also act as a diffusing agent when it comes to feeling regret—mainly because regret wants us to never admit we’re wrong. Admitting we’re wrong and laughing at those decisions that didn’t work out is the posture of some of the best learners in our history.

The temptation is to not embrace humility and become a remorse junkie just so we don’t have to learn, grow, or change. That is the only benefit in developing an obsessive pattern of normalizing remorse into our lives. It keeps us from ever living up to our full potential.

Read 0 comments and reply